Tiravanija’s participatory works provide not just the ‘dignities of living’ but a critique of why they were absent in the first place

Rirkrit Tiravanija is a creator of purposeful playfulness and critical thinking whose work explores how use creates meaning. During the 1990s the Argentina-born Thai artist constructed an oeuvre that was best known for its extempore participatory aspect: inviting the public to eat pad thai he cooks, as seen in various iterations of untitled 1990 (pad thai); inviting it to rest, as seen in untitled 1993 (sleep / winter), for which he provided straw mats and foam mattresses in art spaces so that visitors might sleep; or even untitled 1996 (tomorrow is another day), for which he faithfully reconstructed his East Village apartment and offered the public 24-hour access to take advantage of the working fridge, cooking range and bed. These works furnished much-needed services, even if limited by resources and time, to a public experiencing the economic fallout of the 90s during which time unemployment almost doubled in New York City and Cologne, where untitled 1996 (tomorrow is another day) opened. They were, in short, a response to their immediate time and a way to track how a preponderance of meaning emerges from human engagement.

MoMA PS1’s synopsis of the 100-plus-work exhibition, titled A LOT OF PEOPLE, promises what it calls ‘“demonstrations” of key participatory works’; the exhibition announcement also refers to ‘restagings’. Without much more context, it is yet to be seen if the effectivity of extemporaneous response will continue. Tiravanija is known for his constant travel, his declarative choice to ‘never work’ and his ability to think fluidly from an interdisciplinary standpoint. From screen-printing, to cooking, to sculpting, to film – there is not a creative distance that impedes Tiravanija asking the questions he desires to ask. Change, spontaneous response and gathering people into a participatory space are necessary to activating his works. He mutually transforms art spaces and his artworks with his voracious curiosity for how audience interaction will change the situations he initiates.

Tiravanija’s gatherings are site-specific in that every new place in which they are exhibited, and every new audience that participates, changes the gathering to be unique to the setting. This is not always smooth, or even positive: in the catalogue for Tiravanija’s MoMA PS1 survey, for example, curator Ruba Katrib writes about an audience member unexpectedly responding to Tiravanija’s untitled 1992 (who comes first) by throwing eggs and ‘acting out’ in a way that ‘frightened’ artist Elizabeth Peyton, who witnessed the event.

Circulating between the values of previous art movements such as Fluxus and Dada and the relational aesthetics mode with which he was associated during the 1990s, Tiravanija’s body of gatherings invites audiences to challenge the boundary between everyday reality and institutional reality, to undermine unquestioned patterns of living and relating – such as how societies consume, often without questioning the how and why of what is available. His method of creativity is rooted to Wittgenstein’s idea that ‘meaning is use’, and across his interdisciplinary body of work Tiravanija seeks to incite audiences to consider the use of objects he recreates and displaces, to think critically about the systems that create or abate access to resources. This method stress-tests the very capacity of the museum to capture the life of the object it displays through categorisation and deracination. Tiravanija’s offerings suggest a path towards institutional obsolescence – or at least the obsolescence of the encyclopaedic museum that PS1’s parent institution, the Museum of Modern Art, represents. For the artist, such institutions should be community-mandated, -owned and -directed, and able to hold quotidian life.

Who owns what? And when? And how? And where did they get it from? Tiravanija disassembles those questions to pose yet another: how does the concept of ownership function? What are its consequences? It was while studying at the Art Institute of Chicago and witnessing its display of historic Thai art objects that Tiravanija began to question how beautifully rendered everyday items for storing oil or rice, for cooking or for worshipping lost their living essence by becoming static, unused and separated from their places of origin by violent global processes like colonisation. For Tiravanija, the loss of use is the loss of meaning. There is perhaps not a better summation of Tiravanija’s attitudes towards institutions that emerged from colonial archival practices than a quote from Israeli academic and curator Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, writing, in Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (2019), about the museum as archive: ‘The archive is first and foremost a regime that facilitates uprooting, deportation, coercion, and enslavement, as well as the looting of wealth, resources, and labor’.

