As a supplementary to Documenta 8 in Kassel (and some would say infinitely more enjoyable) Kasper König devised a sculpture project in Münster. It was something in the nature of a treasure hunt, and, as long as you were prepared to enter into the spirit of the thing, were physically fit and able, with a bravery bordering on foolhardiness and could read a map in an interpretive rather than literal manner, you were away.

Assuming that you arrive in Münster by train you go straight to the Information Bureau where you acquire Map Mark 1, which has a few haphazard circles indicating possible sites of sculptures but no identification. You are adjured to go direct to the Landesmuseum, where you will acquire Map Mark 2, a catalogue and a bicycle. We reached the Museum by a circuitous route which took in, amongst other sculptures, a Scott Burton park bench which looked like any other park bench and a pair of gigantic cherries on a granite column by Thomas Schütte which we learned afterwards was both sexy and an ironic comment on the city of Münster. One I could understand but the other required more prolonged study than I was able to give.

At the Landesmusuem we acquired bicycles, a map and catalogue which actually had reproductions of the sculptures, so that you knew what you were looking for, which was just as well since some of them were disguised as bus stops or advertising hoardings, or hidden down wells or in the top of a tree. The biggest disappointment was provided by the Mystery of the Disappearing Hamilton Finlay. Finally, after prolonged search in a cemetery, we found two nails high up in a tree from which the Finlay plaque had been stolen.

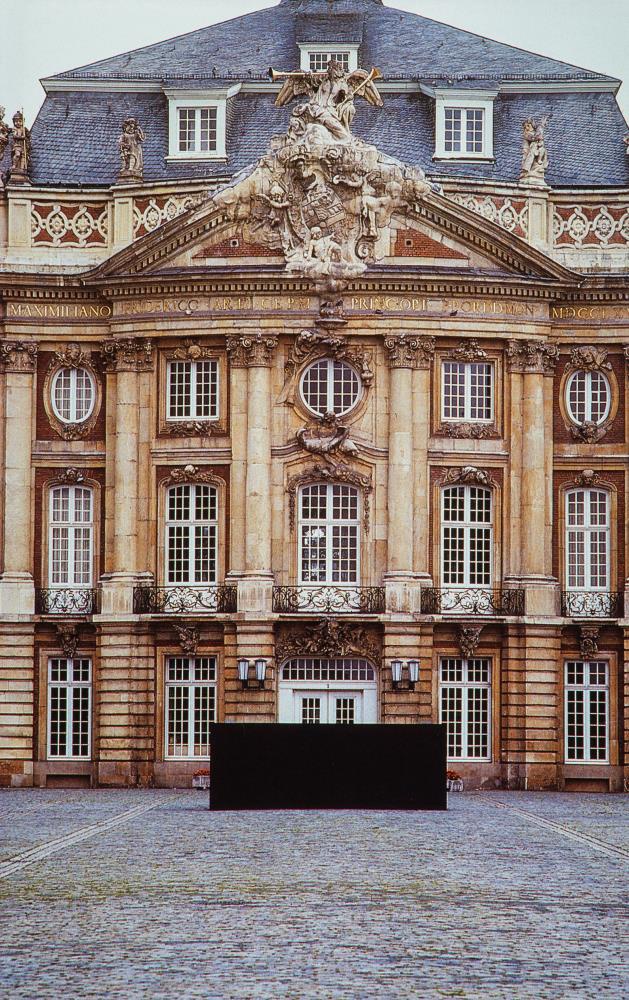

We bicycled, alternately exhilarated and terrified, the length and breadth of Münster, and, out of a possible 36 sculptures, tracked down 25, two of which had vanished, one a splendid snail-shaped Richard Deacon. Carl André had covered a tumulus with steel plates, Claes Oldenburg had provided three huge concrete balls which had been heavily defaced with graffiti, and Sol Lewitt a ziggurat and a large black box. The Per Kirkeby was hard to identify, since it resembled a brick air-conditioning plant and was unwittingly providing the centrepiece for a dressage contest. The most exciting installation was Rebecca Horn’s, in an old tumbledown tower. You entered a dark underground passage lit only by nightlights. As your eyes became accustomed to the gloom you became aware of sharp little hammers hitting the walls at unspecified intervals. I felt that I had stumbled into the caves of the Niebelungen. Emerging into the daylight one found an open space with a dark circular pool of water serenely reflecting the trees above. It was total theatre.

It was with a sense of triumphant achievement that we returned the bicycles and walked wearily to the station. It was not until the next day that the full extent of wear and tear, in the form of acute saddle-soreness, became apparent. I walked round the acres of Documenta bow-legged, like a retired jockey.

This article was first published in ArtReview September 1987