Cybernetic prostheses meet art history, cartoon physics and the acid-woozy ruins of 1960s counterculture in Mochu’s cinematic universe. The Indian artist’s output spans multiple media, but he is best understood as a writer with a movie camera. Text overflows his films like water from an infinity pool, taking shape as accompanying essays and lecture performances. Like the works of Soviet film-director Dziga Vertov, his videos eschew straightforward narrative exposition for a kind of database cinema of accumulated fragments and a liberal use of special effects. And although nearly a century of technological development separates them, both filmmakers evince an interest in modes of perception and transhumanist utopianism. But whereas Vertov understood the camera lens as a second eye, in Mochu’s hands it becomes something groovier and weirder, tapping into transhistorical astral planes to function more like a third one.

Mochu was born in Kerala, grew up around India and is currently based between Delhi and Istanbul. He is wary of the identitarian pitfalls that await non-Western artists, and uses this childhood nickname over his legal one for the opacity it grants, explaining over email that “I like the lazy ambiguity it affords (gender, species, ethnicity, collective/individual), nothing is clear in it.” He studied animation and communication design at Delhi’s National Institute of Design during the early 2000s, a time when celluloid was being discontinued and the industry was moving towards nonlinear digital editing. Mochu arrived at experimental cinema via a process of elimination – “I wasn’t interested in ads,” he explains over Skype – and never formally trained as an artist. Later stints at the now-defunct Sarai Institute, set up by Raqs Media Collective in Delhi, and Ashkal Alwan’s Homeworks Program in Beirut further honed his interest in critical theory (Chris Kraus, Kodwo Eshun, Reza Negarestani, Jalal Toufic) and technology.