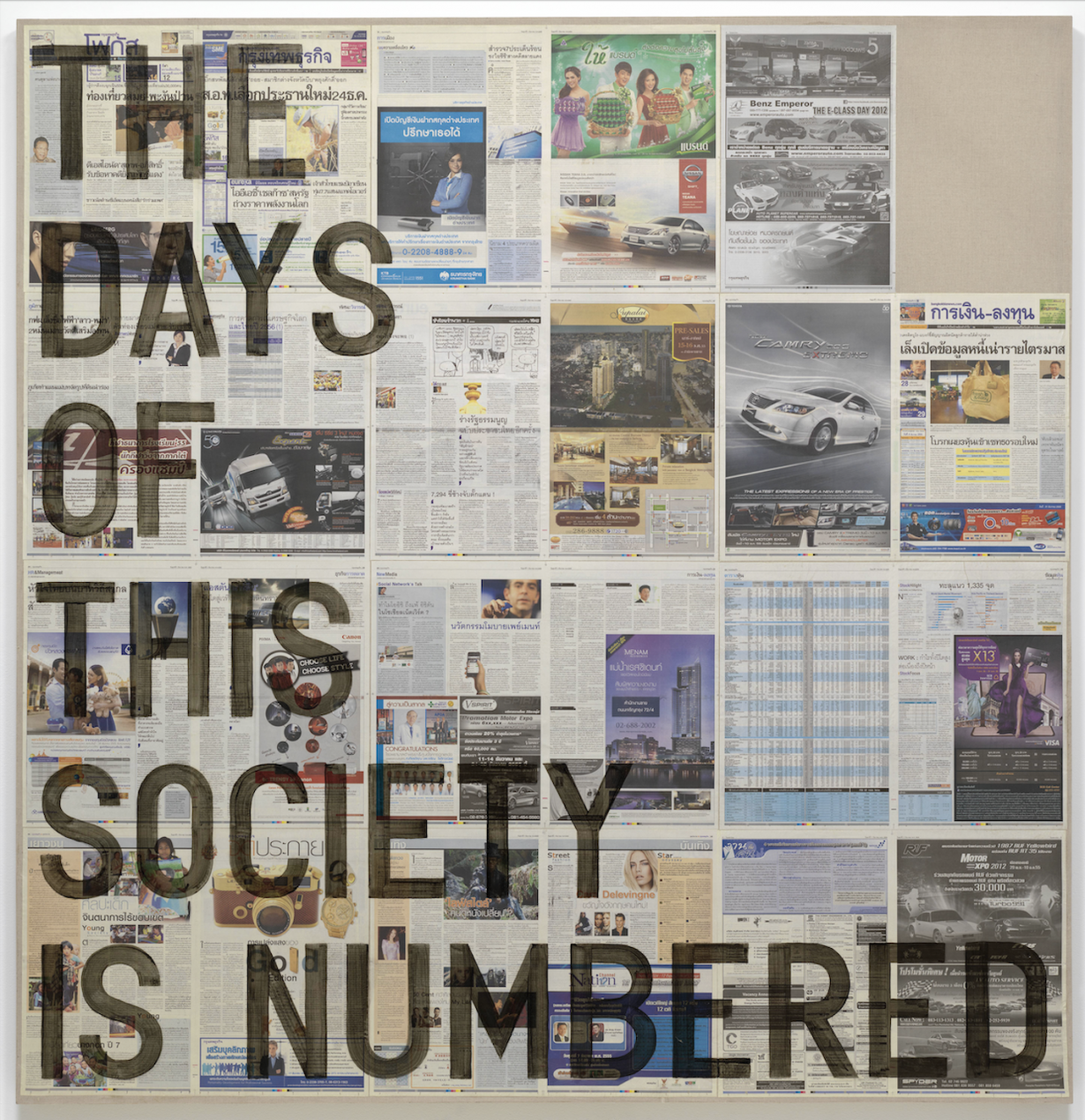

Azoulay suggests that modernity arises from the displacement of people and resources; those displacements generate vulnerabilities that are exploited on massive scales, fuelling a form of economy that requires such exploitation to survive. In 1987 the conceptual creator or provocateur or activist or artist (or whatever audiences might want to call Tiravanija) created untitled 1987 (permanently removed for display) for his thesis project. Untitled 1987 (permanently removed for display) was arranged in a small room underneath the museum’s Asian galleries, the walls lined with empty panels that in their lower-right-hand corners stated ‘works permanently removed for display at the Art Institute of Chicago’. After this thesis show (and winning an unexpected award from Gordon Matta-Clark’s estate), Tiravanija staged a related piece called untitled 1987 (text in red and black). In a dimly lit empty room he displayed on the wall a barely legible text: ‘WE DEMAND THE RETURN OF OUR CULTURAL ARTIFACTS IN THE MUSEUM OF THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO. OTHERWISE WE WILL BLOW IT UP.’ During the course of that exhibition, hundreds of Thai and Thai-American demonstrators staged a protest at the Art Institute to demand the return of a lintel to a restored temple in Thailand. The timeliness of the unexpected meeting of the protests and Tiravanija’s gestures are a testament to the artist’s understanding of the zeitgeist. Both untitled 1987 (text in red and black) and untitled 1987 (permanently removed for display) highlight the ways that larger systems normalise seemingly harmless standards for our everyday perceptions of labour and display, while suggesting Tiravanija’s later trajectory of continued institutional and societal critique. Untitled 1990 (pad thai) and untitled 1993 (sleep/winter) demonstrate how this practice is furthered by Tiravanija using institutional spaces to address social inequities when it comes to sustenance, rest and even platonic intimacy (like sharing a meal). His commentary on labour is often subtextual, implied in the subjects he undertakes, such as how the labour exploitation implicit in colonial projects is how museums gain sometimes illicit access to the items it displays. Yet over 30 years Tiravanija has also made more pithy and direct commentary, in actions such as having audiences screenprint their own souvenirs with phrases like ‘NEVER WORK’, ‘THE DAYS OF THIS SOCIETY IS NUMBERED’ and ‘RICH BASTARDS BEWARE’. The same phrases have appeared in collage works where Tiravanija superimposes them over Thai newspapers, as in untitled 2009 (the days of this society is numbered, september 21, 2009), and ping pong tables, as in untitled 2019 (tomorrow is the question); and stencils them into steel, as in untitled 2013 (rich bastards beware) (stencil).

