Increasingly treated as legal testimony, music functions as a proxy for criminalized Black identity

Last week, following significant and sustained public outcry at the use of rap lyrics as evidence in court, the New York State Senate passed SB S7527, which makes a criminal defendant’s creative or artistic expression categorically inadmissible as evidence against them. Built on the right to freedom of expression, this bill prevents courts from ‘transform[ing] the figurative into fact’ and ‘ignor[ing] the foundational principle that a criminal case should be tried on the facts and not on a person’s ‘propensity’ to commit the crime.’ An attempt to force courts to stick to just the facts, the bill assumes that indexical representations of things that really happened can be clearly distinguished from figurations of fictions, and that there’s an easily defined and recognized difference between, say, news or body cam footage and music videos. SB S7525 clarifies that something like a music video would be admissible as evidence only if prosecutors could establish ‘clear and convincing proof that there is a literal, factual nexus between the creative expression and the facts of the case’.

This amendment marks something of a landmark moment, as rap music faces increasing scrutiny for its use as criminal evidence. In a recent piece in The New York Times, journalist Jaeah Lee and law professor Andrea Dennis discovered that courts find rap lyrics as evidence of criminal activity more often today than they did during the moral panic over gangsta rap in the 1990s: ‘We identified about 50 defendants who were prosecuted using rap between 1990 and 2005, but we found more than double that number in the 15 years that followed.’ Even though hip hop is the preferred musical genre of Americans under 30, no other genre is treated this way: as of 2017, scholars found only one instance where lyrics from a non-rap genre were used as evidence in a US court.

Though Lee and Dennis’s study is limited to the US, the trend of treating rap lyrics as evidence is not: as Dan Hancox reports in a 2019 interview with Skengdo and AM for The Guardian, lyrics from songs in the rap subgenre drill have been used as evidence in British court cases. In 2019 the Crown Prosecution Service claimed that a lyric Tyrell Graham recorded the previous year about putting someone in a coffin was evidence he committed the murder in question because ‘Either they describe the life he already leads or they describe the life he aspires to lead.’ This strategy treats Graham’s lyrics less as a confession of a specific act and more as a supposed indicator that he has the capability to murder someone in cold blood.

By treating rap lyrics as character witness rather than eye witness, British prosecutors attempted to sidestep the thorny issue of whether rap lyrics should be treated like fact or fiction. As music scholars Nicholas Stoia, Kyle Adams and Kevin Drakulich argued in their 2017 paper ‘Rap Lyrics as Evidence: What Can Music Theory Tell Us?’, to treat rap lyrics as testimony, you have to misinterpret rap’s poetic devices as factual reporting. According to Stoia and his co-authors, because of the role improvisatory duelling or ‘battling’ played in the early development of rap music, the genre commonly uses metaphorical violence and fighting to depict the battling rappers’ competition for artistic dominance. When courts hear rap lyrics as evidence of criminal violence, they mistake a metaphor commonly used in the genre for a statement of fact.

However, courts don’t interpret rap lyrics as depictions of factual or fictional events. As Gayatri Spivak notes in ‘Can The Subaltern Speak?’ (1988), Marx distinguishes between two forms of representation: representation as artistic depiction (darstellen) and representation as proxy (vertreten). When rap lyrics are presented as evidence of criminal guilt, courts care less what the words themselves depict and focus primarily on representation as proxy. Citing a study by Adam Dunbar, Charis Kubrin, and Nicholas Scurich that asked people to rate the offensiveness and verisimilitude of rap lyrics versus country lyrics, Jaeah Lee explains that lyrical content matters less than genre label: study subjects ‘judged the lyrics to be more offensive and true to life when told they were rap’. According to scholar Lisa Cacho, criminalization occurs when people are denied the rights and benefits of personhood for who they are, regardless of what they do or don’t do. When taking rap lyrics as evidence of criminal wrongdoing, courts criminalize music for what genre it is, not for what it says.

