The artist’s works in Mad in Pursuit at Modern Art, Paris challenge our expectations of industry standards

Since her first solo exhibition, in 1992, the British artist Sarah Rapson has acquired a well-deserved reputation for being ‘difficult’: difficult to write about, difficult to engage with. She is both a supreme conceptual strategist and a windup merchant par excellence – an artist who makes you suspect you’re an idiot and goads you into proving otherwise. Mad in Pursuit’s title comes from French author Violette Leduc’s novelised 1970 autobiography, and in this context could be read several ways: does it refer to us, desperately pursuing a means to read the work on show; or to Rapson herself, chasing – what? – our engagement? Regardless, the show is demonstrative in its inscrutability, which is not the oxymoron it might seem.

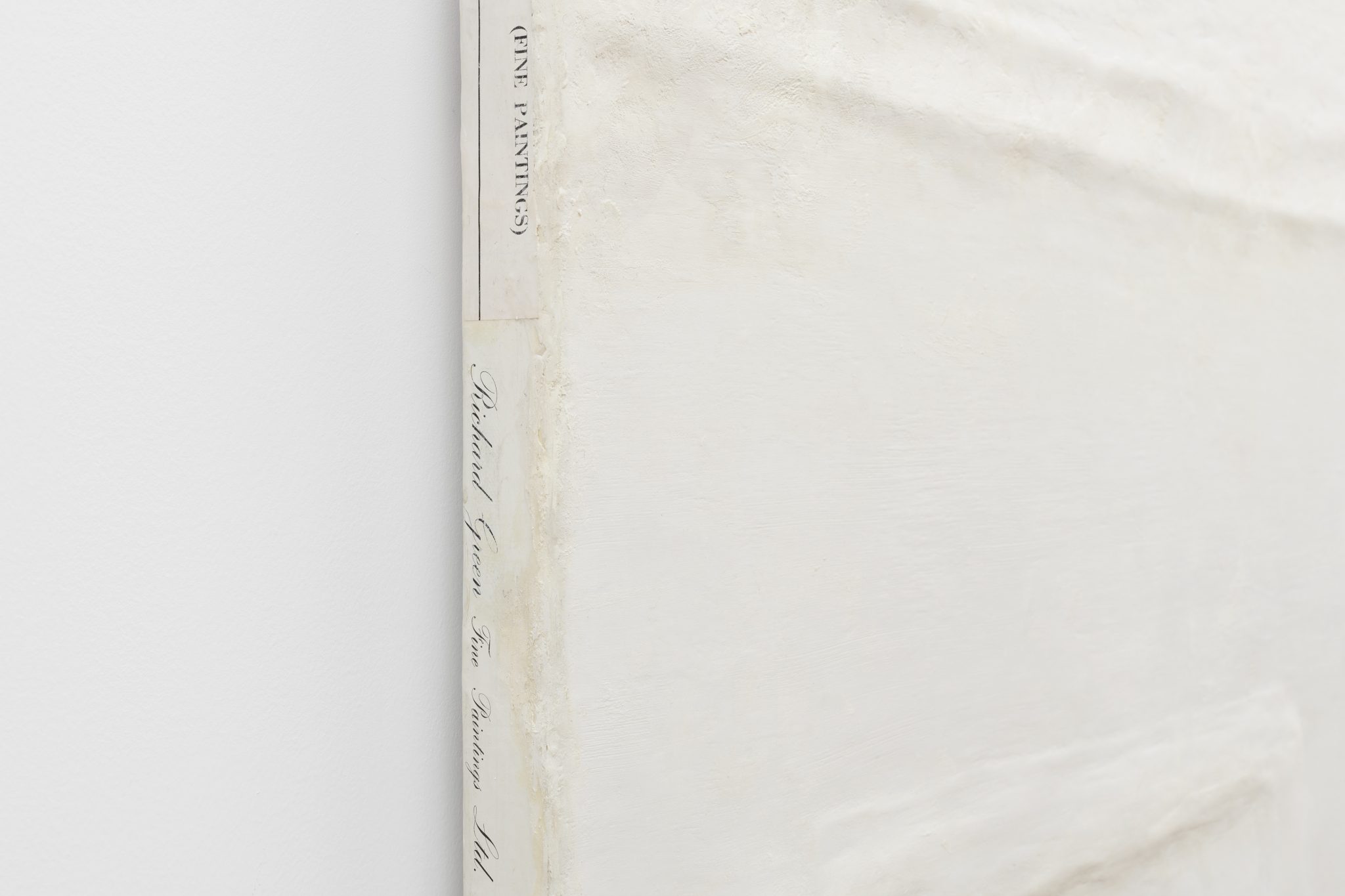

The exhibition assembles around a dozen recent paintings, some large, some small, some formed of multiple canvases. Most are cut to irregular dimensions and contain – pace the list of works – ‘printed matter’. Some of this matter is visible. Titles allude to artists (Camille Claudel, for one, lends her initials to CC I. and CC II., both 2024 ), or the production and sale of their work. Fragments of paper or card printed with the logos of blue-chip art dealerships line the sides of several canvases, and the artist has published the text buried deep below the paintwork of Consortium (2023) as a printout; it bears choice sentences from art market articles. Nuance-signalling scraps torn from art publications – one from an old copy of Apollo showing an installation shot of a Monet exhibition, another a picture of a writing desk ripped from a furniture catalogue – might appear to impart great significance, but thicken the plot still further. That’s as explicit as it gets. Rapson has concealed all other ‘matter’ under layers of bone-hued oil paint or occasionally black pigment, the former sometimes applied thinly enough to expose the outlines of the materials buried beneath. The works are quite beautiful in a minimal-punky sort of way, and might in some cases – with extreme myopia – be mistaken for the paintings of Rapson’s touchstone, Agnes Martin.

One series, comprising Newhouse I., Newhouse II. and Newhouse III. (2024/2003), was first exhibited 21 years ago, then subsequently reworked (we know not how) in the artist’s studio in Bridport, Dorset. Each work presents you with an apparent contradiction in terms: the paint masks rectangles of printed materials, about the size of double page A4 spreads, their outlines left prominent; they appear to conceal, to show the unshown. This dynamic demands an unusual degree of active engagement: text or images hide themselves as if wanting to be found, while what is exposed – those gallery logos, for example – seems broadly in tune with the art industry concerns evoked in the titles. If at first this seems forbidding, you might start to perceive a ludic, even procedural dimension to the show. Clues – in the form of the aforementioned, readable fragments of text – are scattered throughout, eventually building up to hints.

Those references to the grand art publications and galleries (the ‘consortium’ referred to earlier?), and to artistic heroes – Martin, Claudel – suggest some degree of disenchantment with the way that even the best art is displayed, chronicled and sold. By way of response, Rapson’s work does its best to suppress those conventions. The very absence of a press release goes some way to tearing up the unspoken contract between visitor and gallery: why should a (skim-) reading of a work of art be handed over in a convenient package? Rapson puts a challenge to our expectations of such industry standards – and, in the process, dares us to have a bit of fun with it.

Mad in Pursuit at Modern Art, Paris, 15 March – 20 April