At National Gallery Singapore, a glimpse at a neglected piece of the island city-state’s art history

Boomers had it good, yeah? Well, not if you’re an artist in Singapore. Your career would have peaked somewhere between the 1960s and the 1980s, also known as the awkward period straddling ‘modern’ and ‘contemporary art’. Such labels may be woolly, but you still suffer from a lack of easy branding, unlike, say, the cohort before you, the ‘modern masters’, the China-born artists who migrated to Singapore and developed a local idiom melding Western painting and Chinese ink. And of course, after you are the sexy contemporary artists, the artworld’s default tribe.

This club of neglected middle children is finally getting some love in the National Gallery’s latest show. Perhaps acknowledging the difficulty of spinning a coherent overall narrative of this period, the gallery opted to have six individual retrospectives. The ‘after 1965’ timestamp refers to the year of Singapore’s independence, and the press release states hopefully that audiences would be able to ‘draw connections between the artworks and developments in Singapore’s history and cultural identity in the post-independence era’. Indeed, pinging through the showcases are certain recurrent ideas, such as the place of spirituality in modern life, cultural hybridity and technological change. Here, you glimpse the historical era through the artists. In most conscientious NGS megashows, it’s the other way round. In terms of art history, the exhibition also colours in some blanks. For me, it traces the precursors of certain tendencies in local contemporary art, such as the exploration of indigenous religious practices and arcana.

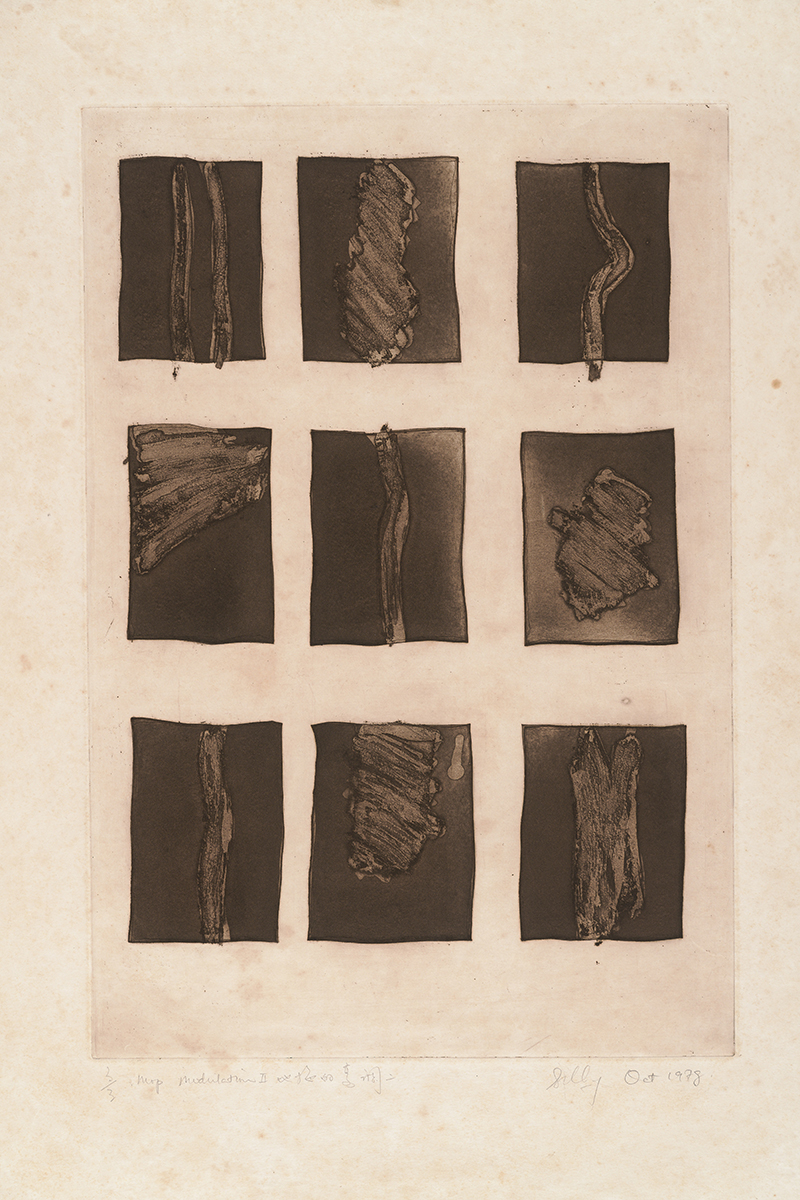

Opening the show is a moving survey of artist, writer and lyricist Chng Seok Tin (1946–2019), a stalwart figure who, before this, stands somewhat in the background of local art-history, but who never stopped creating even through disability and illness. Depending on her circumstances, she worked in different media. During the 1970s and 1980s, when she studied overseas, she was primarily a printmaker. Her surroundings fed directly into her etchings – the spare, wintry fields of Iowa and the riverine landscapes of Hull.

