In a cultural moment bloated with digital slop, Rossin’s AI-coauthored paintings probe something more unstable and searching

Shifting from her recent cavernous installations, and sprawling digital-heavy interventions, The Totalists, Rachel Rossin’s second solo show in the UK, marks another of her periodic returns to painting. Yet despite this excursion into an ostensibly analogue output, Rossin’s preoccupation with our prosthetic relationship with technology remains consistent. Here, AI is a subject and a coauthoring tool. While the incorporation of technology and (self-)reflection into painting isn’t new (think of the old plein air painters with their Claude glasses, or the camera obscura of the Renaissance), Rossin’s approach feels distinctly symbiotic. Underlying the show is the ‘Scry-Borg’ (the artist’s name, combining scrying and cyborg, for her authored and trained AI). Fed a dataset drawn entirely from Rossin’s own artistic work, beginning with a drawing made when she was five, it generates a stream of perpetually evolving images, which Rossin uses as prompts for painting. One imagines that the works here, in turn, may feed back into the algorithm, continuing the recursive dialogue.

Telos (all works 2025), one of the larger canvases, features a chrome heart encircled by ten tablets, connected via arterial tendrils. Behind it, a washy background offers little resistance to the overt symbolism of the body augmented by tech in the foreground. The result appears almost diagrammatic, lacking the elusiveness and nuance that gives other works here their charge. p(doom)1 and p(doom)2, for example, shine as compositionally freer moments in which the fusion of flesh and machine is less didactic and harder to discern. Across p(doom)1’s surface, metal armatures oscillate through chunks of quickly rendered viscera. p(doom)2 is quieter, more ambiguous, with forms emerging gently in hues of deep blue, violet and red – sketchings that hover and fade, remaining fluid and indeterminate. Brazen Head is a visual outlier: it’s laboured, realistic and largely airbrushed with intriguing layers of tightly enmeshed images – a spinal column leading to an anime head bisected by further metal armatures and so on – but in this more representational state, it feels sealed compared to the porosity found elsewhere.

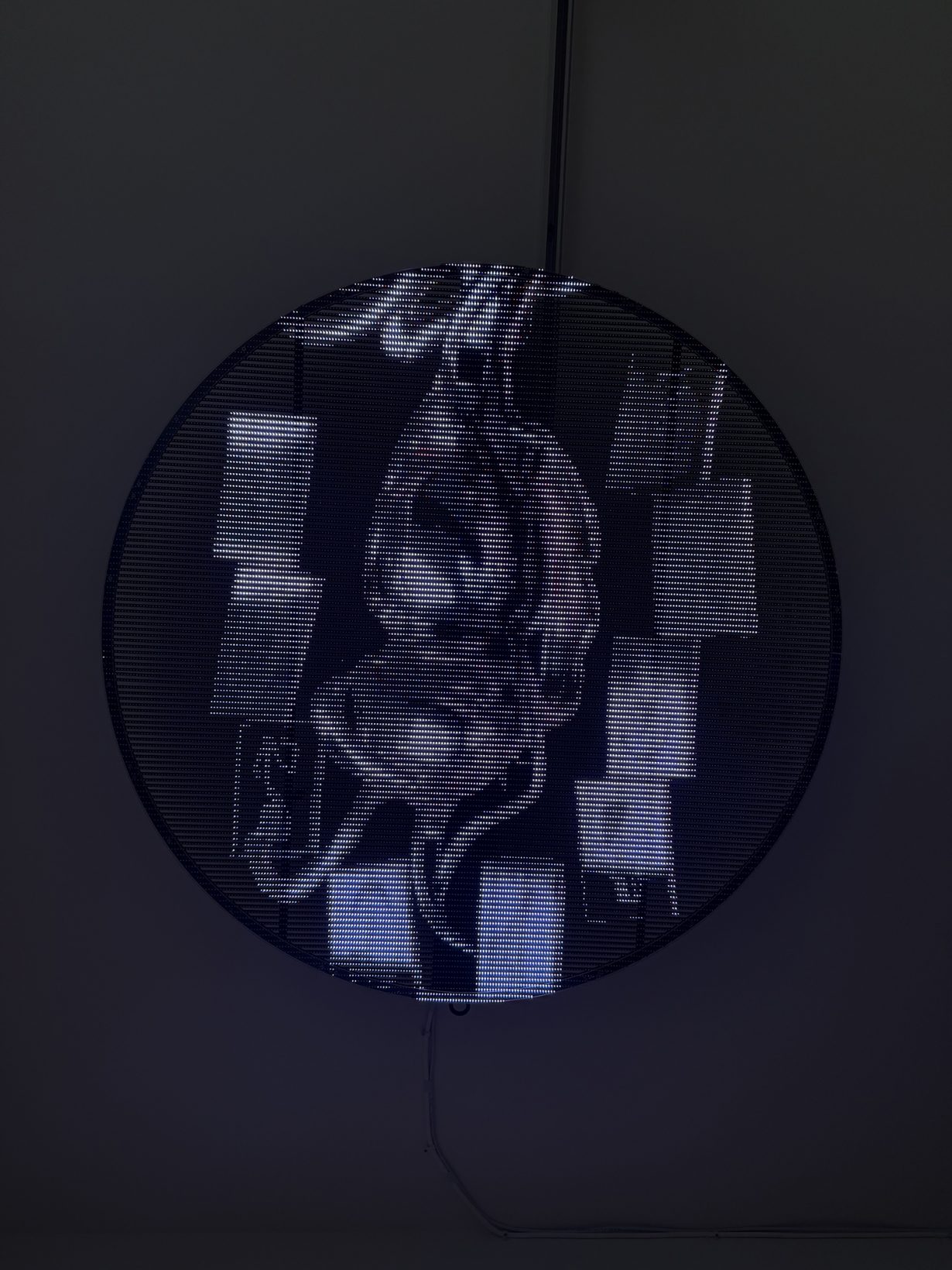

The majority of the canvases, tall and narrow, gesture towards ecclesiastical architecture: stained glass, altarpieces, sacred panels. This reverence is mirrored in the installation of For the Totalists, a ceiling-mounted screen-based work tucked around a corner of the gallery that visitors have to look up to see. It apparently reveals the oleaginous AI forms that are behind the show, in their unmediated state. The screen’s quiet presence echoes the exhibition’s broader conceptual arc: a gesture towards the opacity of advanced technologies and our quasi-religious submission to them. This latent theology frames Rossin’s engagement with the ‘black box’, a term from AI research denoting systems so opaque that even their creators cannot fully explain them.

In a cultural moment bloated with AI slop, Rossin doesn’t mimic the tech’s surface sheen, but co-opts it to probe something more unstable and searching. The results are intentionally unsettled, an attempt to embody what it means to create in a world where cognition is no longer uniquely human. The Totalists asks us to trust in that instability, to believe in the machine, or the artist, as an oracle, even if some works resonate more clearly in concept than in form.

The Totalists at Albion Jeune, London, 24 April – 1 June

From the Summer 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.