A critic questions framing the American as an artist for all times

Mike Kelley’s career can be divided, in retrospect, into three sections: the part most people didn’t understand or even know about (the late 1970s through to the mid-80s), the part where the work tightened up and yet got misread (beginning during the late 80s) and the American artist’s reaction to these earlier periods, which led to everything that came after (from the mid-1990s to 2012, the year he died). The lesson learned along the way is that ‘Mike Kelley’ was, to some degree, whoever the audience and the cultural moment wanted him to be. With the American artist’s touring survey Ghost and Spirit – now at London’s Tate Modern – this point is particularly felt. We’ll get to how. But first, let’s back up.

A working-class lapsed Catholic from Michigan with, it appeared, a mile-wide antiauthoritarian streak, Kelley (born in 1954) spent his early creative years making installations and performances that leaned into conceptual and physical sprawl while valorising whatever was then quietly marginalised, unwelcome and repressed in contemporary art – whether craft aesthetics, occultism and uncanniness, irrationality, low cultural references or adolescent behaviour. An instructive piece of juvenilia in the present retrospective, at least as seen in its previous iteration at Düsseldorf’s K21, is The Futurist Ballet (1973): video documentation of a work made while Kelley was a first-year student at the University of Michigan. This ‘reenacts’ and tricks out with counter cultural sexual babble (eg about a female performer’s successful stripping career), a 1917 work by futurist Fortunato Depero only known about through scant photographic documentation.

In 1978 Kelley would graduate from Los Angeles conceptualist hothouse CalArts having constructed handmade birdboxes based on church architecture. A year later, the multi-part photo/text/drawing sequence The Poltergeist featured photos of him trailing ectoplasm from his nostrils, and writings that bundled together uncontainable adolescent and super-oracular, mediumistic cadences. The multipart natural energies in multimedia project Monkey Island (1982–83) began with a diagram that purported to explain the world and spun off deliriously into a room-size installation of drawings, writings, sculpture and performance suffused with erotic and nautical themes (drawings of giant-assed monkeys, handwritten texts speaking of ‘mount[ing] the island’, anthropomorphic bells having sex). A throughline in the above works, and Kelley’s work in this era per se, is a generalised questioning of what can be known about reality and of those who would purport to know, Kelley steadily reducing epistemological questions to absurdity.