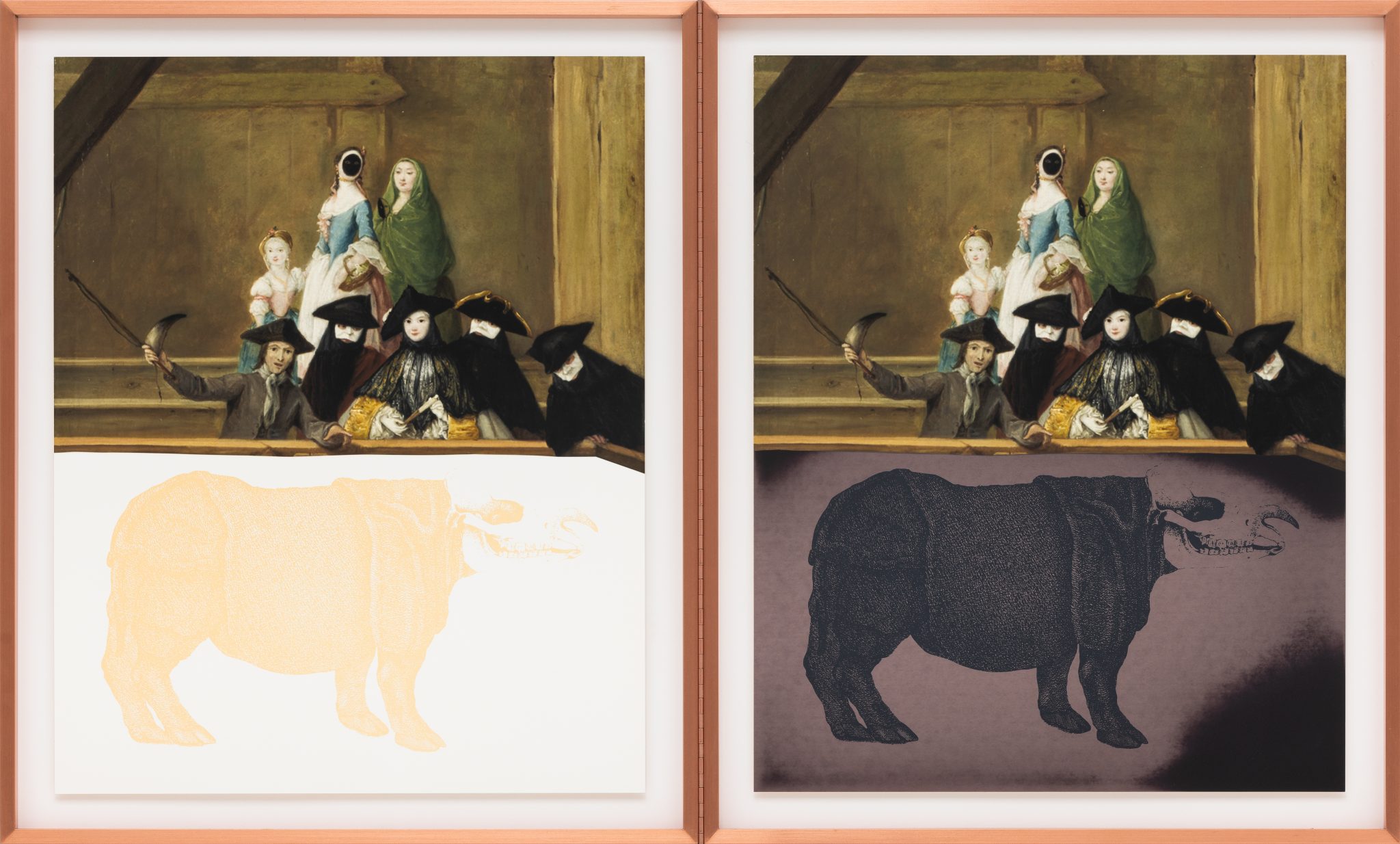

Tiravanija’s gatherings are hubs for audiences actively to engage our enmeshed dependency on nature and the vulnerability of our consciousness. More than that, Tiravanija asks if our everyday lives and systems function in the ways most critical to sustaining human interconnectedness; such questioning also encompasses a perspective on environmentalism. In artworks like untitled 1990 (endless column), the artist takes detritus from his gatherings (food waste, beer bottles, cups, etc) and stacks them in plastic bins as a sculptural commentary on excess. In an interview with STPI gallery accompanying this summer’s exhibition We Don’t Recognise What We Don’t See, he states, ‘extinction has already started’. The show centred the effects of human conquest, both of ourselves as a species and other animal life, via appearing and disappearing images of animals in juxtaposition to reprints of five Old Master paintings. In the video that accompanies the interview, there are details of art by seventeenth-century-painter Jan Brueghel the Elder in which Tiravanija erases the depictions of animals, making them only visible under UV light. The intersection of the history of the reprinted master paintings with Tiravanija’s artistic commentary, specifically in Brueghel’s The Temptation in the Garden of Eden (c. 1600), speaks to a pattern throughout history of human ideology justifying the exploitation of nature as well as colonial processes. We Don’t Recognise What We Don’t See echoes the causality between colonisation, globalisation and the erosion of stable environmental systems in untitled 2006 (palm pavilion), which Tiravanija arranged for the 2006 Bienal de São Paulo. In this installation he and his collaborators reconstructed housing designed for French colonies in Africa, in order to retrace the corporate colonisation of sites for growing palm oil and the industry’s connection to environmental and human devastation. In many ways the mundane and platitudinous ideas we commit ourselves to and how we commit (with vague statements like ‘save the animals’) are a collective decision about how we are comfortable with dying. Tiravanija’s oeuvre is among the few that actually foregrounds that collective comfort by using situational and interactive settings to test his audience’s acumen for practising the attributes most likely to make a change in how we relate to our environments.

