As Give Me Paradox or Give Me Death at Museum Ludwig, Cologne demonstrates, Horn’s art has always had an inexorable quality

One advantage of a practice that emphasises the instability of everything – from individual identity to the world’s weather – is that even your retrospectives, in momentarily unmooring familiar works through recombining them, can function as conceptual acts. In Roni Horn’s Give Me Paradox or Give Me Death, which features some 100 works by the American artist, dating from the 1970s to the present, flux begins with the title, which replaces the word ‘liberty’ in American-independence advocate Patrick Henry’s famous 1775 statement with ‘paradox’. The phrase now feints, wobbles; a bit poetic, a hard-to-grasp mission statement. If there’s an overarching paradox in Horn’s work, though, it’s that while her art is almost always technically still, it seems somehow in quivering motion.

The show begins on firm(ish) ground with the well-known This is Me, This is You (1997–2000): two grids, 48 photographs each, of Horn’s big-eyed niece Georgia Loy Horn. The groupings sit on facing walls so that you must pivot to compare them, and it takes time to register – or try, imperfectly, to hold in memory – the minute differences in these apparently identical groupings of a girl growing three years older; photos here that resemble each other aren’t twins but cousins, taken seconds apart, change layered on change. A few rooms later, in a.k.a. (2008–09), 15 paired photographs of Horn herself from different periods of her life – often, almost spookily if in a stage-managed way, wearing the same expression decades apart – you might think you’re seeing Georgia again, such is the family resemblance. There’s no permanence in solid objects, either. Nearby is Soft Rubber Wedge (1977), a slim 3m-long floor-based minimalist sculpture whose title describes it, delicate enough to pick up imprints of the various floors it has sat on over the decades. When next shown, it’ll change and accommodate again. In context, this entity, shaped by its environment, feels almost humanised.

Perhaps in keeping with change’s heedless inexorability, some things you’d expect from a Horn survey don’t show up, like her lovely paired metal sculptures (cylinders, globes, cones) whose geometry is faintly off, generally placed apart, foxing comparison; but maybe This is Me already covered that base somewhat. Instead the exhibition leans, perhaps too heavily, on works on paper. These range from small 1980s pigment-and-graphite images of plangent, slightly dissimilar coupled blobby forms – which oddly posit Robert Rauschenberg as a possible influence – to her epic, virtuosic linear abstractions, begun during the early 1990s, scissored up and neatly puzzled back together to incorporate myriad visual stutters, and accompanied by tiny, scribbly addenda recording places and names, suggesting former homes, former relationships, undone by time and halfway recomposed in the mind. A year-long series of diaristic collages from March 2019–20 finds Horn at her most improvisatory, slapping together found texts from literature and newspapers, old film stills, weather reports (‘heat wave broke’, for 2 July 2019) – the latter a reminder, perhaps, that one big existential subject ghosting Horn’s interest in the unfixed is climate change. (‘I’m not sure what I could do that wouldn’t be about the climate,’ she’s quoted as saying in the exhibition guide.) The sequence ends as the immobilising pandemic starts; on the last entry, she’s written, paradoxically, ‘I am paralyzed with hope’.