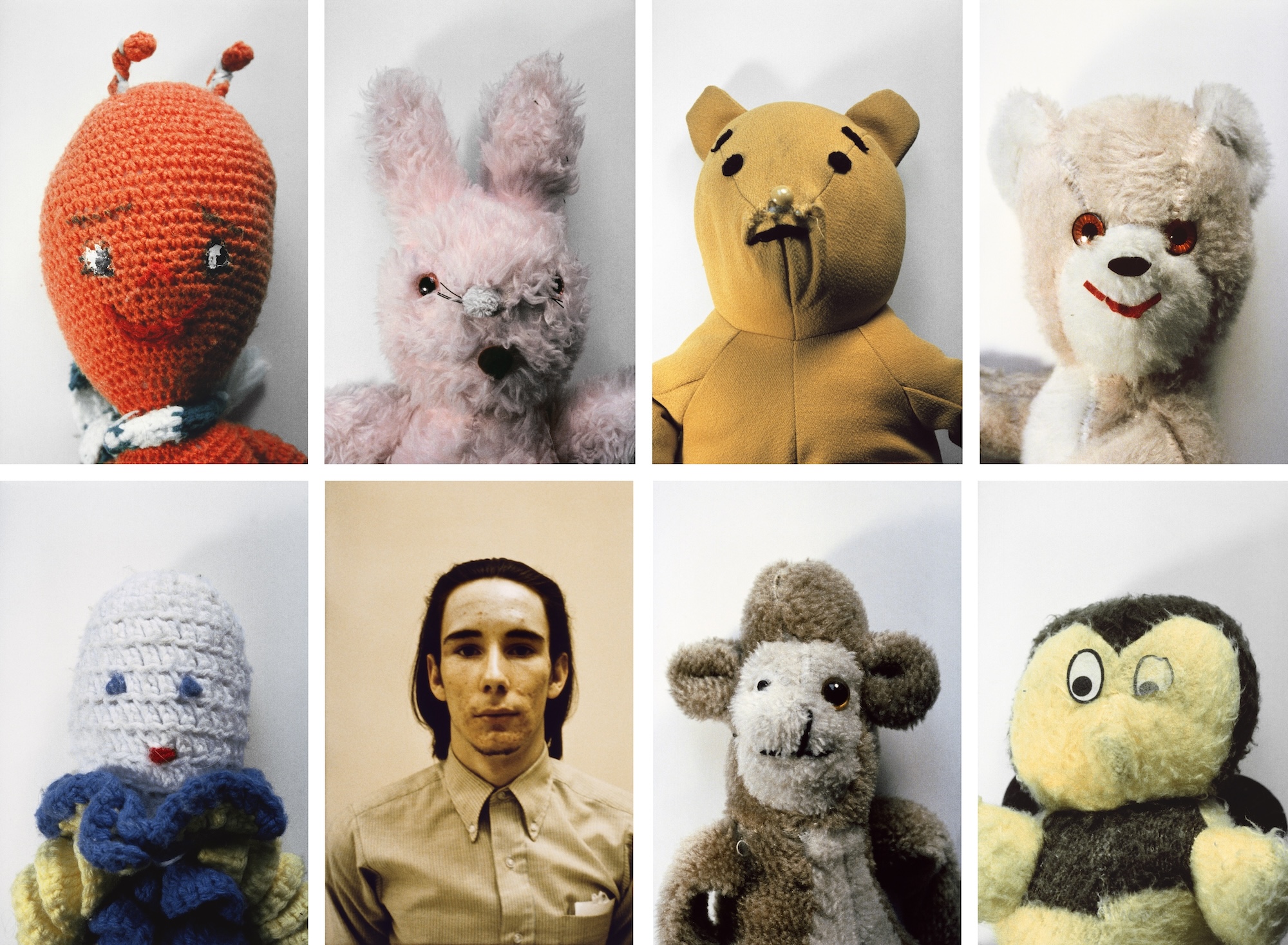

A few years later, though – as the retrospective’s timeline lays out – and particularly as the artworld’s attention swung towards Los Angeles, Kelley made a breakthrough in terms of profile with the series of discrete works and installations that he collectively titled Half a Man (1987–91), a newly punchy and focused visual language of used, soiled and thrifted stuffed toys and stitched text banners: eg ‘Pants Shitter & Proud / P.S. Jerk-Off Too (And I Wear Glasses)’ in 1987’s Three Point Program / Four Eyes. These fabric-centric works continued to establish his interest in what the artworld disdained, from female-coded stylistics to the unstable energies of immaturity. Take 1987’s landmark More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid, first shown at Rosamund Felsen Gallery in Los Angeles in that year. A wall-hanging assemblage of stitched-together, often handmade teddies and gonks – one that also reads, if you squint, as an infantilised take on colourful abstract painting – it sets up discomfiting psychodynamics concerning other invisible power relations: specifically, between parents and children. Yet the feedback that Kelley got, particularly concerning the overfondled dirty toys and general vibe of abjection, suggested that audiences thought the work was simpler than that, and that its linkage of childhood and abjection pointed directly at child abuse – the artist’s own. This was a hinge point.

More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid and The Wages of Sin, 1987 © Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts, Los Angeles. All Rights Reserved / VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2024

“So”, Kelley recalled in 2005 during an interview for a PBS documentary series, “I said, ‘well, that’s really interesting. I have to go with that. I have to make all my work about my abuse – and not only that, but about everybody’s abuse. Like, that this is our shared culture.’ This is the presumption, that all motivation is based on some kind of repressed trauma.” (This aligned with, though didn’t necessarily espouse, Repressed Memory Syndrome, a concept traceable back to Freud, popular during the 1990s, and largely debunked since.) Kelley’s work thereafter steered into memory, forgetting and the mutable definition of truth that might be occasioned by a materialisation of false remembering.

