Joe Goode has long made pictures designed to be looked through, not at. His work is deadpan, and seemingly innocuous. The LA Times critic William Wilson, in 1971, called it ‘neutrality-style art’. Perhaps this mildness is why he never got quite as much attention as his childhood friend Ed Ruscha, who also does deadpan but who usually cuts his neutrality with non-sequiturs (often verbal) that are arresting and funny. Goode only trades in the very lightest of humorous touches – a milk bottle painted mauve, for instance, placed on a shelf in front of a mauve monochrome canvas. That was his early Milk Bottle series, (1961-2), still amongst his best-known work.

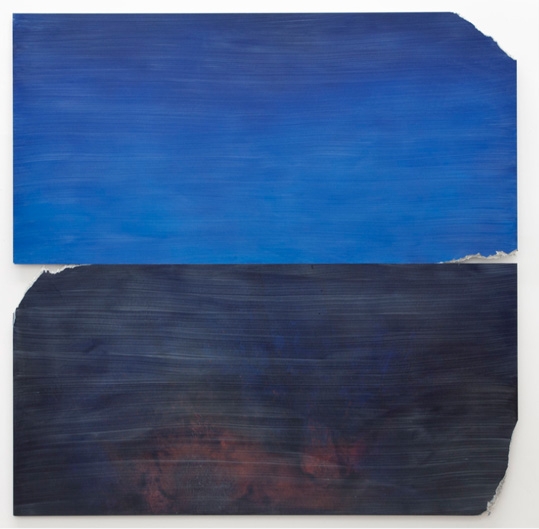

Now in his seventies, the Los Angeles-based artist continues to experiment and refine. He has filled Michael Kohn’s spacious new gallery on Highland Avenue with apparent ease, showing off a new series of seascapes made on large fibreglass panels. Most of these paintings are only cursorily representational: they typically consist of one horizontal four-by-eight foot panel, painted dark blue, beneath another horizontal panel painted a lighter blue. The seam where the two rectangles meet is the dead level horizon.

Even the simplest paintings here achieve in their brushed surfaces infinite degrees of nuance and depth

Not so fast. Behind the poker-face, Goode is a deft and sensuous painter. Even the simplest paintings here – So Still, for example, or Sail Away (both 2013) – achieve in their brushed surfaces infinite degrees of nuance and depth (their Ikea-bland titles are decoys, I would like to believe). On sustained inspection, Goode’s palette goes far beyond shades of blue. The sky in Sail Away is a lightless grey; in Cruising (2013) soft clouds of dusty pink pile up on the horizon. The best paintings here, like the sublime Know Means No (2013) and the extraordinary, infernal, Honk If You See Jesus (2014), are the ones that stray furthest from the programmatic simplicity of Goode’s template.

In any case, these paintings really aren’t about sea and sky. They are about their ontological status as objects that attempt – and fail – to capture a particular archetype of pristine natural perfection. We know this because Goode has taken a grinder to the sides of the fibreglass panels, cutting off corners and gouging into horizons. These torn edges reveal a honeycomb mesh inside the fibreglass; this too represents a kind of perfection, in contrast to which the painted surfaces seem weathered and dirty. In past works, as with the Torn Sky and Torn Cloud series (1969–76), Goode slashed canvases that he’d painted and then mounted the wreckage over another canvas support. A selection of charcoal drawings in this show, from 1977, consists of dark clouds on paper that has subsequently been scratched and gouged.

Goode titled the exhibition Flat Screen Nature. In places, the texture of the honeycomb panels gives the paint a pixelated effect, which apparently reminded the artist of a computer or television screen. (Again, surfaces to be looked through.) But this contemporary technological twist seems less germane than the works’ relationship to the divergent histories of landscape and non-representational monochrome painting. After all, how relevant, really, is pixilation to digital experience in the era of Retina screens and HD?

Goode is at his best when he keeps it analogue. In a side gallery, several charcoal drawings from his X-ray series (1976) depict sheets of tattered white paper apparently taped against a dark background. Goode’s method was to tape one piece of ripped paper to another clean sheet, and to strafe it with charcoal powder. When he removed the taped-on piece, a perfect x-ray-like impression remained. The drawings offset the gritty evidence of their own dilapidation with transcendent illusionism. They are perfect, even as they are ruined.

Web exclusive, July 2014