The Indian artist uses charcoal in ‘Quieter Than Silence’ to conjure statuesque processions of armoured women in a defiant refusal of the violence enacted against them

It’s easy to forget what charcoal marks on paper can do. But you get a reminder when looking at those deployed to build up powerful bodies in Quieter Than Silence (Compilation of Short Stories). According to an exhibition text, Shakuntala Kulkarni rediscovered, among other materials, handmade khadi paper, made from fibered cotton rag, and charcoal pencils in her Mumbai studio while confined at home during the 2020 and 2021 COVID-19 lockdowns. She began using them to draw ageing women, tracing the bulging, sagging and sunken contours of bodies transitioning from one life stage to another. The artist was born in 1950, so one can assume that her study was self-reflexive. Take the lines tracking moving limbs on naked bodies in Imbalance (2019–20), a series of waxen drawings on museum acrylic sheets and glass, which reflect her attempts at forming yoga poses that no longer come so easily.

But the initial introspection of Kulkarni’s charcoal studies seems to have transmuted into a playful curiosity. She began clothing her figures in garments inspired by the deconstructed, monochromatic designs of Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto, among others, with hairstyles and headdresses calling on a world of references, from Frida Kahlo to the matted hair crowning the head of a woman Kulkarni often saw on the street. Swaha (2020–22) is an index to these influences and interpretations. Twenty black-framed dermatograph pencil and acrylic paint drawings on glass show women standing in profile, plus another viewed from the back, each wearing a black dress and holding a headdress above her head. What looks like a Duchampian bottle rack is among those crowns.