This narrative is what structures the second half of Ghost and Spirit. For Educational Complex (1995) he built a table-top architectural model that hybridised all the schools he’d ever been to, not only including the parts he could remember about this early site of institutional control and inculcation, but also rendering as ominous blank blocks the parts he couldn’t. The sprawling, multimedia, apparently uncompleted series Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstructions (2000–11) was intended to generate 365 videos; it spun off into discrete, but already unwieldy projects like Day Is Done – excerpted in Ghost and Spirit – his 2005 Gagosian exhibition of sculptural/video ‘islands’ between which the viewer channel-surfed, as it were. Here Kelley aimed to fill in the gaps in his memories of schooling in a way that technically wasn’t true, but in a way was. The films and photos in it are based on found high school yearbook photos of what he termed ‘folk performances’ – ‘Religious Performances, Thugs, Dance, Hick and Hillbilly, Halloween and Goth, Satanic, Mimes, and Equestrian Events’ were his categories for Day Is Done – suffused with a creepy sense of reenacting the repressed, probing psychic wounds. ‘I wanted’, Kelley said of this show to Artforum in 2005, ‘to create a contemporary gesamtkunstwerk that is not utopian in nature but is an extension of our current victim culture.’

Read from the perspective of the present, this is interesting territory. It might, at the time, have appeared to be in conversation with Robert Hughes’s widely read broadside against political correctness, Culture of Complaint (1993), which essentially analysed America as a culture of self-pitying whiners enabled both by conservatism and liberal academia. In suggesting that the US had become a nation of grievance mongers (and using a title, repurposed from a song by doomed folkie Nick Drake, that implies a downward slide), Day Is Done could be considered as anticipatory, and diagnostic, of that more fervent and visible sense of white grievance and perceived victimhood that has gripped the US in the past decade particularly, with the results that we’re all aware of. Or it might, to some, sound implicitly delegitimising of genuine grievance.

