Thirty-four works are listed as being in Michael Dean’s exhibition, but given that several are combined to make new works, the actual number could be more – or fewer, depending on how you see it. All bar a few are assimilated into a presentational structure: waist-high MDF partitions containing MDF chairs and tables, which divide up both galleries. The titles are unwieldy, ranging from HaHa to HaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHa HaHaHaHaHaHaHaHaHa. I think I’ll refer to the works as ‘the locks’ and ‘the tongues’, for that is what they represent for the most part.

They evoke torture, salt licks, laughter, charcuterie

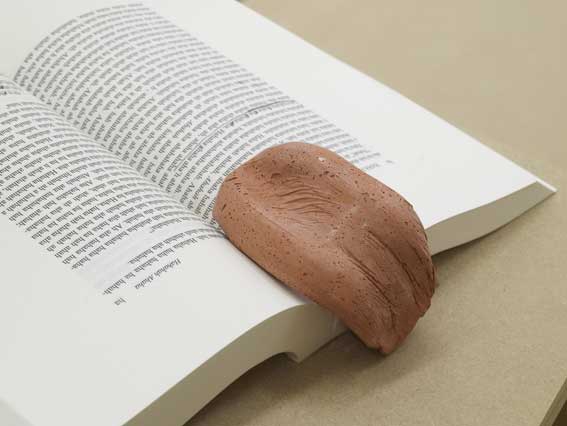

Both series of sculptures (all 2013) are made from concrete and glue. The locks are scaled-up approximations of actual mechanisms, crude travesties of precision-made objects, ‘the driver pins and spacer pins, knitted like fingers’, to quote Mike Sperlinger’s exhibition text. The tongues are comparatively realistic. When not physically incorporated with the locks, they droop from the edges of tables, mark the pages of books or sit there like saintly relics. They evoke torture, salt licks, laughter, charcuterie. The locks are equally suggestive, full of latent movement, like physical stills from dark animations: one can imagine the tumblers disintegrating as Jan Švankmajer turns the key. All have a shapeshifting character, especially Ha Ha Ha Ha Ha Ha Ha, an even hybrid of tongue and lock, geometric on one side, floppy on the other.

The coolly machined furniture that accommodates these objects is as basic as possible, operating as a Platonic backdrop that throws the objects’ materiality into greater relief than might be achieved by presenting them in isolation. But it also countermands their autonomy, making them appear like forms, earthly derivations of archetypes. It’s this contradiction that holds your attention, and there are counterpoints to prevent it becoming glib: a concrete cabbage, cast directly from a real one, is rolled casually into the mix, and small piles of coins function as precarious supports for some of the locks and tables.

This was enough for me. But Dean has added some typescripts, cryptographic ‘translations’ (as I understand it) of appropriated texts using an alphabet consisting of just Hs and As. While these reams of laughter apparently hold the key to the sculptures’ evolution (and perhaps their titles), their physical inclusion feels unnecessary, a didactic nod to the installation’s linguistic origin. If the words have to be here, would it not be better to integrate them with the work’s sensate effects, rather than juxtaposing them as a bibliographic addendum?

This review originally appeared in the September 2013 issue