In parts Victor Frankenstein lab, wunderkammer, and naturalist’s study, GOLEM 2022 gestures towards collaboration and the agency of organic matter

Piece by piece, Ruangsak Anuwatwimon’s monster is taking shape. Only a few parts of his anatomically precise model of the human musculoskeletal system are in position: frontal and maxilla bones, teeth, one eyeball, a few vertebrae. But a glance around Gallery VER reveals more are coming. Stowed in metal trays on a shelf are a trachea, eyelids, ears and pieces of the cervical spine, while finger bones are arranged like fresh archaeological finds on a table alongside an exploded skull model and an atlas of human anatomy. Come exhibition close, a complete incarnation of the golem – the earth-based creature of Jewish mythology – will be threaded from the ceiling, to float like some deranged, sinewy puppet.

Anuwatwimon’s multidisciplinary practice – which melds arcane lore, natural history, anthropology, environmental science and conservation biology to create material-based meditations on ecosystems upended by human extractivism – has already led to memorable outcomes. These include: dioramas of river plains made from fish bones and recreations of critically endangered species such as the Bhutan Glory butterfly, Sindora wallichii tree and Schomburgk’s deer. At other junctures, he has burnt once-living things – from a Belgian horse to Cavendish bananas – and used the ash to create delicate sculptures that resemble parts of the human body, such as the heart and mandible.

Foregrounding the stages of a laborious process, GOLEM 2022 is both of a piece and a marked progression. Part Victor Frankenstein lab, part wunderkammer, Anuwatwimon’s evolving display at Gallery VER is the industrial assembly line of a two-part exhibition project. Over the duration, samples from the rare flora and fauna specimen collection arranged along one wall are being taken offsite and burned, and the ash then compacted and carved, using the CNC machine behind a dust curtain in the corner, to create reproductions of specific parts of the human anatomy. Guest performers are systematically assembling the pieces at four public sessions.