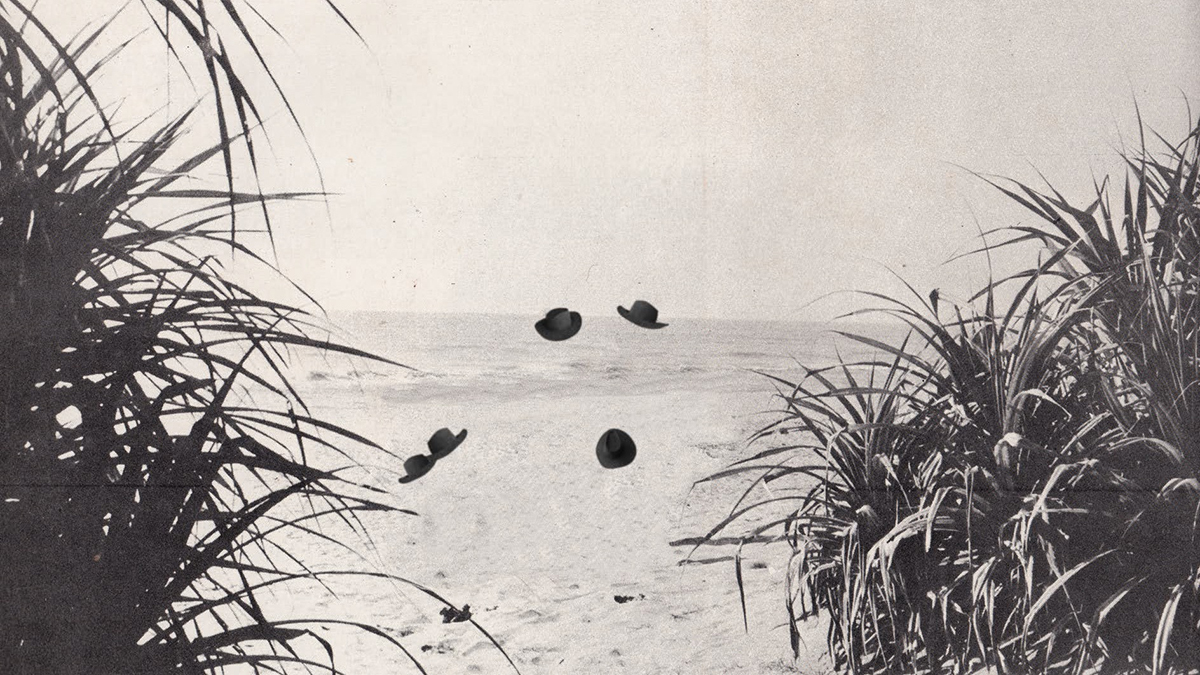

Nevertheless, he grew up around art: his father was a painter, and the family spent some time at the Cholamandal Artists’ Village on the outskirts of Chennai. It was India’s largest artist colony and the birthplace of the Madras Movement of Art, which differs from the better-known vanguardists of Indian modernism, the Bombay Progressives, for its utter rejection of European masters in favour of local art movements and indigenous craft forms. Decades later, in 2015, Mochu would make A Gathering at the Carnival Shop, about one of the artists at Cholamandal. The film orbits the curious 1973 disappearance of enigmatic outsider artist K. Ramanujam – who, according to the film, may have turned into a black dog or a hat – but is equally a portrait of place. It eschews documentary conventions for a conversational, exploratory tone that lingers on archival images, artwork and Ramanujam’s fellow artists, now old men, who reminisce at unedited length.

