The artist depicts queer men of colour in genre scenes that are at once nostalgic and speculative

Painting in a style that falls between illustration and academicism, Salman Toor depicts queer men of colour in genre scenes that are at once nostalgic and speculative. The long-limbed and paunchy characters in Toor’s world are seen gathered at parties, picnics and parades thick with bodies and sketches of bodies, enacting bygone or imagined encounters with friends and lovers. Wish Maker, Toor’s first major New York exhibition since his institutional debut at the Whitney in 2020, weighs 19 of his paintings at Luhring Augustine’s Chelsea location against 44 of his works on paper in the gallery’s Tribeca space. Here, Toor not only portrays viable alternatives to a heteronormative world, in the form of queer spaces and sociality, but also accentuates his draughtsmanlike pentimenti to represent, within his own fabulations, other images that might have surfaced – and to which it seems he could still return.

Wish Maker speaks to itself across the borough and across mediums. Some pieces in Tribeca, like the charcoal, ink and gouache image Three Kissers (2024), correspond to works in Chelsea – in this case, a slightly larger oil painting with the same name. In both, two men lean expectantly towards a third, their hands busily caressing his face and back. Oh Father (2024) is another image that recurs: a composition reminiscent of Baroque painter Juan Rodríguez Juárez’s Spaniard and Indian Produce a Mestizo (c. 1715), Oh Father depicts a gay couple with a baby confronting an older man who has his hand on the head of a subdued woman. Despite the rift between the groups, the couple stands embracing one another and their child.

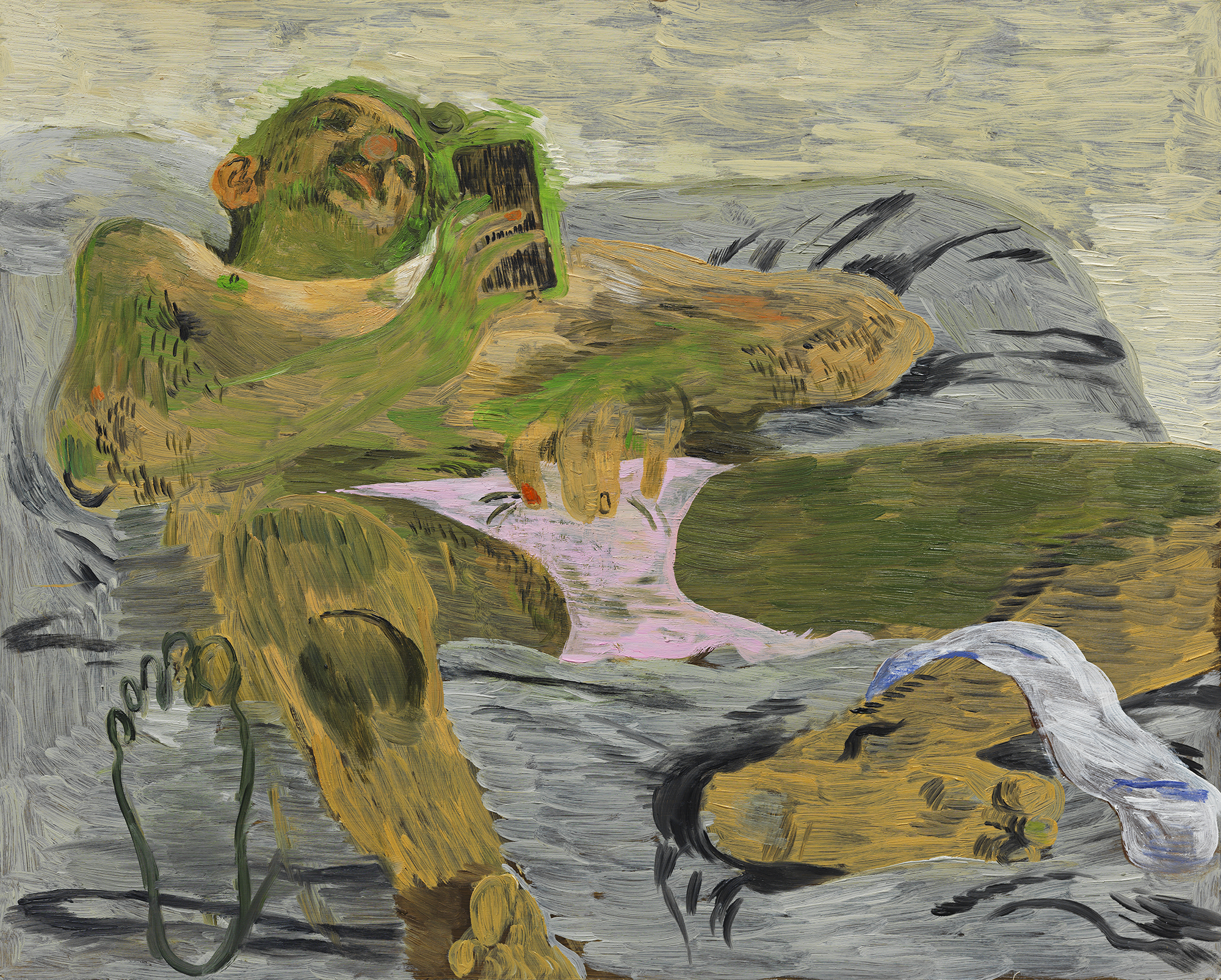

Oh Father, the oil painting, is suffused with an emerald-green hue that has been Toor’s signature since 2019. (Nearly all his works in Chelsea feature monochrome palettes – most are green, but some are yellow, coral or violet.) Strategically placed highlights crown some figures with halos, and accent colours like the Philip Guston pink on the underwear of the reclining man in The Scroller (2024) draw attention to quotidian details. When interviewed in BOMB, Toor compared his green tint to ‘night vision’, alluding to a kind of sight that is surveillant and technologically mediated. With this in mind, his predominantly greyscale works on paper, which forgo expressive pigments and emphasise line over volume, resemble X-rays. Whereas colour filters cloak Toor’s figures in their romantic world, the grey tones reveal that world to the viewer.

While Toor’s images are, on one hand, palimpsests of art-historical precedents – The Scroller, for instance, harks back to Courbet’s Origin of the World (1866), and Beach (2023), a work on paper in which a hairy male figure with wind-tossed locks poses on a foamy shore, recalls Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (c. 1485) – on a literal level, too, Toor’s works feature layers of half-erasures and revisions. Next to the figure’s left hip in Beach is a severed hand, grey and mortified, which seems to have been abandoned when the figure’s arm was raised. A bodily trace is also left in the charcoal, pencil and ink version of The Scroller (2024): a sketch of a foot haunts the composition’s bottom-left corner. Toor reprises this ghost foot in the painting as a kind of artificial pentimento. Rather than being sketched out and later rejected, the trace here is a deliberate addition that counters the subject’s voluminous flesh, a reminder of an unrealised idea preserved for future consideration, the way queerness as an ideal may be, in the words of José Esteban Muñoz, ‘distilled from the past and used to imagine a future’.

Wish Maker at Luhring Augustine Chelsea & Tribeca, New York, through 21 June

From the Summer 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.