“Every artwork has to eat itself through the self of the artist until it is something more than just the presentation of the self”

Rita Bakos was born in 1968 in Budapest, where she studied with the painter Károly Klimó, an artist whose influence on her work has become increasingly felt over the years. In the early 1990s, at age twenty-two, she moved to America for further schooling and immediately changed her surname to the more pronounceable Ackermann.

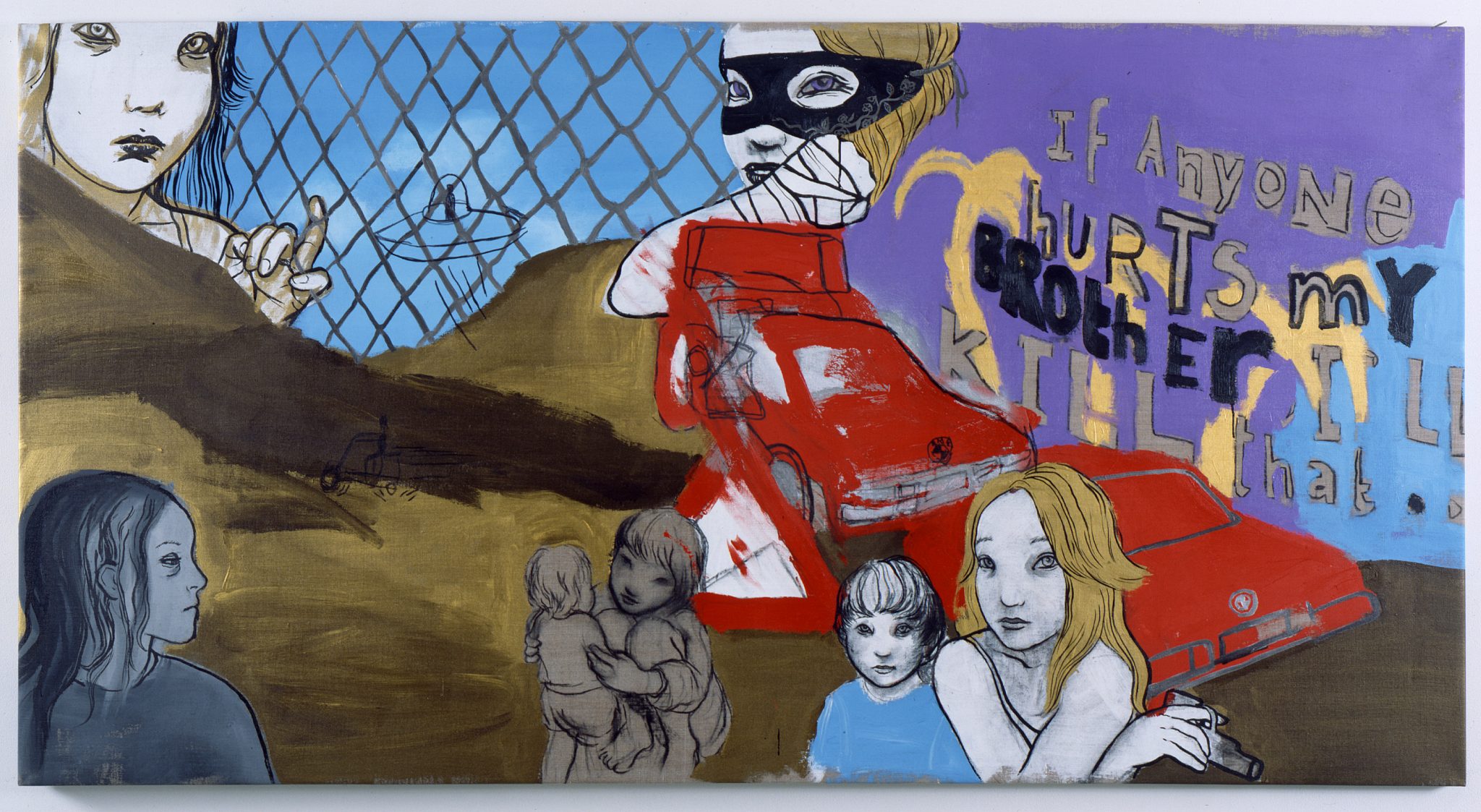

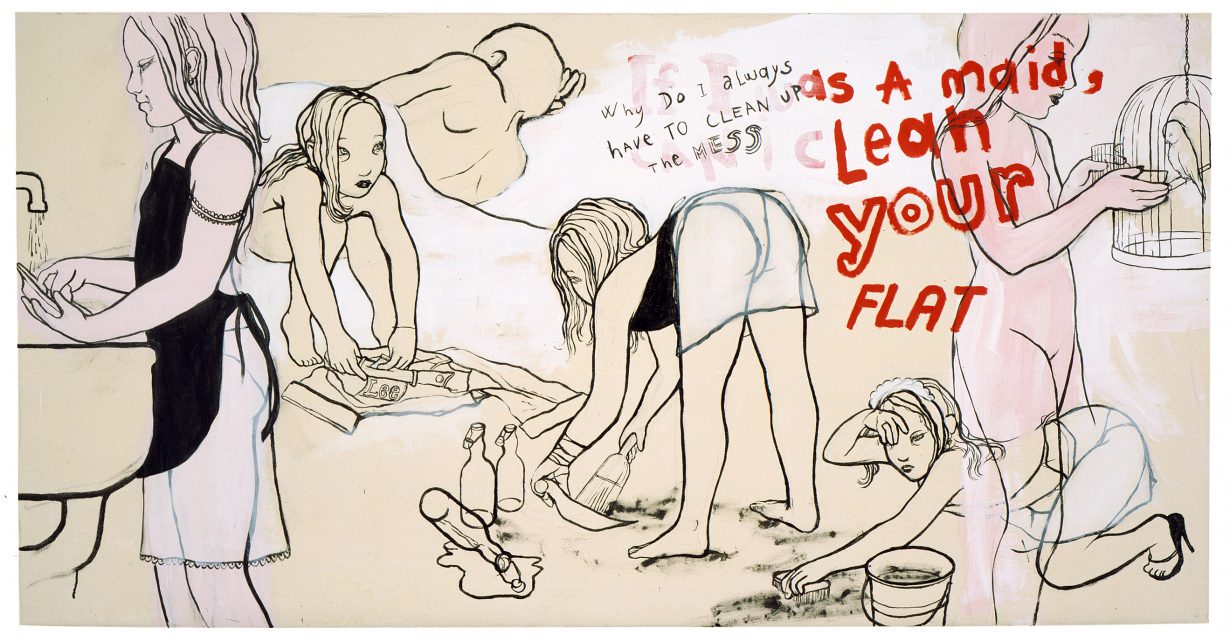

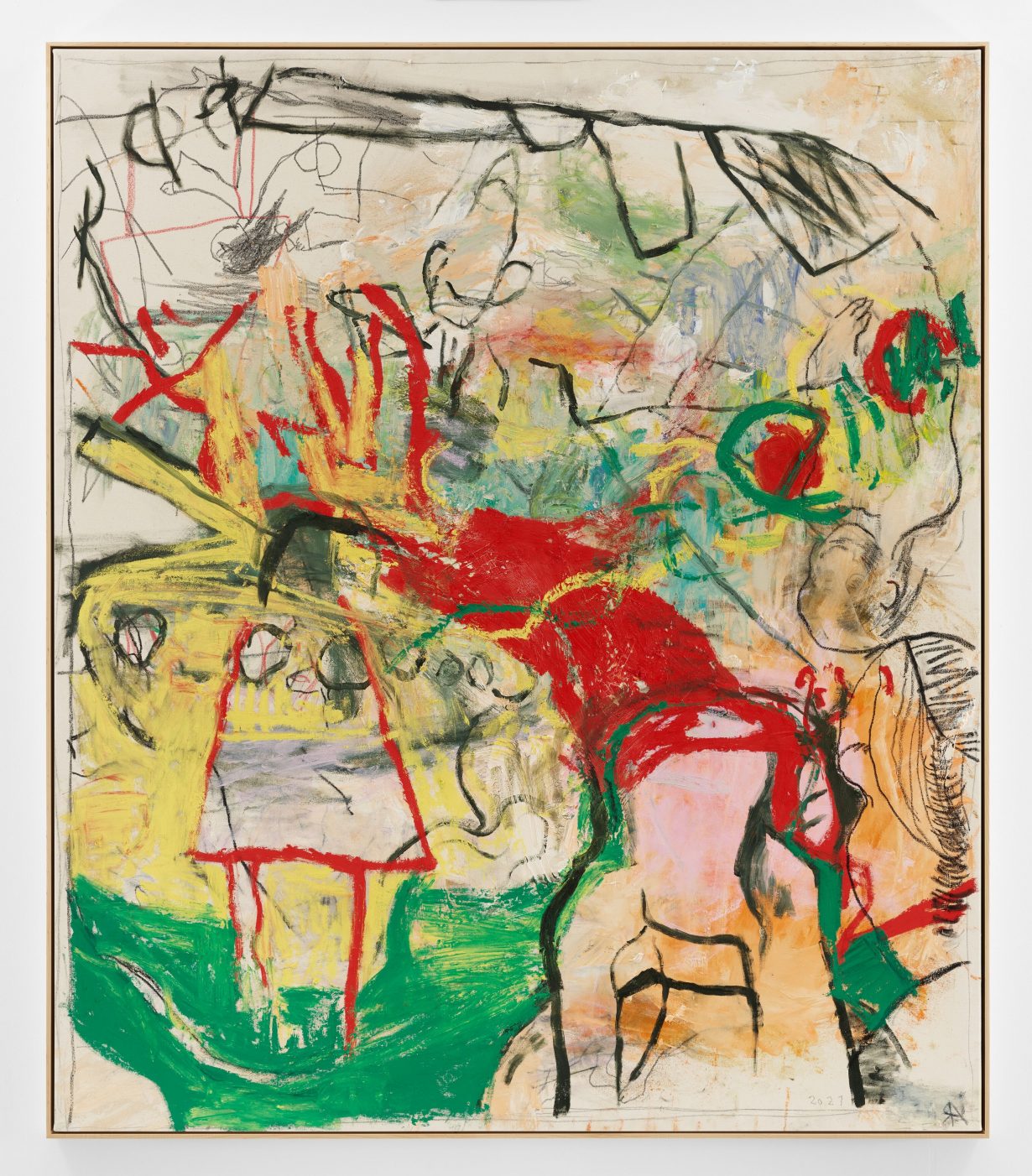

Within a few years, Ackermann wove herself into the New York art community. Her early paintings were filled with sprite-like characters whose leonine features resembled her own. Over time her work has evolved in distinct series, most of them characterised by sending her figures through radical transformations: setting them aflame, erasing them, collaging them with photographs. Most recently her paintings have taken the form of Abstract Expressionism, melting her figural draughtsmanship into colourful, corporeal smears.

As long as she has been exhibiting, Ackermann has also collaborated with fellow New Yorkers. In 2000 she cofounded the band Angelblood with members of the local experimental music community, including Lizzi Bougatsos and Brian DeGraw of Gang Gang Dance. She’s also painted with Harmony Korine, produced a theatrical show with Kim Gordon and worked with the French fashion house Chloé.

Despite Ackermann’s long-term presence in New York, she continues to speak with a rich Hungarian accent and the unexpected phrasal turns of a second language. I, however, interviewed her via email, which was at her request. For several weeks, over many exchanges, she responded to my questions with pronounced brevity. She has remarked that her work is born from the psychoanalytic emphasis of her Hungarian art schooling, but her answers did not seem to serve the purpose of verbal catharsis. Instead, many of the questions I asked her were left unanswered or were answered simply with “no comment”, as if, with every response, she was attempting to erase herself from the conversation.