In 1988, a freak accident left her 90 percent blind. Out of necessity, she went into sculpture and installation, including pieces she made and remade over the years. The exhibition highlights some of these largescale installations, such as a chessboard with human figurines (Game of Chess, 1997–2001) and a mixed-media work interpreting the 64 hexagrams in the I-Ching (Variations on I-Ching, 1982–92).

Delicate works that draw from the everyday better show off her strengths. One such series is inspired by kim-chiam, or dried daylily buds, a traditional Chinese ingredient. These spindly vegetables are individually knotted, and their fragile forms become transmuted into tiny human figures in her art. As you leave the exhibition, one of the last works you see is the joyous Kim Chiam Code (2008), featuring these tiny vegetable-people she fashioned by touch alone, dancing and embracing.

Next up is a deep dive into Malay magic and esoterica: the showcase of artist, traditional healer, Sufi mystic and collector of Southeast Asian artefacts, Mohammad Din Mohammad. The exhibition is genre-bending, containing an almost equal mix of art and ethnographic displays. Art-wise, there are paintings and assemblages with intense mystical themes made from the 1990s to the 2000s. Then there is Mohammad Din’s collection of artefacts, including textiles, krises (traditional Malay daggers) and Islamic manuscripts.

Art and religion are two sides of the same coin. A pair of mixed-media works studded with bone, wood and shells (Earth Energy and Earth Energy II, 1994) are designed to be therapeutic, for the patients who looked at them in his house, and now, presumably, for anyone. A series of calligraphic works featuring the Arabic alphabet was painted with his bare hands using silat (a Malay term for indigenous martial arts) movements to channel his internal energy onto the canvas.

Was Mohammad Din a mystic-as-artist, or an artist-as-mystic? The curator doesn’t come down on either side, portraying his religiosity and art as one continuous world. In the paintings, I would say the mystic comes first. Often jejune compositions executed in bright colours, and heavy with straight-forward symbolism, they have more cultural- anthropological significance than aesthetic charge. In the assemblages, the professional artist is more obvious. The works are combinations of found objects that juxtapose the traditional and contemporary, the spiritual and mundane. Take the Franken-creature he calls The Singa Kuda – Alternative Vehicle (1996–99).

A horse’s skull and tail are attached to a computer stand, with a row of coconuts replacing its ‘body’. The whole thing balances on a piece of driftwood covered in horseshoes. At the legs is a Sundanese puppet and on its back a smaller Balinese lion. Cheerfully blending mythologies and cultural practices from the region, this vehicle is like some fabulous chariot from a Southeast Asian steampunk universe. Following Mohammad Din are three relatively conventional presentations. The first is a trek through Goh Beng Kwan’s career, tracing his journey from the 1940s to 90s, from early experiments in abstraction in New York to his return to Singapore, where local influences fed into his collages. Next comes the light and airy world of Eng Tow and her nature-inspired work in textiles and paper. Finally, there is the show of Jaafar Latiff ’s abstract batik works and acrylic paintings.

National Gallery Singapore.