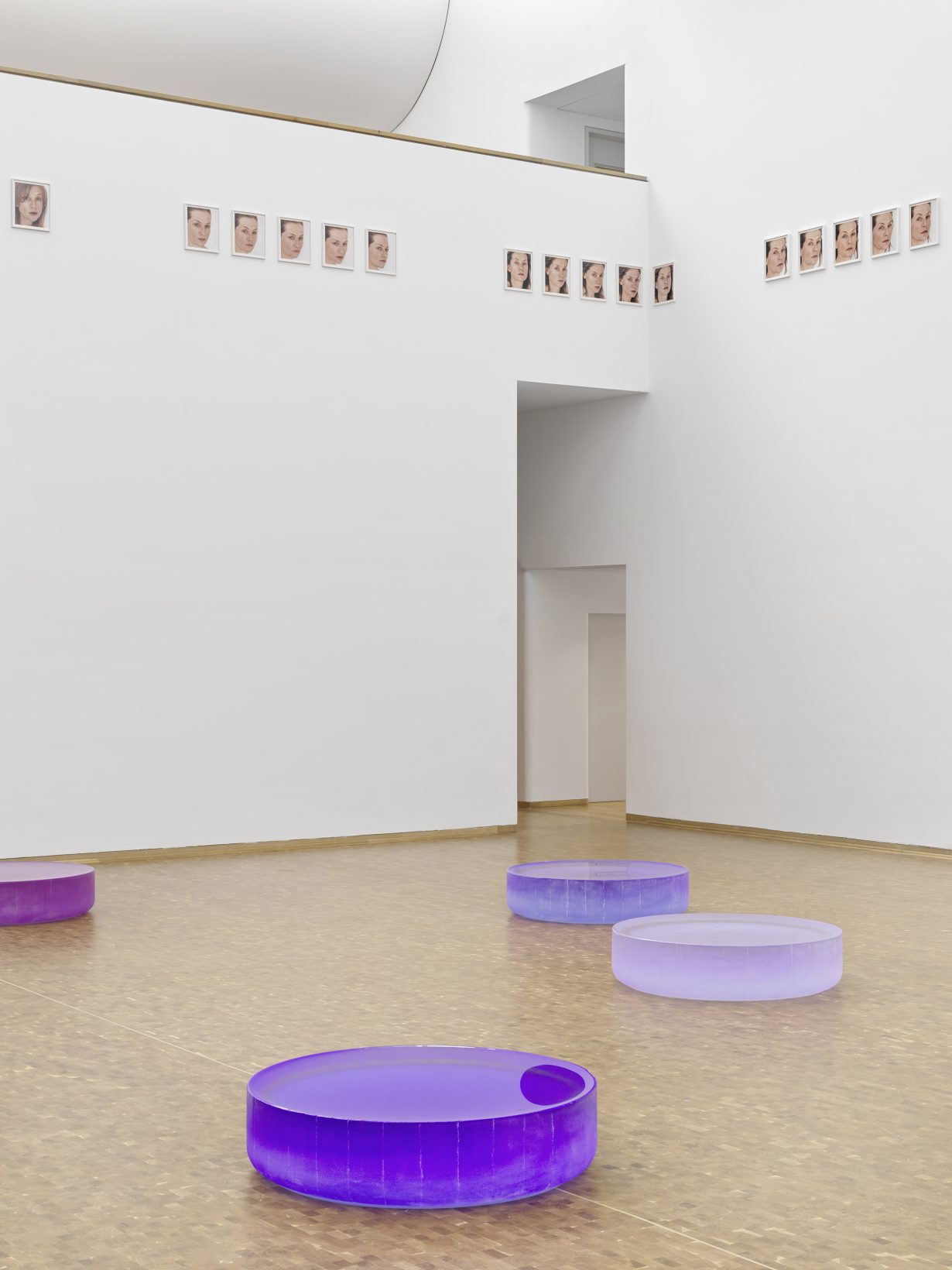

While the show’s layout is a bit squirrely and labyrinthine, veering unexpectedly into annexes, it seems to end – and peak – with a time-spanning pairing. In a big, high-ceilinged room, Horn has dotted the floor with recent examples of her characteristic glass sculptures, like giant hockey pucks in shades of blue, icy white, mauve, purple. They stand still while light and reflections bounce off their tops, whose high polish suggest these objects are shallow jars filled with water. Among the reflections are a series of quintets of photographs, placed high on the walls: the modular series Portrait of an Image (with Isabelle Huppert) (2005–06). Here, the French actress beloved for her emotional scope acts out (or displays) all kinds of moods, each grouping offering five variations; a skilled actress doing this complicating, of course, notions of selfhood even as she renders the fact of containing multitudes. While anchored in Horn’s emphatic thematics, the specific combination of sculpture and imagery is insistently beautiful and makes an abstract kind of sense, but it’s hard to say why. Right and wrong at once, it gives you, or at least me, paradox. And even if Horn repeats it, you’re reminded, it’ll be somewhere else, another time, another audience, and won’t be the same.

Give Me Paradox or Give Me Death at Museum Ludwig, Cologne, through 11 August