I

Ross Simonini Are you attracted to ugliness?

Rita Ackermann I’m not sure what you mean by ugliness. Can you be more specific?

RS Are you attracted to things that also repulse you?

RA No, I don’t like to be repulsed, but I like funny things… Paul McCarthy’s work might be aesthetically repulsive but it’s also funny as hell. Also he’s a classical master in artistic skills so he can make repulsive things look masterfully beautiful without looking kitschy… His work also has the original innocence of a child even when it is at its nastiest behaviour. A perfect paradox, therefore. He is impossible to copy.

RS What does a “classical master” mean to you?

RA Someone who can shoot from the wrist, masterful drawings.

RS Do you aspire to this?

RA I’m not sure if it is something you can aspire to.

RS Do you consider drawing as the true indication of skill?

RA Through drawings you can see the intimacy between the artist and their works. You can see the authenticity and passion, like when the child draws.

RS Do you want your work to have the innocence of a child?

RA Probably.

RS How would you do that?

RA With radical amazement, without trying.

RS Were you an artistic child?

RA I always liked to draw and paint.

RS Did people around you consider you a good artist as a child?

RA They didn’t pay too much attention to what I was making but provided me with pencil, paint and paper that made me content.

RS Did you ever leave art behind for a period of time?

RA Not really, art was always my main passion.

RS If not ugliness, was beauty your goal?

RA Quality is more interesting… You can make a masterpiece out of trash with a sense of sophisticated lightness that shows the noble intellect of the original mind. My friend shared with me today a quote from Nietzsche that answers, for me, your question – ‘The essence of all beautiful art, all great art, is gratitude’.

RS In what way do you experience your art as gratitude?

RA That I’m able to live for and from art.

RS Do any works of art by others express gratitude for you?

RA Of course. Van Gogh’s works radiate gratitude.

II

RS Are you a private person?

RA Yes.

RS What, specifically, are you private about?

RA About everything.

RS You answer many of my questions with short responses. Are you a talkative person?

RA Sometimes… but I prefer to be quiet.

RS Your earlier representational work referenced your own image. Do you also see your newer abstract paintings as self-portraits?

RA My early figurative paintings were many things but most of all they were vessels for me to communicate because I lost my primal language but gained the ultimate freedom of expression that wasn’t available in the setting of the Hungarian art scene. Those girl figures were embarrassing, trashy and classy at once. Pop and expressionist, loaded but innocent, and most importantly they didn’t need anybody at the end, they were content with themselves. They were portraits of the invincible youth and their guardian angels. Every artwork has to eat itself through the self of the artist until it is something more than just the presentation of the self.

RS Do you ever purposely erase the presentation of yourself from your work?

RA What exactly do you mean? I’m afraid I don’t understand the question.

RS Do you ever notice something in the work that feels too much like ‘you’, something that is too revealing, and try to get rid of it, perhaps because of embarrassment or vulnerability?

RA Vulnerability is a good thing if it comes in harmony with the confidence of acceptance. There are things that can be fixed and there are things that are stronger left alone.

RS Do you think there is any relationship between your own appearance and your paintings?

RA Do you mean physical appearance?

RS Yes.

RA I’m sure there is.

RS So you don’t really see your early work as self-portraits?

RA No, I don’t see those figures as myself. I don’t think of the self much because it is in the way of making art.

RS Do you dress, in any way, like your work?

RA I dress for work and I enjoy dressing up nice when I don’t work. Artists should have a good sense of style, though – a peculiar style that is independent from fashion trends and the capsule of times.

RS How would you describe the sound of your voice?

RA I have a quiet voice.

RS Do you still make music?

RA Very rarely… behind closed doors.

RS Did you lose interest?

RA Not in music, not at all… I just enjoy listening to it more.