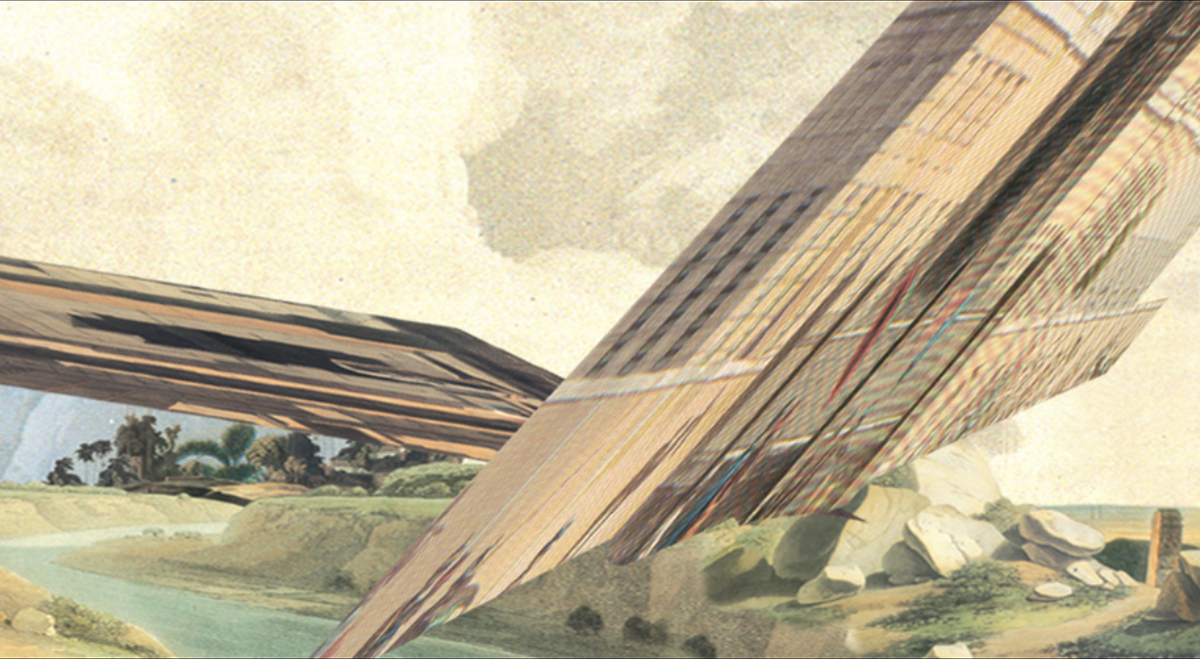

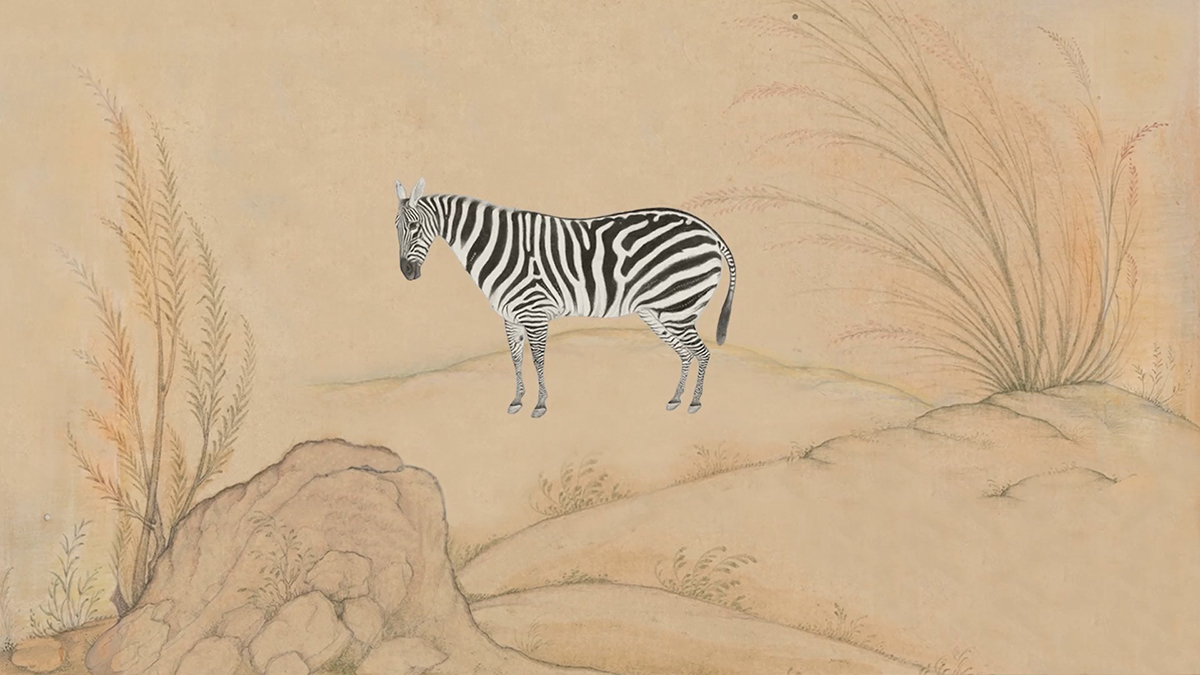

There is a sense throughout Mochu’s practice that art history unfolds from topography. An early short video, Painted Diagram of a Future Voyage (Who Believes the Lens?) (2013), posits a speculative Indian landscape derived from aquatints produced by colonial painters Thomas and William Daniells. Here, buildings are picked up, distorted as if they’ve taken a timespace-shearing lap around the galaxy – anamorphosis is reframed as the distorted gaze of Empire – to create a sci-fi alien landscape that is as unmoored from reality as the Daniellses’ Orientalist fantasies. Another short, Mercury (2016), similarly intervenes in an art-historical landscape through cut-and-paste, zinelike animation, this time the Mughal court painter Ustad Mansur’s miniatures featuring plants and animals.

