Last summer, when I visited the house of Luis Barragán in Mexico City, I was surprised to discover in it a commercial reproduction of a Josef Albers Homage to the Square. The architect liked its idea, shape and orange colour scheme, the guide explained, but wasn’t particularly interested in the real painting. Albers’s connection with Mexico, which he described to Kandinsky as ‘the land where abstract art existed for thousands of years’, was long and inspiring: in 1935 he produced his first oil abstract painting after making his first trip there with his wife, Anni, and his first Homage to the Square while teaching in Mexico City in 1949. To me, Barragán’s decision to hang a copy of Albers’s signature abstraction looked like an act of reverence as much as of retaliation, a way of appropriating the legacy of Modernism in response to the ‘translation’ of Mesoamerican aesthetics into Western visual codes.

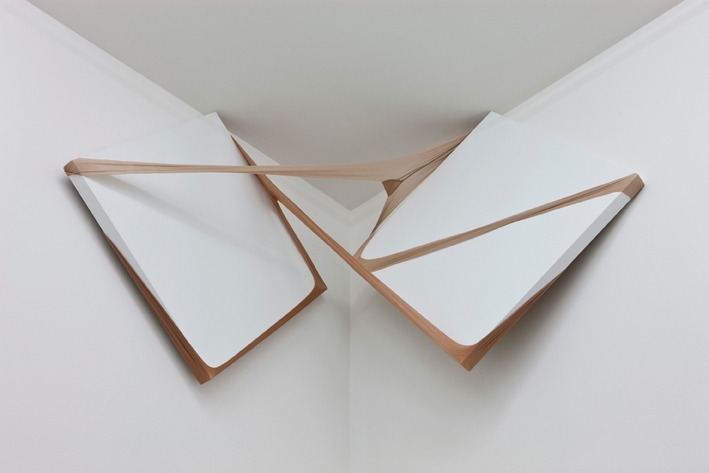

Opinione Latina 1 (Latin Opinion 1; a second stage, including more countries, such as Chile and Colombia, will follow in 2014) is united by the geographical provenance of the artists – all South American, all born between 1968 and 1980 – as much as by a similar interplay of cross- references, with Concrete and Neo-Concrete art as the consistent background. For his Homage to the Square (2011), José Dávila (born in Guadalajara, like Barragán, and trained as an architect) reproduces the three-dimensional radiance of Albers’s compositions by painting a coloured square on the wall, in Pantone acrylic, and then installing four translucent plates of glass in front of it, on a small shelf. Mexican Gabriel de la Mora also adopts the square monochrome, but his white ‘painting’ in fact comprises thousands of miniscule fragments of eggshells, glued to a wooden support (7.461, 2013). Martin Soto Climent uses stretched black and white or flesh- toned women’s tights to create variations and spatial connections between pairs of square white canvases, as if to reinstate physicality over abstraction: Light Lovers (2012) sits high in a corner, while Tights on Canvas (Double Diptych) (2012) takes centre stage on a wall.

Fontana et le Chien (2012), by Venezuelan Jorge Pedro Núñez, references Lygia Clark’s semiabstract, origamilike Bichos (Creatures), but by employing portions of vinyl records labelled ‘Fontana’, it calls to mind also Lucio Fontana, on whose oeuvre the artist has often worked. Wilfredo Prieto’s framed single jigsaw pieces (Pinochet, Apartheid, Coca-Cola, all 2012) stigmatise our inability to grasp more than fragments of larger contexts, but nod too to Cildo Meireles’s Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Coca- Cola Project (1970). Murmurs (2012) by Mexican Antonio Vega Macotela, the only large installation on show, is also based on decoding: only when kneeling on the red cushions and looking up at the pages of daily paper El Sol de México can one decipher the ads (written anamorphically, legible only from a particular angle) used by jailed narcos to communicate with the outside world.

The photos of drops of honey running on rocks by Brazilian Thiago Rocha Pitta (Untitled: from ‘Danae in the Gardens of Gorgona or Nostalgia of Pangea’, 2011) stand out oddly by simply focusing on nature. The show closes with an old video by Amalia Pica, Islands (2006), where a young man draws in the snow, step-by-step, the profile of a cartoonlike island, with a single palm tree; in the last shot, the bucket he has carried all along, is left behind, giving the illusion of a fallen coconut. A sweet, ironic farewell to all cravings for exoticism.

This review was originally published in the May 2013 issue.