Courts mis-hear rap lyrics in the same way that attorneys instructed the Rodney King jury to misinterpret the video of him being beaten by police. ‘Rather than assume that filmed facts speak for themselves, these lawyers found in a received stock of already intercepted images of black bodies ready weapons to assault Rodney King,’ which, as philosopher Robert Gooding-Williams argues in Look, A Negro! (2006), framed King ‘in the role of a wild animal and figur[ed] it as a nemesis to civilization.’ The lawyers deflected spectators’ attention away from the visual content of the video of King’s beating (a depiction of a factual event) and towards ‘controlling images’ of Black people’s purported non-humanity.

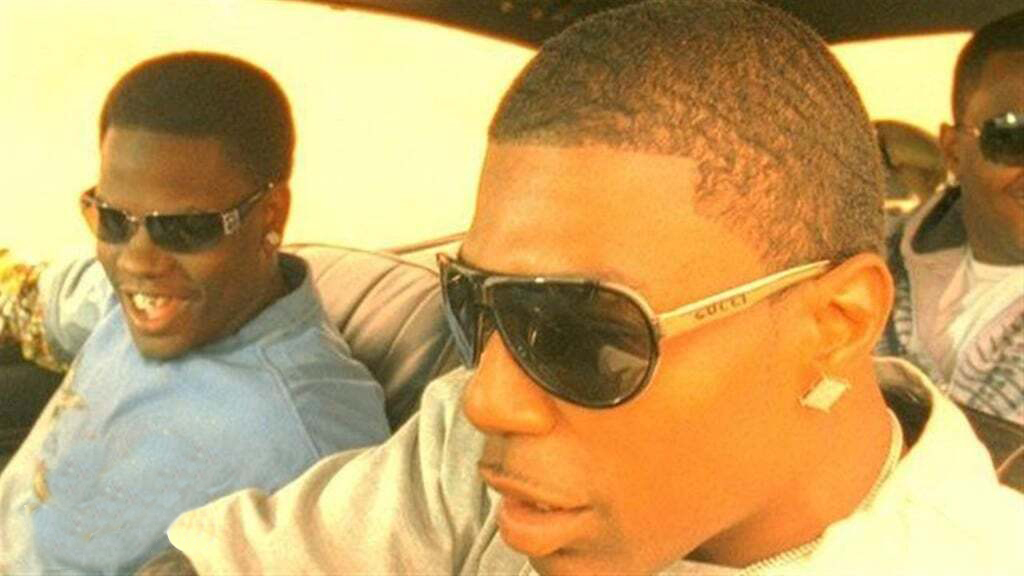

When courts misinterpret representations of Black people, it is not just that they get the facts wrong, but that the epistemic framework they are grounded in is anti-Black. As incorrect as it is to interpret rap lyrics literally as nonfiction, the bigger issue here is the slippage from what those lyrics are believed to depict, to viewing the lyrics as a proxy for a criminalized Black identity. As the video for Shop Boyz’s ‘Party Like A Rockstar’ (2007) cannily clarifies, while white rockstars cultivate the image that they trash hotel rooms and get in drunken fistfights, their behavior is not taken to represent all white people.

Issues surrounding art that depicts violence or ‘obscenity’, to varying degrees of explicitness, defined legally or politically, are by no means new in American courtrooms. When in 1990 the City of Cincinnati charged the Contemporary Arts Center with obscenity for their Robert Mapplethorpe retrospective The Perfect Moment (1988-89), the issue was with what the white queer photographer’s work depicted – gay sex – in an America fearing AIDS and a Republican party warring over arts funding. The Parents Music Resource Center’s ‘Filthy Fifteen’ were primarily white artists like Judas Priest, W.A.S.P., and Twisted Sister singing about sex, drugs, and rock and roll. These white artists were all apparently scrutinized for what their works depicted, but not explicitly for who they were. There has been a shift: courts’ misuse of rap lyrics as evidence is not so much the misinterpretation of fiction as fact, but indicative of a broader white supremacist habit.