The iconic independent arts space is leaving its premises after 30 years

The video trailer for The Substation’s annual month-long arts festival Septfest (4–28 March), usually taking place in September to mark the centre’s anniversary, strikes a tragic note. Amid footage of a flickering lightbulb in the building, as well as historic footage of past happenings hosted at the venue, the current co-artistic director Raka Maitra says via voiceover: “At the end of July The Substation will be no more. And what was plainly obvious will disappear. So it’s only appropriate that our farewell gift to Singapore is about the margins and the marginalised… The Substation has been here for 30 years, the only refuge for the fringe. I’m scared that we can also be forgotten.”

Singapore’s oldest independent art space will have to vacate its premises of 30 years this July. The 45 Armenian Street building will undergo a two-year renovation, after which it will become a multi-tenant arts centre. When the refurbishment is complete, The Substation may return to the space, but it has to share the building with other groups. In a lengthy letter to Today newspaper, Tay Tong, a director at the National Arts Council (NAC), which funds The Substation and is also its landlord, explained that such a model is necessary ‘with the increasingly vibrant arts scene, and artists and arts groups seeking physical spaces to support their work’. He added that the impending renovation work wasn’t news to The Substation’s administration, which had also been ‘regularly engaged’ on these developments.

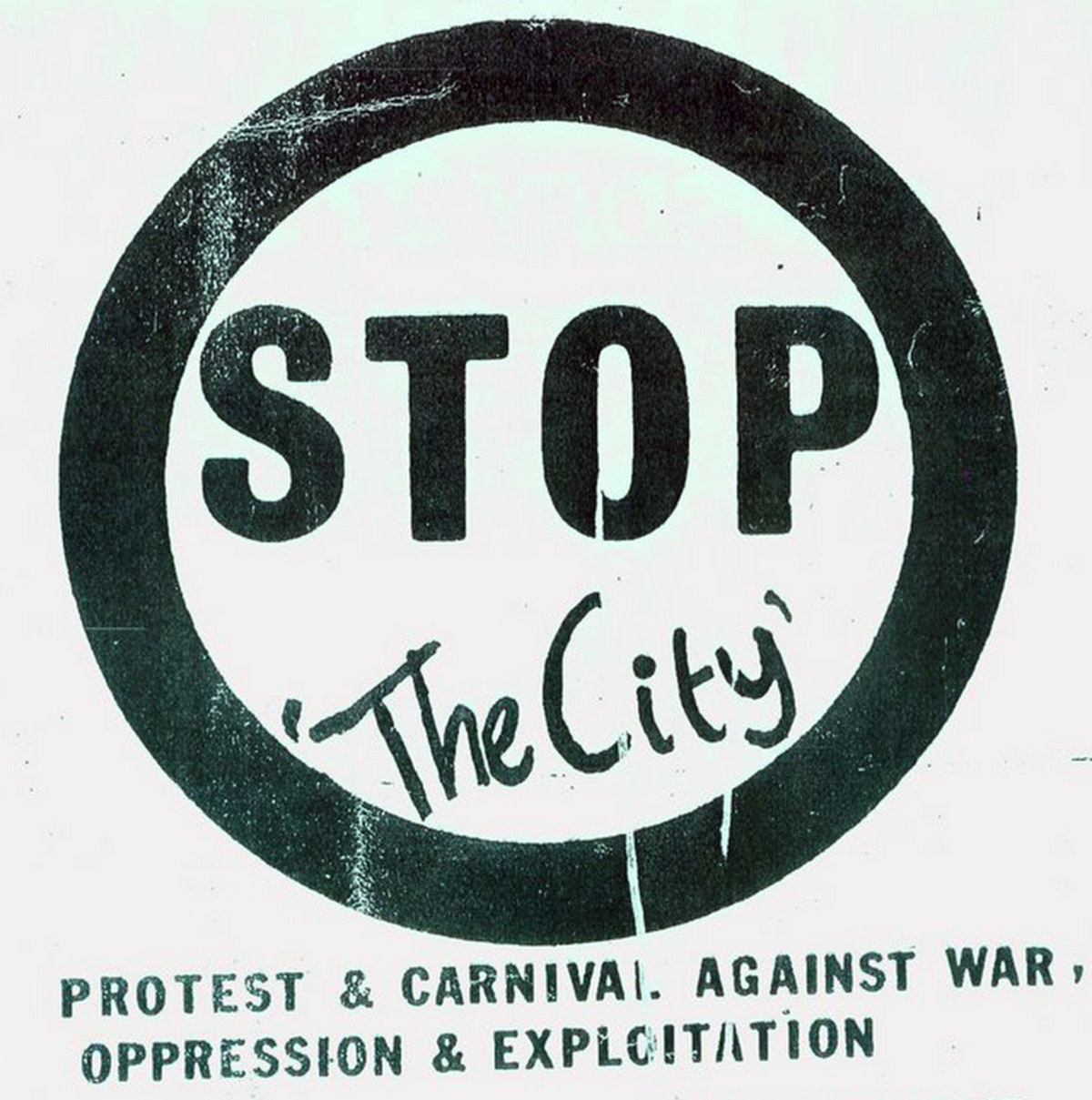

His meaning is clear: NAC is not taking The Sub by surprise. This crisis has been brewing for years. But still, news of The Substation’s cutback was met with consternation by parts of the local arts community. Many arguments rest on the historical and symbolic value of the institution. For many, it represents a hard-won space for freedom of expression and experimentation, established by a key figure in local art history, playwright-director Kuo Pao Kun. A mentor figure to many artists, he was known for his multilingual plays that spoke to Singapore’s history and identity, as well as his championing of the arts. He lobbied the government to have The Substation set up in 1990. Housed in a former power station in the city’s historic civic district, the centre has a multidisciplinary ethos, with a black box, art gallery, studios and working spaces. Over the years, it became known for showcasing young visual artists, experimental performance and independent music.