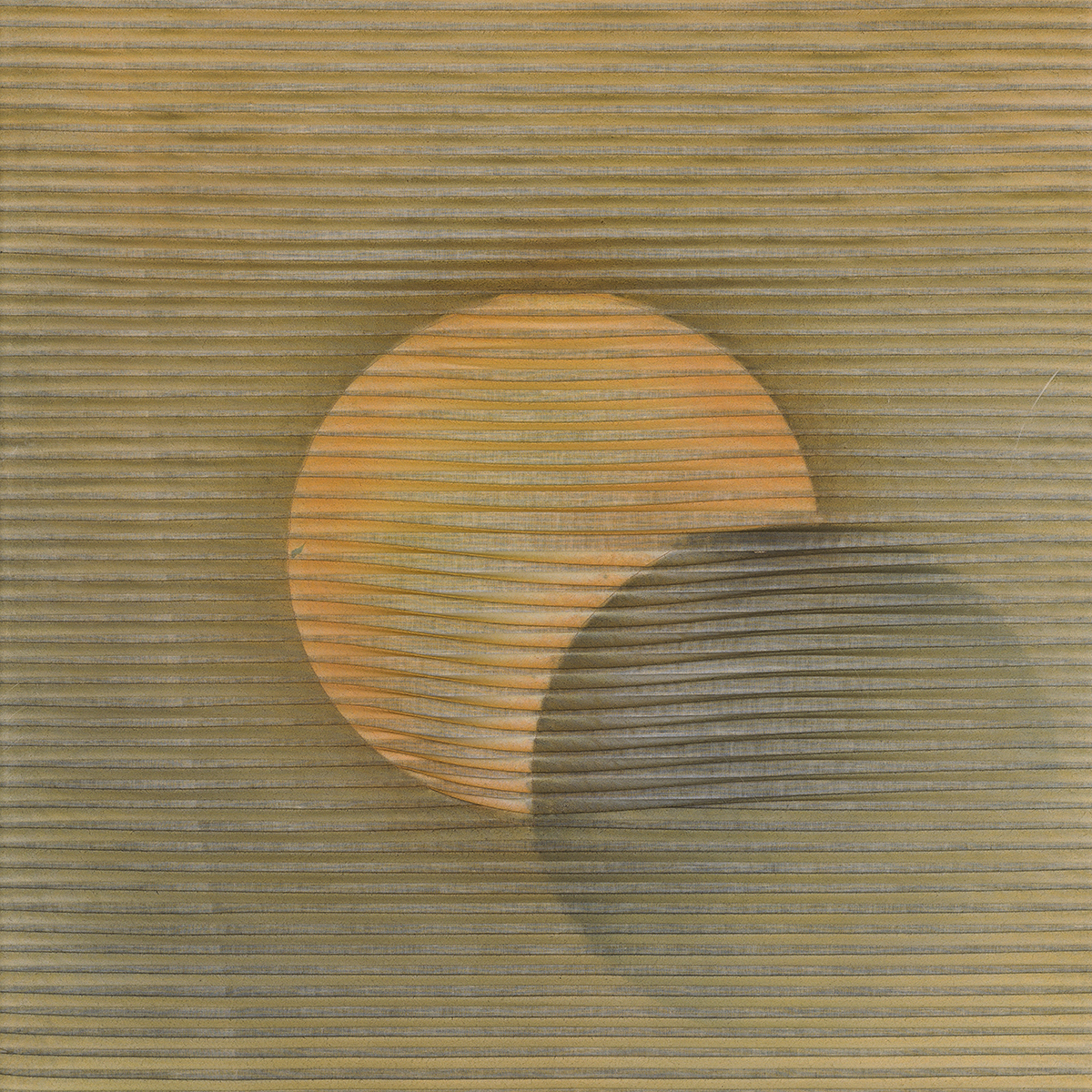

Finally, we go into mad genius territory. Enter Lin Hsin Hsin, artist, IT professional, poet, composer and uniquely wired person. She was big in the 1970s to 1980s for her abstract paintings, but moved into digital art and flew off the radar. Now she apparently works in cybersecurity and has scrubbed off most online references to her analogue work.

The exhibition focuses on her work from the 1970s to 1994, the offline back catalogue she seems to have disavowed. It’s a shame, because it is a weird and wonderful world that brings together grand cosmic themes

with technology. The gallery is dimly lit, like a planetarium, and the walls are painted black. Her luminous canvases appear to float. The works inspired by music, water and outer space are Miró-esque compositions that generate a soft, gravity-free environment, including ‘harder’ subjects like computers and software, which were a great source of inspiration for her during the 1970s and 80s.

The last room brings us up to the present and concentrates on her recent digital artworks, whose processes I’m too stupid to understand. In here are prints of butterflies rendered by equation, patterns generated by algorithm and a section of a 1.8km landscape whose size she managed to crunch via some computer magic. There you go: here’s a boomer artist who is more postinternet than you. But that is probably a story for another time.

Something New Must Turn Up: Six Singaporean Artists After 1965 at National Gallery Singapore, 7 May – 22 August

From the Summer 2021 issue of ArtReview