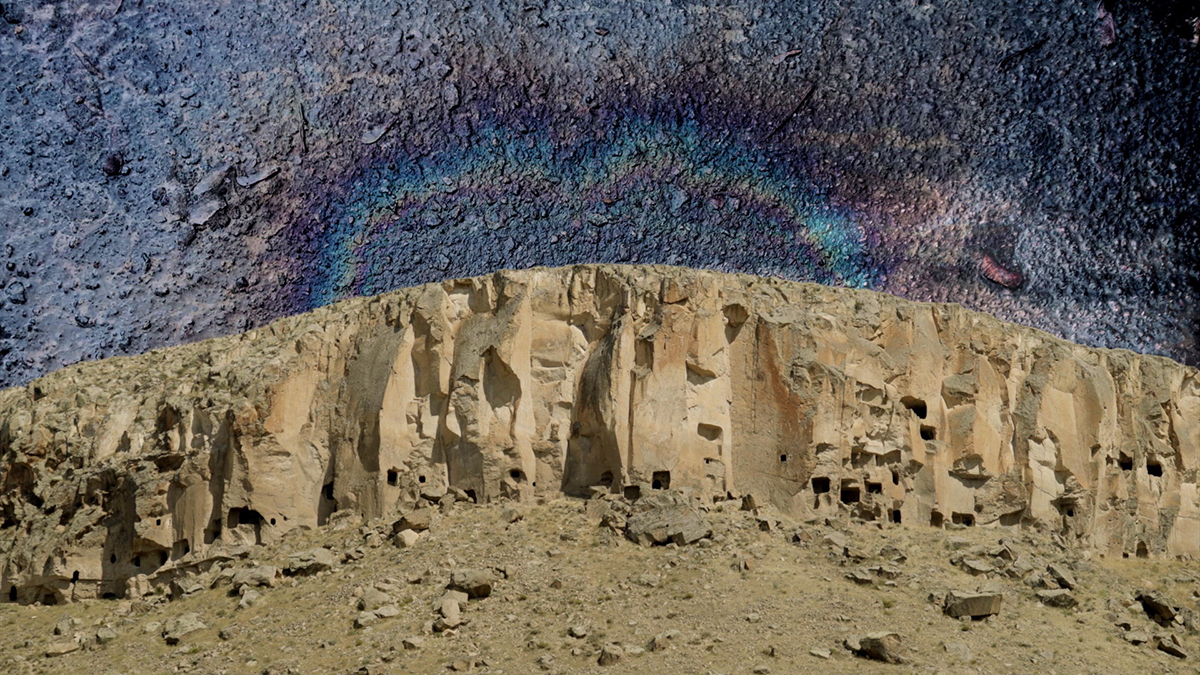

More recently, Mochu has been thinking about the way in which freeports and financial speculation alter flows of linear time – art futures, instead of art history – by locking down the future, much as an art museum safeguards the past. He is adapting a 2018 lecture-performance on the subject into a book, which will be copublished by Reliable Copy and the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art. Another lecture performance, Toy Volcano, whose presentation was postponed by Lebanon’s 2019 October Revolution backing into the pandemic, considers the deep time of geology – and Anthropocenic change as special effects – via Japanese manga, trypophobia and two bizarre, thoroughly enjoyable tales.

Mochu’s early influences come from the Indian experimental cinema tradition, and include Amit Dutta and Kamal Swaroop, both of whom he credits with expanding his sense of what was possible as a student. As for Vertov, Mochu cites the Soviet filmmaker’s contemporaries Georges Méliès, Segundo de Chomón and later Dadaist and Surrealist collage films as stronger influences, as well as Chris Marker and certain essay films from Orson Welles, David Blair and Jean-Luc Godard, which extend the Vertovian tradition and, “while sustaining a documentary layer, also employ a heavy layer of trick imagery and effects”. He is also particularly drawn to science fiction, such as work by the Russian authors Arkady and Boris Strugatsky and the Polish Stanisław Lem, which he finds beautiful in their abstraction, noting that the genre was widely available (in translation from Russian) in the children’s section of Marxist bookstores. “There’s an ontological confusion about things, and you don’t know whether a thing is an object or a person. This kind of fundamental confusion I think is very well done in the Eastern European context more than in the American or French,” he says. This ontological confusion equally pervades Mochu’s practice, as in the example of Ramanujam, the artist who became a black dog and/or a hat.

It’s an interesting point: technological development tends to be so bound up with narratives of the nation that a country’s sci-fi inevitably reflects its national mythologies even as it might be critical of them. Consider the individualist, techno-utopian impulses of American science fiction, for example, which does nothing so much as recast Manifest Destiny for space exploration. In contrast, Mochu points to the existential dread that pervades Soviet novels as well as their particular literary devices created to circumvent the restrictions imposed on those writing from behind the Iron Curtain. Given the unprecedented crackdowns on personal and press freedoms happening in India today, from cutting broadcast media and jailing journalists who publish stories critical of the ruling party, to the ongoing epidemic of caste-based sexual violence, I wonder whether more Indian artists might not find Soviet science fiction instructive.

At the same time, Mochu is careful to describe his own work as technofiction, explaining that “most of my works are dealing with technology rather than science: technical device, some philosophy of technology, however badly misunderstood that might be, and technoscientific imaginaries”. He is perplexed to find little in the way of a native philosophy of technology in India beyond the kind of gurus-and-jugaad spiritual-meets-technopreneurial schlock you might spot at airport bookshops the world over. He cites Yuk Hui’s recent work on China as an exemplary analogue here, and at one level his practice might be understood as a journey to figure out what that might look like. The California Ideology may have lost its sheen as efforts are made to hold Big Tech accountable for their misuse of consumer data and its lax monitoring of political ads and disinformation, but it is alive and well in IT hubs like Bangalore and ‘Cyberabad’, and in the ethos of the Indian Century. Mochu is currently working on a film about Hindu fundamentalists and their successful takeup of ‘Dark Enlightenment’ (a neoreactionary movement founded by Nick Land and Curtis Yarvin) alt-right tactics to manipulate public sentiments.