For a certain generation of artists, The Substation’s status is tied to Kuo’s legacy, which is sacred. In a Facebook post Thirunalan Sasitharan, theatre educator and artistic director of The Substation from 1996 to 2000, asked, ‘Why can’t Substation get back all of its space after the upgrading?’ He appealed to its pedigree and track record. ‘Has it not already proven its worth many times over, are there so many other urgent competing needs for arts spaces that [the] master plan calls for the erasure of a venerable place for the arts founded by arguably the greatest artist Singapore has produced to date?’

For others, the question is whether The Substation should continue to function as an organisation without its original building (after all, the centre is named after its venue). Artist-curator Alan Oei, who was The Substation’s artistic director from 2015 to 2019, doesn’t see the point of such indignity. He wrote on Facebook: ‘My own take is that if we have to leave the building, then The Substation should shut down permanently. It will be a scar and shame that we have to collectively bear. And if it should come to pass that we forget it, then [its] absence speaks to who we are.’

Is it such a bad thing for The Substation to move out of its building? Its founder certainly did not peg the concept to the venue. In farewell comments given to The Substation in 1995, quoted in the 25th anniversary publication of The Substation, Kuo said, ‘I don’t feel there’s a need to say goodbye on leaving this job. Because The Substation is first and foremost NOT a physical space. It is more a spiritual space, a cultural consciousness, an impulse turned into an urge, then into an ideal, then into a reality. It has become part of our existence – greater sense of freedom to express, and accept new, different, challenging things.’

Not that we should be bound to the founder’s vision of the arts centre, but even to his most loyal and literal followers, Kuo’s words must suggest a degree of flexibility. Times have changed; maybe it is time The Substation does, too. Moving out of its current location may also provide an opportunity to its leadership to critically rethink its structure, identity and place in a changed landscape. For years, The Substation has positioned itself as an alternative space that resists commercialism and instrumentalisation by a state-directed agenda of a ‘creative economy’. During the 1990s, perhaps it was that radical place. As Singapore’s first independent space dedicated to the arts, it grew in tandem with the contemporary art scene and the careers of the pioneering generation of artists that included Tang Da Wu, Lee Wen and Zai Kuning. In the 2000s, while the arts infrastructure got more crowded, The Substation was pitted against newer and swankier arts centres such as the Esplanade performing art centre, The Arts House and the revamped National Museum of Singapore. Somehow it clung on, still under the banner of supporting slower, experimental and process-based work across different artforms.

But is The Substation, as Maitra claims, the “only refuge for the fringe in Singapore”? I’m not so sure. Speaking for the visual arts alone, smaller, nimbler outfits have sprung up, such as Grey Projects and soft/WALL/studs, both dedicated to research and exhibition-making, and independent outfits such as Supernormal and Coda Culture. These organisations receive government support, but on a project basis, giving them more flexibility overall. Granted, they are all visual arts-focused, unlike The Sub’s multidisciplinary model, but their size and focus allow for easier shapeshifting. Supernormal, for example, has already moved spaces twice, and is currently without a physical space. Yet it recently did a pop-up exhibition at the Gillman Barracks for Singapore Art Week. The spirit of these spaces is also different. They are less bound by all-or-nothing binaries such as centre/margin, oppressive state/free artists, open/shut. Perhaps they reflect the ethos of a new generation of practitioners who favour more open and collaborative models of thinking and artmaking – which may ultimately be more productive ones today.

During The Substation’s Space, Spaces and Spacing conference last year, academic Cherian George made a good point about The Substation. He argued that Singapore, like many other countries, has been facing a democratic recession since the 1990s. Back then, Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong was “signalling a new kind of political culture” that allowed for more openness. George added, “I would go so far as to say that if The Substation did not already exist, and if a Kuo Pao Kun tried to propose one today, the current government would reject the idea. The Substation came into being during a small window of opportunity from the late 80s to the mid-90s, which has since closed.”

Photo: AIRISU / The Substation

The Substation was a product of its time, springing up to fill a gap when the art scene was less developed infrastructurally and the political climate was more forgiving. Its structure seemed right then: a monolithic, standalone, catch-all space for all things independent, non-commercial and experimental. But things have moved on. Its scale now seems clunky. It seems weighed down by its own symbolism. The actual building is creaky. And around it, the scene has diversified and granulated. Its funding body, NAC, has become more of a sophisticated bureaucracy, whose largesse comes with greater strings attached. Given Singapore’s rapid urban development and The Substation’s role in local art history, it would be a shame if it were to close down permanently. It may survive yet, but not in its current state. What it needs is a cataclysmic reinvention.

Update, 2 March 2021: The Substation’s board of directors announced the permanent closure of the centre. The full statement can be found here.