From 2019: A recent retrospective of the German artist at Centre Pompidou-Metz doesn’t feel very recent at all

Rebecca Horn’s 1994 installation Kafka Zyklus (Kafka Cycle) consists of three vitrines containing relics of old Europe: a leather suitcase, an umbrella, a pair of shoes, bits of bramble and grass and dried flowers, a feather. Atop the display cases are mechanical books that open and close slightly as if being manipulated by a phantom reader settling into a more comfortable position. Some texts in what might be German, Horn’s native language, are scrawled in Sharpie; from right to left across the glass cases, these become indecipherable scribbles.

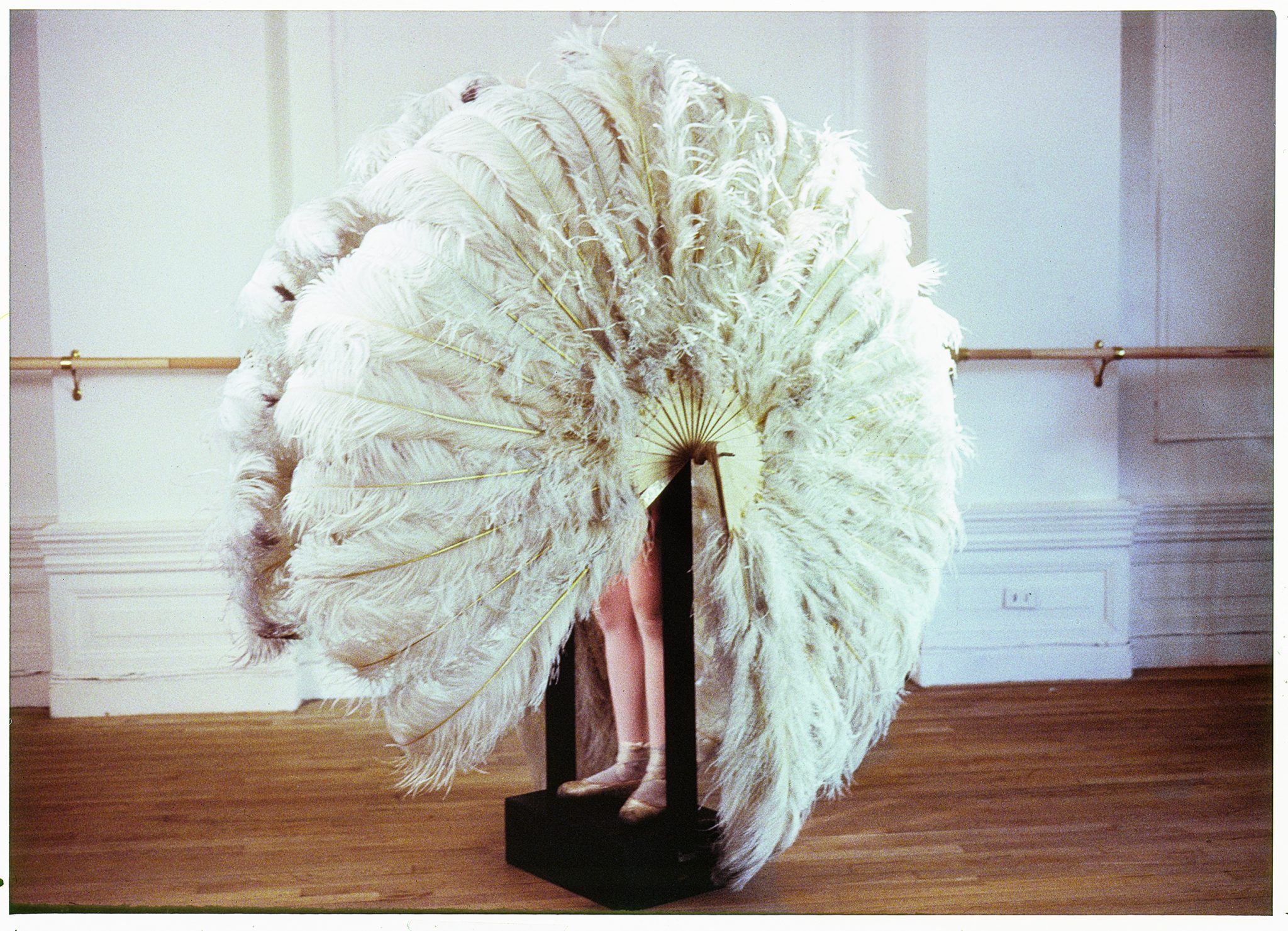

You get a similar feeling from this retrospective as a whole. It begins with a sampling of Horn’s well-known early work: the Berlin Exercises videos (1974–75; a series of nine short films in which the artist explores the relationships between body and space in her studio), the body extensions and the videos that go with them (Einhorn, or Unicorn, 1970–72; Cornucopia [Séance für zwei Brüste], or Cornucopia, Seance for two breasts, 1970), Die sanfte Gefangene (The Feathered Prison Fan, 1978) from Der Eintänzer (The Gigolo, 1978), excerpts from Horn’s films La Ferdinanda (1981) and Buster’s Bedroom (1990). But like the scribbles in Kafka Zyklus, as you read across the exhibit, the further you get into Horn’s career, the less legible it becomes.

Theatre of Metamorphoses is running in parallel to a show of her work called The Body Fantasies at the Museum Tinguely in Basel (5 June – 22 September), which includes some of the other early performance works and Horn’s turn towards kinetic sculpture later in her career. The Metz show, while containing much of the early work for which she is famous, has some glaring holes. Where is the blood circulation machine? Where is Paradise Widow (1975)? Where is the face-pencil mask? The answer, alas, is Basel. And it doesn’t bring us up to date on what Horn has been doing lately: the most recent work is from 2005.

Any gap is plugged instead by surrealist works by Meret Oppenheim, Man Ray and Brâncuși, drawn from public and private collections. The curators’ insistence on these antecedents sometimes grates: Horn’s work doesn’t need that kind of scaffolding to be understood. Occasionally it’s useful, as with the section that traces her interest in the bounded body to dadaist and surrealist poetry and illustrations. Oppenheim, whose powderblue gloves with veins drawn on the back (Handschuhe [Paar], 1985) are juxtaposed with Horn’s Fingerhandschuhe (Finger Gloves, 1972), might appear especially important given she was Horn’s mentor; though in this case, considering that Oppenheim’s gloves came late, the influence goes in the other direction. (Of course, Oppenheim made work with gloves well before Horn, but these are not in the Metz show.) Other connections are more tenuous. Glad as I was to see Claude Cahun’s Autoportrait comme Elle dans Barbe-Bleue (1929), there’s no way that photograph was an ‘influence’ on Horn, who was already an established artist by the time Cahun’s work was rediscovered during the 1980s and became widely shown during the 1990s.

So Theatre of Metamorphoses feels like a thesis show reading Horn through Surrealism. But for those less familiar with her work, it’s asking them to imagine a narrative on the basis of a few provocative, brilliant fragments. And then it’s asking them to travel to Switzerland to get the rest of the story.