A group exhibition across two venues in New York explores news coverage of the ‘War on Terror’, and its psychological impact on a whole generation

During the early 2000s, news networks began covering wars and conflicts at an unprecedented scale, with many airing graphic images from combat zones around the clock. SCREEN MEMORIES explores the psychological impact this media environment had on those growing up in the Middle East during that decade. Across two venues, works by Huda Takriti, Yara Asmar and Mona Benyamin – who came of age at the turn of the twenty-first century in Syria, Lebanon and Palestine, respectively – reinterpret the artists’ early encounters with televised geopolitical crises. Reconstituting the intricate point of view of the child spectator, several works address the complex interplay between experience and witness, while others tackle the quandary of what it means to author a personal narrative that also involves the lives of others.

At Abrons Arts Center, Takriti’s silent two-channel video Starry Nights / Or, of that night when stars disappeared (2025) recreates the impressions of a perceptive and rightfully disoriented child. Displayed on adjacent monitors, the work investigates the artist’s memory of the live broadcast of the 2003 ‘shock and awe’ operation in Baghdad. Most of the video consists of lines of text in Arabic and English flashing on black screens. The language feels intentionally naive: ‘The sky became an unlimited canvas of black…’, writes Takriti, ‘green terror / orange terror / red terror / yellow terror / white terror… And my father says at half past six in the morning, I am there’. The video ends with a montage of scenes embodying what must be ‘green terror’ – soldiers carrying out a ground operation, their actions recorded on a nightvision camera – without any accompanying descriptive text. Takriti’s memory, this suggests, is fragmented: visuals have been severed from language, sounds erased or lost.

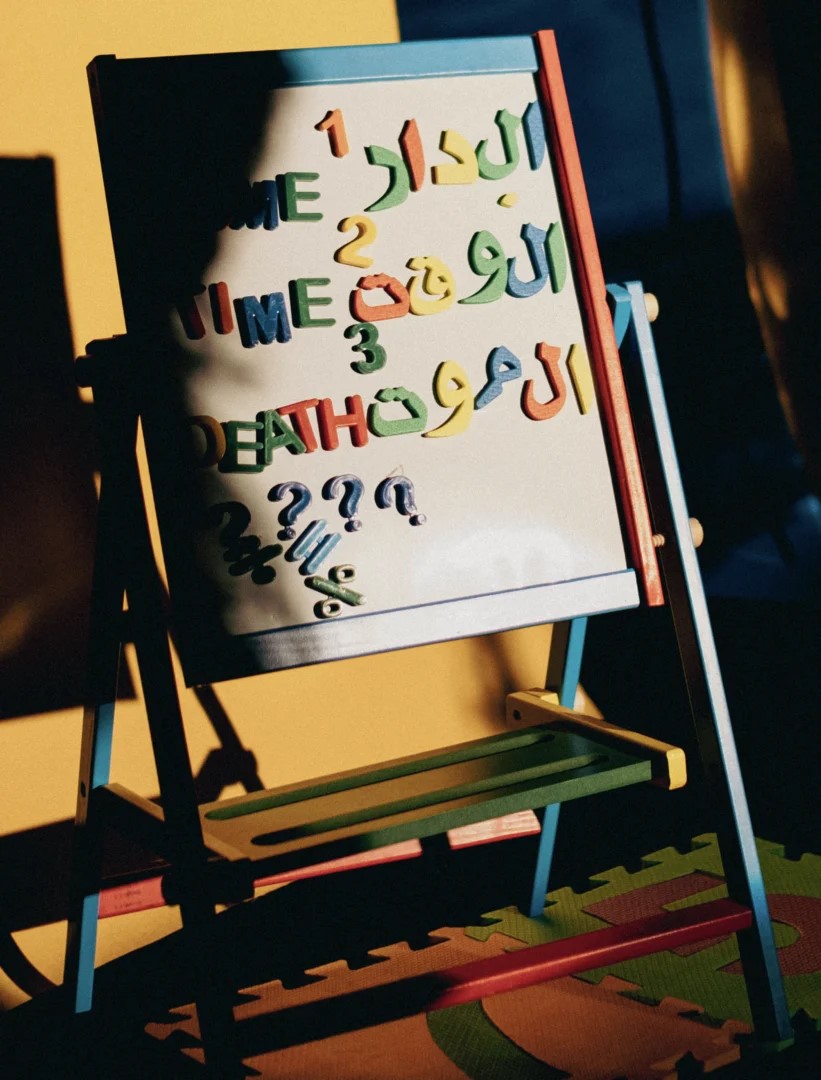

‘Screens’ here allude to the technology used to disseminate news and visual culture, as well as, according to the exhibition text, the false images that a young mind – as per Sigmund Freud – uses to mask memories of traumatic experiences. Nearby, four monitors display Asmar’s video series Mr. Samuel’s Teatime Stories for Good Kids & Confused Adults (2024). The videos take place in a surreal, quasi-domestic setting where numbered foam tiles – pieces from a child’s playmat – scatter and spiral on the floor and ceiling. The episodes are hosted by a woman wearing a large costume head shaped like a clock and an elderly man in evening dress, who banter, sing and answer letters. Each episode ends on a disquieting lullaby, with refrains like “Home is nowhere” and “A funeral’s a party”. Something is amiss: “The sunlight is different here”, the hosts sing. “The sky is a little too clear.” But the source of the strangeness goes unstated.

Likewise, in Benyamin’s works, overtly theatrical performances mask what is implied to be real distress. In Tomorrow, again (2023), a single-channel video framed as a news broadcast from Palestine, anchors played by Benyamin’s parents deliver purposely exaggerated displays of emotion in lieu of reportage. The artist’s mother weeps as security footage flashes onscreen, showing a man activating a smoke bomb on a coach bus. The artist’s father laughs while standing before recorded scenes of largescale destruction and dispossession. Benyamin’s dark humour is reiterated in her single-channel video Trouble in Paradise (2018) and her film installation Moonscape (2020). In the former, her parents play a comedic duo, delivering deadpan jokes, mostly in English, about marriage, death and the Israeli occupation. In the latter, presented at partner venue Cuchifritos, they dance and sing in a dimly-lit lounge bar, while Benyamin, separately, initiates a Kafkaesque email chain to replace her restrictive Israeli passport with one that would allow her to move freely (between the earth and the moon).

The least resolved and most interesting aspect of screen memories is this complicated intergenerational collaboration. Towards the end of Moonscape, we see Benyamin’s mother singing at a mic, her lips moving out of sync with the song we hear. ‘Separation was destined upon us’, the translated subtitles read. ‘My Israeli passport stands between us my dears.’ She seems to be ventriloquising Benyamin’s own anxieties and frustrations; she speaks for her child and, simultaneously, her child speaks for her. The didactics inform us that Benyamin’s parents also ‘do not speak English and were fed their lines [in Trouble in Paradise] through transliterated cue cards’, and that they survived the Nakba in 1948 and the Naksa in 1967 but ‘never shared their memories from these major events’. Considering this, Benyamin’s parents seem to participate in what art historian Claire Bishop terms ‘delegated performance’ – enacting their real identities as displaced Palestinians as part of the work of art. It is their theatricality that provides them a measure of opacity, even as they become characters in the next generation’s story.

SCREEN MEMORIES at Abrons Arts Center and Cuchifritos Gallery + Project Space, New York, through 14 April

From the April 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.