There is a painting in Charles Garabedian’s exhibition titled Beauty (2013). It is one of the ugliest works in the show. And it has some stiff competition: Blue Lipstick (2013), for instance, portrays the cyanotic features of a person of indeterminate gender who appears to have been recently chewing on an ink cartridge. Giotto’s Tree (2012) shows an ungainly woman with big legs and no arms (literally – no arms!) entangled in the branches of a sapling.

Beauty, however, takes the biscuit: a panoramic length of paper (actually six sheets conjoined) within which a naked pink figure is trapped as if in a sealed coffin. His/her torso is dramatically elongated, and his/her legs are folded uncomfortably under his/her belly. Much attention has been paid to the knobby forms of the knees, which command the centre of the picture. Likewise the wrinkled skin of the wrists. The person’s gaze is fixed on a point offscreen, while a weak smile plays on the lips.

It is a captivating image. Since Garabedian began painting in his early thirties, the Los Angeles-based artist has ploughed a determinedly idiosyncratic furrow, never adhering to contemporary fashions (though he was included in Marcia Tucker’s 1978 ‘Bad’ Painting exhibition at the New Museum, New York) nor to received conceptions of balance, taste or beauty. He is now eighty-nine, and as prolific and restless as ever.

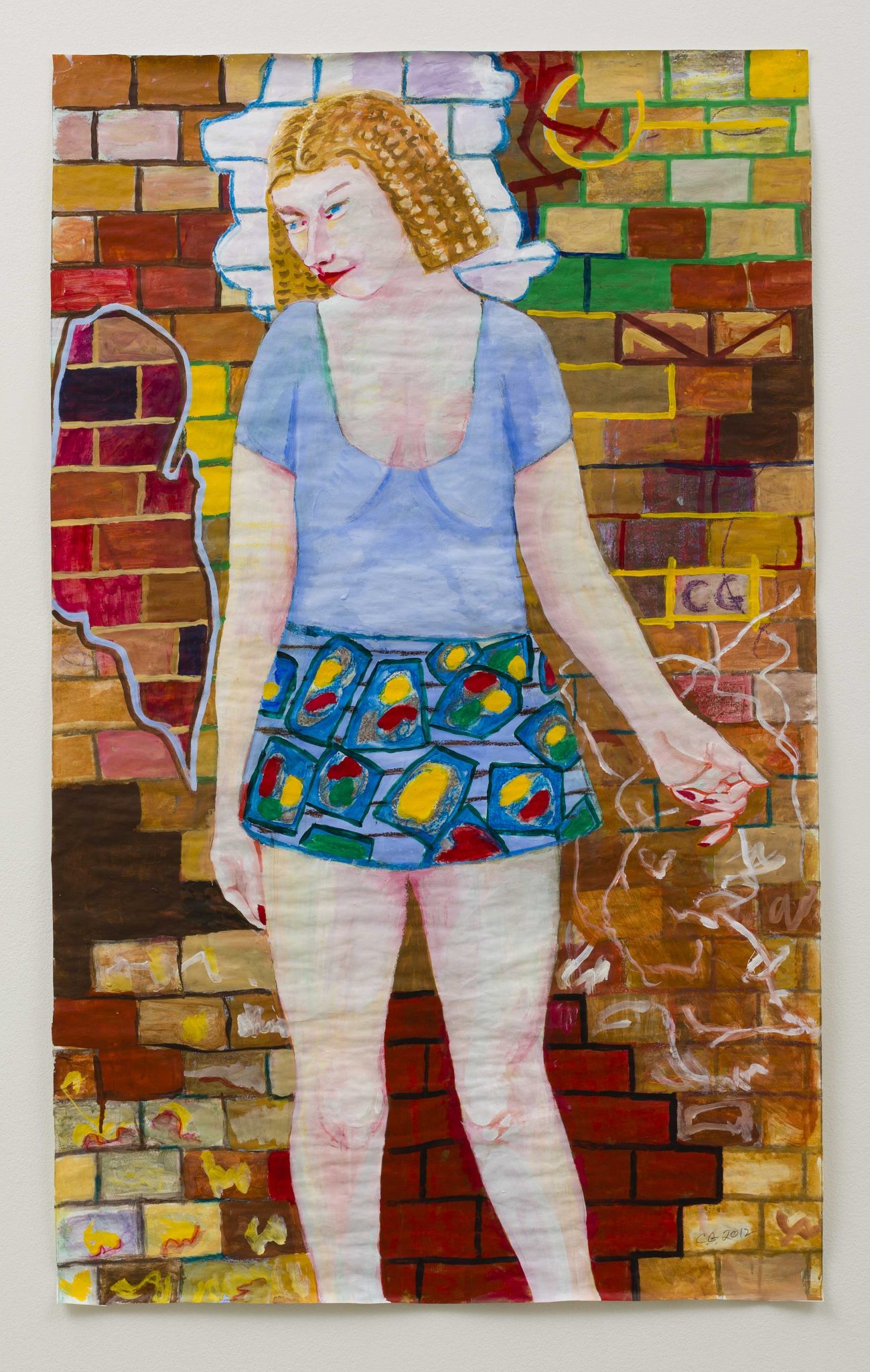

This selection of works on paper is titled, clunkily, re:GENERATION (the artist reportedly has a friend come up with titles on his behalf ). But regenerate Garabedian does. Among those on show are pictures that clothe the artist’s typically nude subjects in patterned garments and improbably coloured hair. In others, dynamic, vibrant backgrounds do their utmost to distract the viewer’s attention from the ostensible subject. In Full Frontal (2012), for instance, a pattern of fish and ocean waves threatens to swallow the figure of the woman in front, who is herself half- hidden behind the floral design that explodes from her dress. The only face we see is inscribed on that dress, at belly height.

There is much in Garabedian’s paintings that does not add up. Incomprehension, indeed, might be said to be one of the artist’s muses. That, and beauty; between them they signify a prize ever tantalisingly out of reach. Two tall vertical paintings take the story of Salome as their subject. It does not matter whether you know the details of the myth (why does each image contain a hole in the ground?) nor that here Salome, that icon of erotic desire, is not much to look at. It is enough just to lose oneself in the artist’s use of line, in gorgeous pools of deep and subtle colour. Beauty, in Garabedian’s work, exists in the thrill of visual storytelling at its most unpredictable, and in stumbling into unexpected moments of clarity along the way.

This article was first published in the Summer 2013 issue.