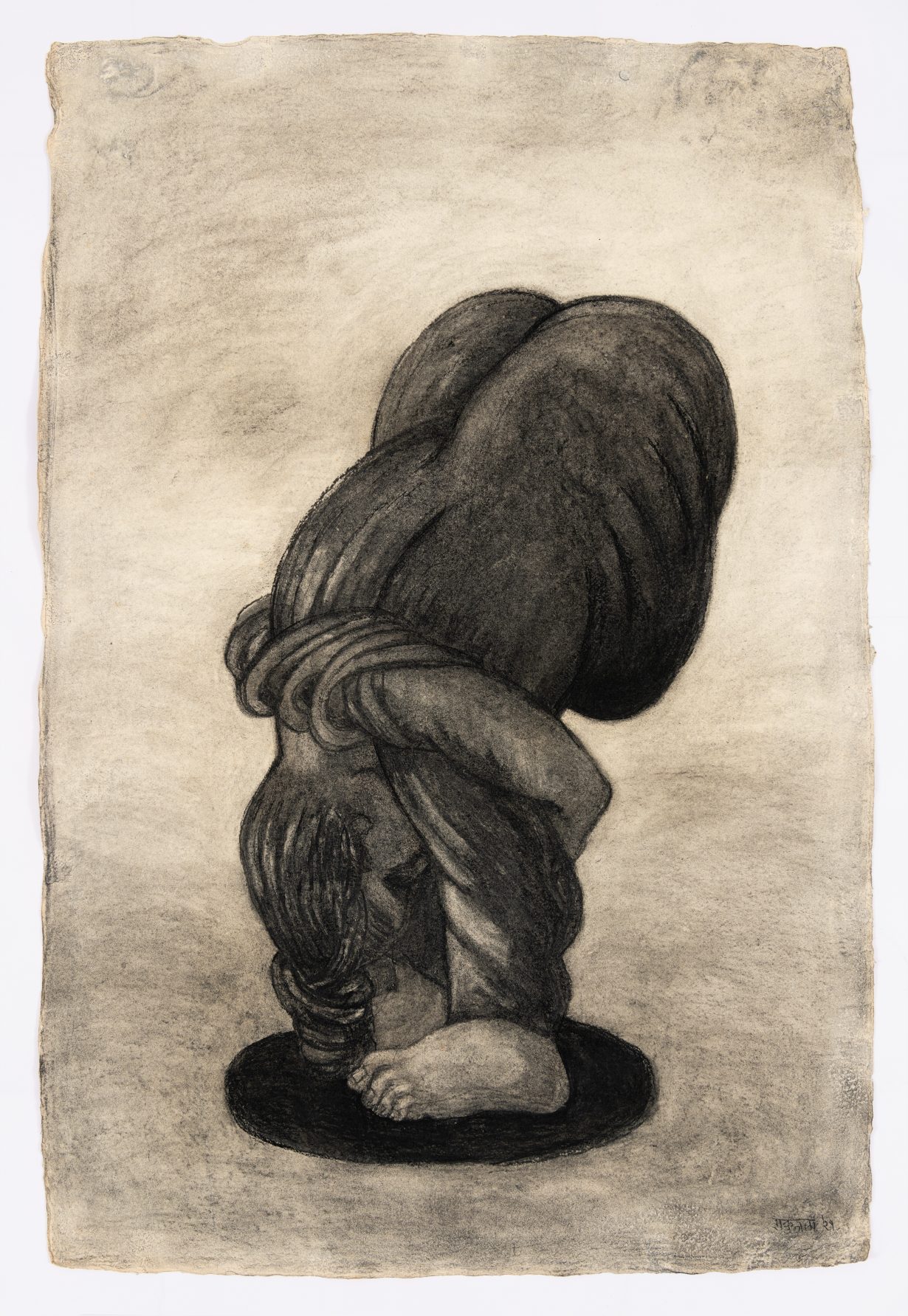

Hanging in a line to form a friezelike procession, Swaha acts as a precursor to Stuck in the shadow (2021). Fourteen drawings on khadi paper, each depicting a clothed figure, are the captivating result of Kulkarni’s lockdown charcoal explorations, when a fixation with a figure skater’s decisive, twisting movements began to imbue to every captured pose. Frozen in a moment of exuberance and tension, the bodies are lined up across three walls, like deities populating ancient metopes. In one a figure performs a standing forward-bend, their head pressed to their knees and arms wrapped tightly around their legs. In another, a figure with a gravity-defying ponytail forms a three-point-landing stance. Weighty charcoal marks on sinewy paper create volume and, at times, ethereal luminosity. In one drawing a woman in a half split, whose winglike cape rises up behind her, gazes outwards. Her forehead, nose and lower lip pick up the light before clarity recedes to dense shading.

Statuesque figures with heavy breasts, swollen abdomens and exaggerated buttocks are among the group gathered here. Wearing black structured garments and Medusa-like head-dresses that often cover their eyes, they stand on compact black circles. This tension between containment and action calls back to Kulkarni’s 2012 exhibition Of Bodies, Armour and Cages, also at Chemould Prescott Road. Synthesising references from Gothic punk to Tudor and classical Indian dance costumes, Kulkarni used cane to create sculptural body armours and helmets, which she has worn for various performances, as forms of self-protection and self-isolation. Versions of them are worn by figures falling to the ground in Fallen Warrior (2019–21), a set of small drawings arranged on a long table, expressing what Kulkarni has described as the helplessness and resignation that she felt within and around her amid the pandemic.

That sense of helplessness fuses with rage, anguish and sorrow in Lullaby (2019–20), eight compositions of grieving mothers cradling the bodies of their dead children in the style of the Pietà, their black robes framing each limp body. Triggered by news stories of young women being raped and killed in India, Lullaby laments the unspeakable injustices to which Kulkarni’s work has long been attuned. Lying on tables, these protest drawings are watched over by the heavy charcoal forms comprising Stuck in the shadow. Standing like sentries, they invoke the silence of the show’s title while resisting their own designation, and its implication of imprisonment by the darkness that shapes them. Appearing almost three-dimensional, each figure seems ready to emerge from their fibrous foundations, poised to petrify, with the sheer weight of their presence, anyone who means them harm.

Shakuntala Kulkarni, Quieter Than Silence (Compilation of Short Stories) at Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai, 9 March – 6 May