RS What kind of relationship do you have to music now?

RA Loving… Music is my great friend. A vessel to get lifted. It sets the altitude.

RS Attitude or altitude?

RA Altitude. Cruising altitude, like the airplane cruises above the clouds.

RS Does painting ever make you feel ‘high’?

RA Not intoxicated but elevated. Feeling elevated comes with clarity. It feels sharp and crystal clear and it hits with immense joy when a painting arrives to finish.

RS Do your paintings relate to your body?

RA I’m not aware of my body when I paint and hope it’ll stay like that for many more years. My body works like a tool to make paintings, and when you use a hammer to put a nail in the wall probably the last thing you think of while hammering is the hammer.

RS What would happen if you paid attention to the body?

RA Oh, I was unclear above. This hammer metaphor does not work at all. Simply put, when I paint I can only pay attention to the painting and which Dylan song should be playing and where is my glass of martini. The entire surface must be worked at once. Speed matters. Accidents must meet with control. Chaos has to precede order because without chaos there is nothing to clean up. Cleanup gets done while the body precisely executes the untraceable movements.

RS Do you often drink while painting?

RA Sometimes, if I’m in the mood and have the right stuff.

RS What’s the right stuff?

RA Martini could be good, I make really good and light ones.

RS How often do you finish paintings in a single session?

RA Not often, I can’t remember.

RS Would you like to finish a painting in the least possible number of gestures?

RA Interesting idea. It really doesn’t matter to me how many gestures it takes to finish a painting. What matters is that I recognise that the painting is finished.

RS What is the longest period of time you have spent working and re- working a single painting?

RA Years, I didn’t touch a painting for years… I didn’t know what to do with it and then suddenly it was right in front of me.

RS Did it look different than other paintings?

RA It really did not.

III

RS How does your current age differ from the other ages?

RA It is the best time of my life.

RS How would you describe the era we live in now?

RA Transitional times, even more than other transitional times of earlier decades. But who knows, maybe all times are transitional since the nature of our lives is transitional and we must make the best of each day that takes us closer to the time without a body.

RS Do these transitions affect your work in any way that you can describe?

RA The effects of time on anything or anybody can be only seen later, when there is far enough perspective to see the nature of changes.

RS Would you compare this era to any other historical era?

RA Each era is a completely new one, like each human has a new face that they are born with.

RS How do you feel about the way your work looks online?

RA It is not the same as it looks when you see it in person because then it’s texture. But since I look at my work on the screen while working on its different stages, I’m fine with how the paintings look online.

RS Why do you prefer doing email interviews over spoken interviews?

RA Because I can control my thoughts better in writing.

RS Would you say you are also interested in controlling thoughts in your paintings?

RA There is no total control. In a way I just keep cleaning up the painting until it looks orderly. That gives me a sense of control.

RS Do you keep your studio orderly?

RA In my way, yes, but it might look different from the outside.

RS Do you keep your house orderly?

RA Yes.

RS Are you ever obsessive about neatness?

RA Probably around the kitchen more than anywhere else.

RS Do you like to cook?

RA Yes, sometimes.

RS What are some of your most eaten foods?

RA Dandelion and potato chips.

RS Do you keep your mind orderly?

RA Yes, the mind must be kept orderly.

RS Do you have techniques for doing this?

RA Keep out the garbage. Clean the mind from bad or unnecessary thoughts. The actual cleaning itself can be a very good technique.

RS Are you embarrassed by any of your work?

RA Yes, sometimes, but please don’t ask me which ones and why.

RS Are you enjoying this interview?

RA It is like an exquisite corpse… It is almost as if it’s writing itself. I like it… Do you?

RS Very much. How would you ideally like an interview like this to affect the way someone experiences your work?

RA That the person who reads our conversation can see that the paintings are more exciting than I am.

Ross Simonini is a writer, artist, musician and dialogist. He is the host of ArtReview’s podcast Subject, Object, Verb