A new facsimile edition of a 1959 monograph of the artist provides a timely insight into his foundational, profoundly political act of negation

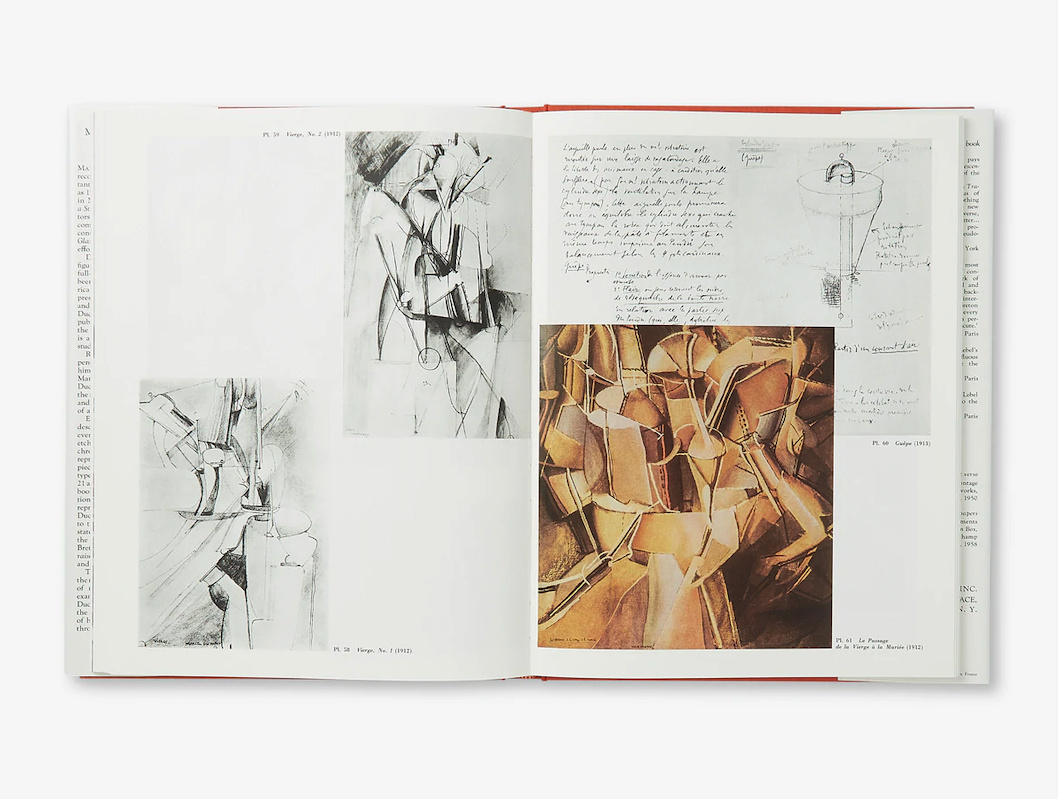

A century ago, Duchamp was just finishing a decade of work that would change the course of art. From Nude Descending a Staircase (1912), via Fountain (1917), to The Large Glass (finished in 1923), Duchamp patiently worked through questions about art’s relation to aesthetics, philosophy and its own institutions with which it would take the ‘artworld’ 50 years to come to terms. Duchamp died in 1968. The publication of Robert Lebel’s Marcel Duchamp, in 1959, in French and English translation, marked the beginning of Duchamp’s postwar canonisation.

This facsimile edition is a lavish remaking of the original in faithful detail, and collectors will covet it. (Penniless art students may want to borrow from the library, assuming there are copies enough to make it to art colleges.) But this ‘first take’ on Duchamp, long before he was an art-school-seminar mainstay, is genuinely impressive. Lebel, art historian, supporter of the Surrealists and other cultural radicals, offers a rhapsodic but fluid account of Duchamp’s life and works, with George Heard Hamilton’s translation managing to keep Lebel’s elaborate Francophone syntax readable to the uninitiated, even when Lebel is hauling the reader through the thickets of Duchamp’s more esoteric ruminations.

Unlike posthumous academic analyses of Duchamp, Lebel’s account emphasises the ethical nature of Duchamp’s strategies of evasion and negation. The supposedly arbitrary choice of the readymade Lebel interprets as Duchamp’s desire to ‘depreciate our… notion of value in order to exalt the strictly private and sovereign choice which is accountable to no one’. Individual sovereignty is not arbitrary, but unbeholden to the values of others. Duchamp refused to be professionalised by the ‘art system’, even if this meant abandoning his ‘career’. Rejecting the repetitive status of a cog in a machine underpins the machinelike, sexualised binaries of Duchamp’s cryptic works, his play with gender (his alter ego Rrose Sélavy) and his constant sabotaging of desire and visual pleasure by language and cognition. At a moment when an over-institutionalised artworld is desperate to rediscover a sense of its positive purpose and fulfilment, it’s fascinating to revisit Duchamp’s foundational, profoundly political act of negation.

Marcel Duchamp, by Robert Lebel (trans. George Heard Hamilton), is published by Hauser & Wirth Publishers