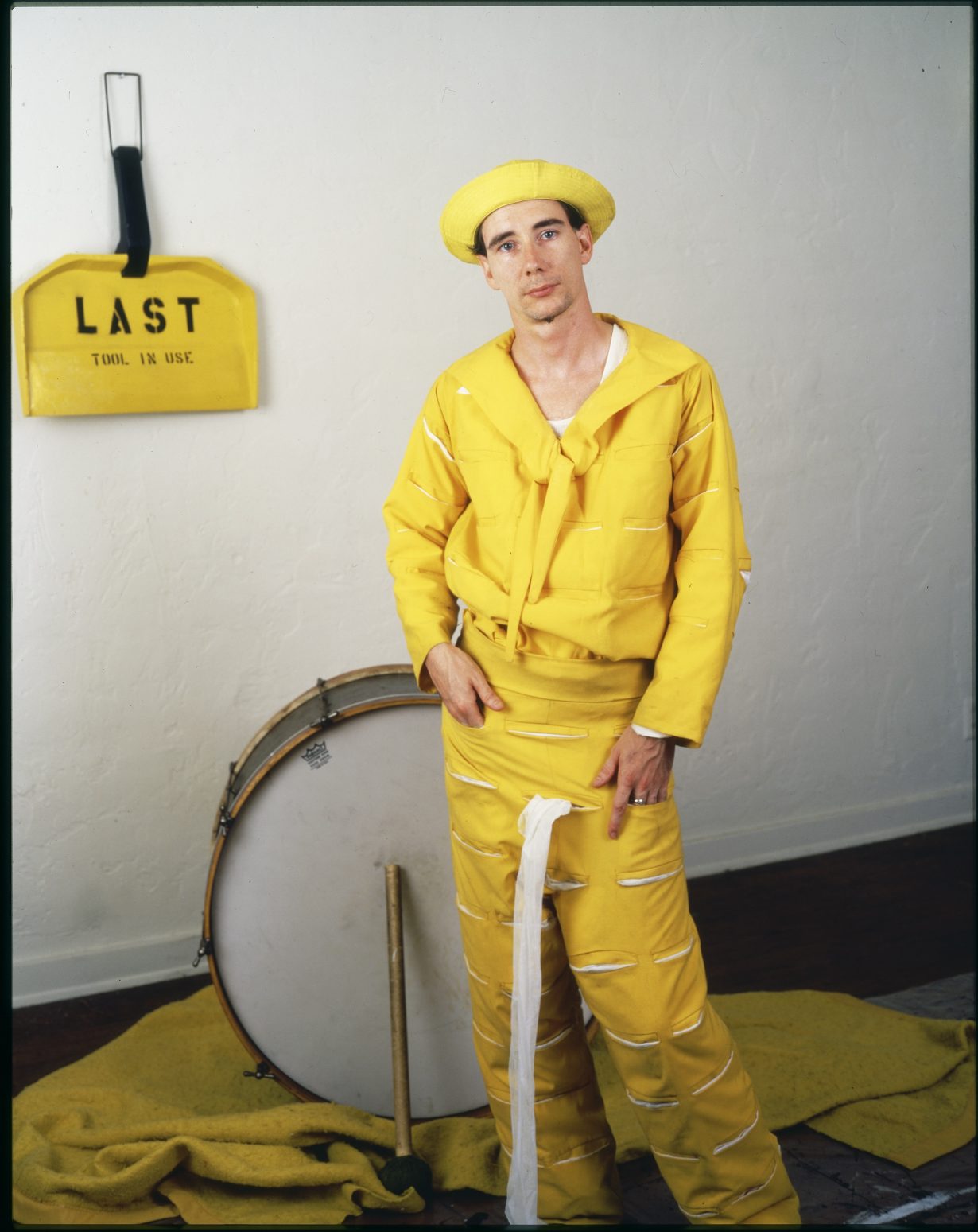

In any case, perhaps mindful of the latter, this is not where the essayists in the catalogue for Ghost and Spirit choose to place their emphasis, instead building a context for Kelley that figures him, in various ways and however he might have felt about it, as something of a multidirectional ally. Artist Cauleen Smith’s text, which analyses an early performance/video work, is titled ‘On Mike Kelley, The Banana Man, and the Refusal to Accept the Invisibility of Whiteness’, and sees the artist in his banana-coloured suit as ‘refusing to accept the privileges of the way whiteness functions as an invisible force and enclosure’. A transcribed conversation between artist Suzanne Lacy and curator Glenn Phillips probes, evenhandedly, Kelley’s relation to feminism. In her synoptic essay, exhibition cocurator Catherine Wood notes his interest in queer cinema and drag, suggests that his gaming with identity anticipates how the postinternet generation experiences selfhood and finds resonances between his practice and younger artists like Cally Spooner, Pamela Rosenkranz and Mire Lee. Mark Leckey, a later adept of intermingled video and sculpture, hymns him. The spiritualist aspects of Kelley’s work are pretty au courant too, and artist Grace Ndiritu – whose work has been founded on a questioning and respiritualising of art institutions – contributes ‘Grief: A Love Letter to Mike’. All of this serves to situate him in a shifting present. It’s also a reminder that a practice as profuse and many-angled as was Kelley’s (the abovementioned works barely scratch its patchwork surface) can, as Andy Warhol’s proved, be made without much distortion to speak to successive eras.

The last show of his that I saw during his lifetime was Exploded Fortress of Solitude at Gagosian, London, in late 2011. It expanded on and reframed Kelley’s major series, the Kandors (1999–2011): sculptural renderings in varicoloured resin of Superman’s birth city, Kandor, shrunk and placed under a preserving bell jar – images of which in his Fortress of Solitude were rendered variously, like an unstable or half inaccessible memory, in comic books over the years. The Kandors, particularly in light of Kelley’s diagnostics of American decline, are multivalent and ambiguous, an attempt to preserve something from Superman’s past, or that of the US, that is inaccessible, reduced, not necessarily true. At the gallery, myriad high-tech iterations of them glowed in multicolour amid a catacomb of big blackened sculptures suggesting Superman’s ice-ringed stronghold as a blown-apart ruin. This, along with the associations offered by the bell jars – see Kelley’s 1999 video Superman Recites Selections from ‘The Bell Jar’ and Other Works By Sylvia Plath – would take on a grim resonance a few months after the show opened, upon Kelley’s death at age fifty-seven, apparently by his own hand. But at the time, this presentation, with its myriad expensive variations on two sculptural formats, primarily felt like a once-unbridled artist reduced to glitzy variations, serving up dismayingly high-production-value product for a megagallery’s clientele: a fate – again, becoming who others want you to be – that has befallen many an inventive creator since; Kelley, bleakly, got there early.

Though there are Kandors in Ghost and Spirit, the ruins, and this moment, are excluded, a part of the past that it can’t quite or doesn’t want to remember. Instead, the exhibition sedulously retools Kelley for our time: for emphases on identity and spirituality, for the present near-orthodoxy of video-infused postmedium art practice. Kelley’s practice, it’s clear, is sufficiently spacious and sprawling, even fundamentally unmanageable in its totality, to allow it. In years to come, he’ll surely return from the beyond again, and anew.

Mike Kelley: Ghost and Spirit is on view at Tate Modern, London, 3 October – 9 March