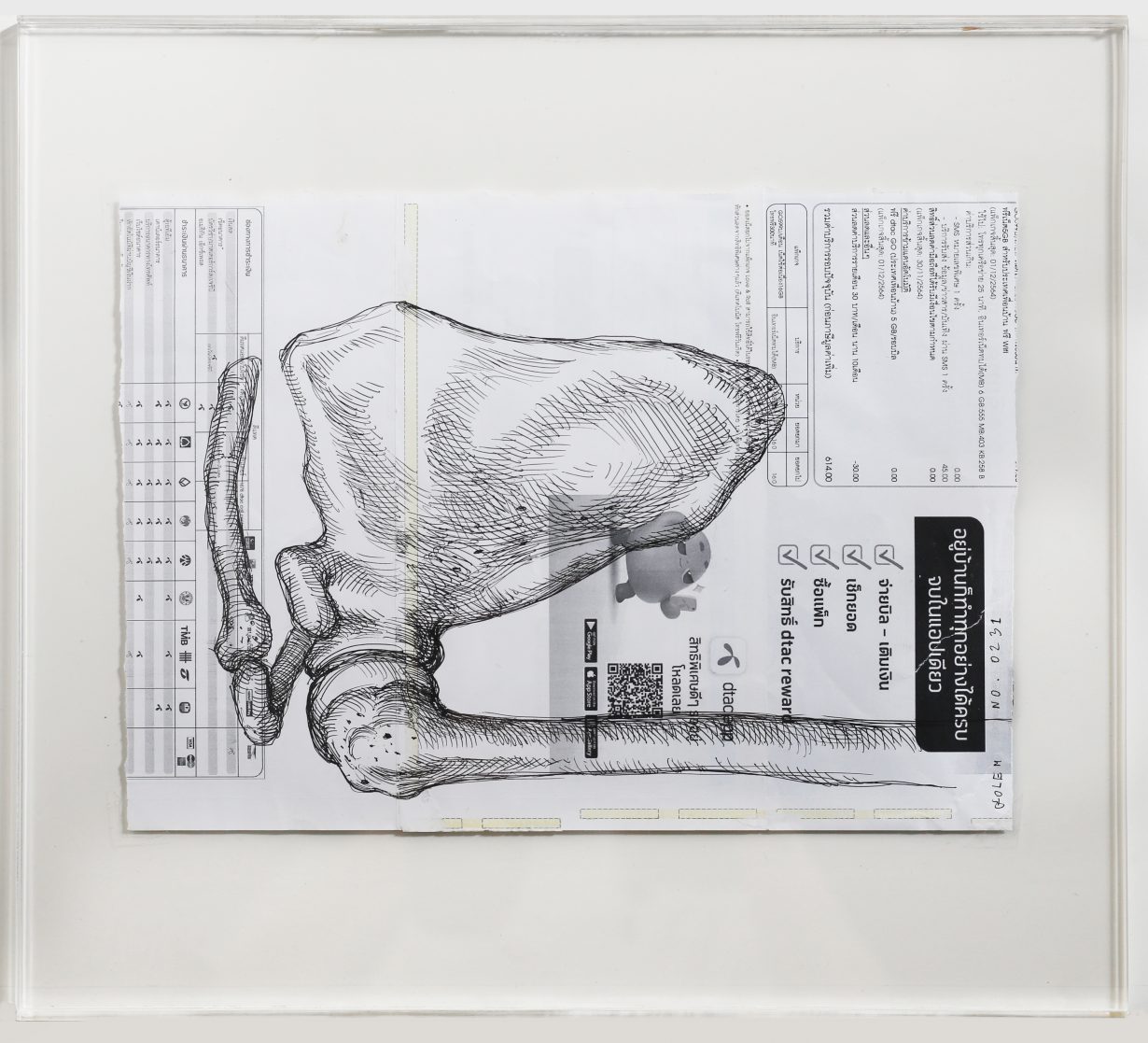

Meanwhile, the companion display at SAC Gallery feels like a rarefied space for thinking rather than toiling. Instead of Anuwatwimon the mad scientist-alchemist, here we find Anuwatwimon the tenacious taxonomist and bookish naturalist. Hundreds of his precise pen drawings of bone and musculature are filed away in numbered folders. A low shelf flanked by bamboo floor mats is lined with reference books, such as Michael Keevak’s Becoming Yellow: A Short History of Racial Thinking (2011). And in a black-walled second room is a dramatic installation: three 1:1 drawings – of a mongoloid woman, of the human bone system in an exploded view and of the blood vessel network – unspool onto the floor from hanging paper reels.

In these sketches and reference points, we find many of the preoccupations layered richly, like geological stratum, through Anuwatwimon’s artmaking: science through the ages, environmental ethics, Gothic horror, race concepts and classifications, contemporary art’s obsession with the uncanny. But above all, the display is a repository of his long-term research into the many folkloric lives of the golem – both a clay-made humanoid brought to life through Kabbalistic magic, and a mutable metaphor used to connote fear, control, power or redemption over many centuries.

Since first appearing in the Talmud, golems have been conjured for countless reasons. Some of these amorphous artificial men did no more than obediently fetch water or chop wood, but many others defended Jewish communities from anti-Semitic attacks and pogroms. Unfailingly, a Rabbi learned in Kabbalah would create them by investing an inanimate lump of clay with ‘an unreasoning, automatic life when he placed a magical formula behind its teeth,’ as Gustav Meyrink wrote in his 1915 novel The Golem. But exact techniques were diverse, ranging from reciting combinations of the Hebrew alphabet to circumambulating dust piles.

At Gallery VER, Anuwatwimon is invoking this mythical tradition: making flesh his own anxieties and fears, issuing his own instructions. Key to his alchemy is the conceptual linking of each base ash to the anatomy it reproduces. Various thinkers, including anthropologists and traditional Chinese medicine specialists, have been enlisted to help him twin specimens with body parts. Quotes sourced from online references, printed on A4 sheets fastened above each corresponding bone, elucidate the winning arguments: why his golem’s left ear is made from abalone shell (its use in Native American jewellery), for example, or the trachea from the bulb of the Himalayan fritillary lily (its use in cough syrups and Chinese medicine).

The symbolism of all this isn’t, at first glance, subtle: how many living things must we annihilate to build just one of us? When does our obligation to be the best version of ourselves end and our obligation towards that which we exploit for our own utility and perfection begin? Is this the version of ourselves we want to be?

However, there are resonances beyond Anthropocene folly and demise. Made from the ash of found specimens collected over 20 years (no living thing was harmed), Anuwatwimon’s ghastly and cockeyed creature is arguably as evocative of the action-led models of the sustainability movement – such as upcycling and circular economies – as it is symptomatic of our ongoing extinction event. Free of tedious eco-fatalism, his fabrication workshop gestures towards collaborative processes for constructively solving the problems at hand and reasserts the agency of organic matter – all while satirising our raging hubris. In some old Judaic tales, the compliant golem gets drunk on power, threatens the creator it approximates and so must be deactivated through a reversal of the spell. But in Anuwatwimon’s ecocentrist telling, the only monster who needs bringing down a peg is us.

GOLEM 2022 – Uncanny at Gallery VER, Bangkok, through 19 June