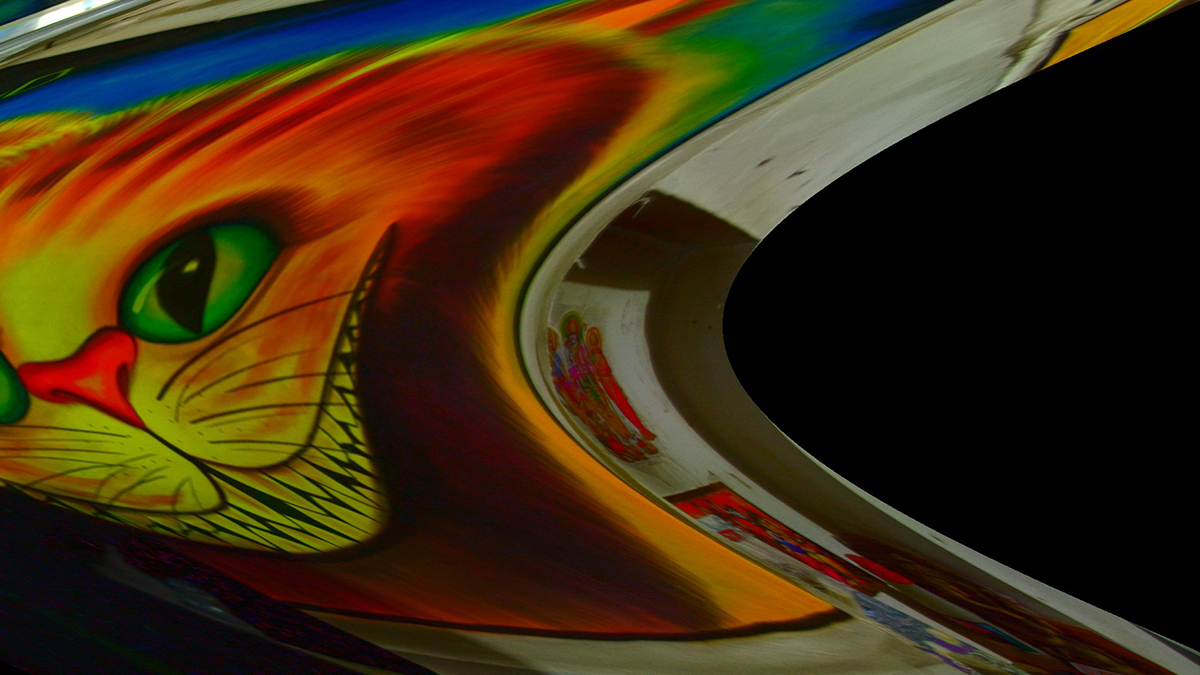

Of course, the exchange goes both ways. “In India we’ve been peddling and selling spiritualism for centuries,” the artist remarks. Cool Memories of Remote Gods (2017) is a kaleidoscopic nocturnal trip, the kind where you’re not sure what exactly you’ve ingested, dissecting the corpse of the 1960s hippie trail to trace the linkages between its appropriations of suitably ancient Indian mysticism and the development of the personal computer. Mochu was careful to emphasise spirituality over religion here, deciding not to film in Varanasi for this reason and instead choosing the tiny-but-sacred (to both Hindus and Sikhs) remote desert city of Pushkar. Drugs, intimated via heavy manipulation, are compared to personal technologies – or is it vice versa? – even as old posters, psychedelic paraphernalia and the generalised abjection of the ageing hippie signal the movement’s bankruptcy. Commissioned for the 2017 Sharjah Biennial, it was first shown in a darkened room in a building shaped like a flying saucer; I didn’t quite have my own spiritual epiphany, but it was perfect.

Rahel Aima is a critic based in New York

All images: Courtesy the artist