In my encounters with Tiravanija’s work, and speaking to him, I was profoundly activated by the artist’s ability, as a maker of situations and places, to demand that we (humans) acknowledge the fear that disables empathetic interactions and gentle recognition of our interdependence with each other and nature. In a riff on the 1974 film Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, the title phrase – ‘Fear eats the soul’ – crops up throughout Tiravanija’s body of gatherings and exhibitions. Taking place in Germany, months after the Munich massacre, the film follows a love story between Ali, who is a Moroccan guestworker, and a German widower as they face social and familial judgement and alienation as a result of their relationship. Their access to one another, their human intimacy, is barred by the racism, xenophobia and misogyny in their society. The plot rigorously embodies the fear among our species of becoming the other; of living like how we perceive the other to live; or of being confused for the other in contexts where the othered individual has become symbolic of something negative. Throughout Tiravanija’s career his commentary on othering is connected to the ways he has reprised Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, even to the extent of filming a remake, titled untitled 2017 (skip the bruising of the eskimos to the exquisite words vs. if I give you a penny you can give me a pair of scissors).

When I look at certain gatherings organised by Tiravanija, they in a sense provide access to the horrifically lacking basic dignities of living: eating well, resting well, being well together and learning. Despite his cool self-representation with regard to the impacts of his gatherings, Tiravanija simmers in his focused curiosity for human habits, and our conflictual desire to be together but also exploit one another. His artworks are equally sites for inquiry, joy and practising trust. Yet Tiravanija’s demand remains the same since 1987, even if it requires an edit: give us equal access to resting well, eating well and being well together – otherwise we will blow up the museum.

A LOT OF PEOPLE is on show at MoMA PS1, New York, from 12 October to 4 March

Jessica Lanay is a writer and poet from Key West and author of the poetry collection am•phib•ian (2020)