The artist’s central project, 37 years and counting, is a dialogue with himself about the collapse of the image. Why does this matter so much?

If contemporary art today often appears to lack stakes, seems overdetermined or too thoroughly codified, or otherwise feels unresponsive to the moment, it might make some sense to turn to the recent past, to the last time things seemed this way. Stephen Prina graduated from CalArts in 1980, at another time in which it appeared as though the discursive system of art had run out of road. Conceptual art was already history, he has said, and the extensive changes the artworld underwent over the following two decades had yet to take hold. It was in this context that Prina, alongside a number of other artists belonging to CalArts’ second generation, began to contribute to a burgeoning form of practice the artist and critic Coosje van Bruggen indelibly defined as ‘impure conceptual art’.

An early postmedium artist par exemplar, Prina studied visual art in tandem with musical composition and never expected to choose between the two; his practice has come to encompass sculpture, painting, video, sound and performance, often exhibited alongside one another within installations, projects that are frequently restaged, reworked and reconsidered over time. Artists may not necessarily think in terms of problems and solutions, but if Prina devised a workaround to an ambient sense of malaise, it was this: to build a semiautonomous system of ideas, strategies and references on speaking terms with the broader workings of the art system, but more often, more eagerly, willing to talk to itself.

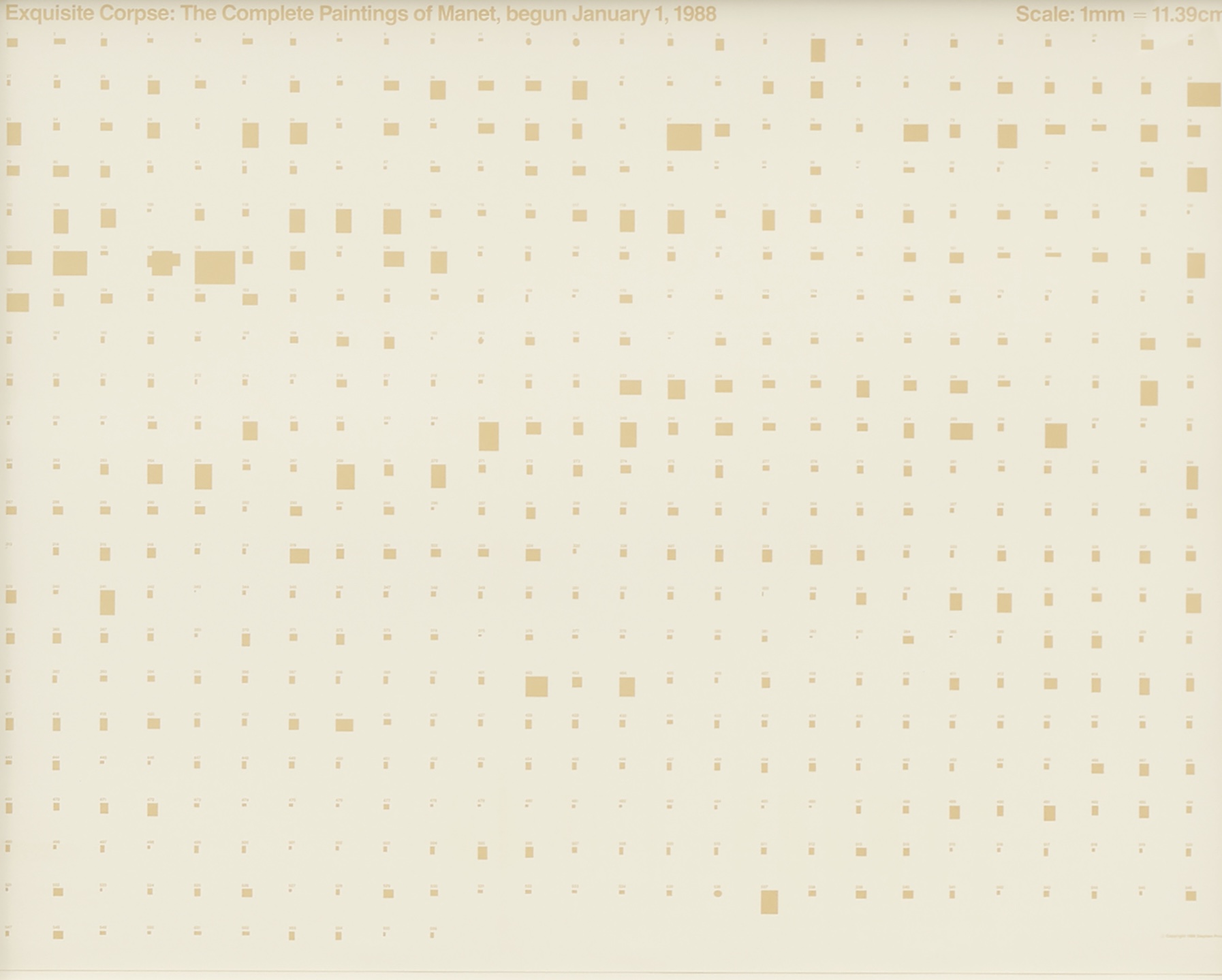

This body of work has been structured around Exquisite Corpse: The Complete Paintings of Manet (1988–), which Prina initiated on New Year’s Day of 1988 and has contributed to periodically over the past 37 years. Conceived as a lifelong project, Exquisite Corpse proposes to remake, or perhaps diagram, the 556 paintings of Manet’s corpus as they appear in a 1969 edition of The Complete Paintings of Manet, a sort of mass-market catalogue raisonné published by Penguin Classics of World Art. For each work within the project, Prina replicates the dimensions of a given painting and retains the work’s paratextual information (title, date and provenance). What he jettisons is the pictorial composition – the image – substituting it for a wash of sepia ink applied to rag paper, cut to proper size. Each ink painting is housed in a black gallery frame, and when several are installed together, the works become nearly spectral, suggesting a museological display exorcised of subjective content.

If we are indeed to interpret Exquisite Corpse as ‘ghostlike’, as some critics have suggested, it might also be said to condense, mournfully, a particular history of modernism catalysed by Manet, in the conventional understanding, and supplanted by Conceptual art. In this reading, The Complete Paintings of Manet is not only the cheap paperback that happened to sit on Prina’s bookshelf, but also a highly specific reference. Printed in 1969 – the same year as the inaugural issue of Art-Language: The Journal of Conceptual Art, a sort of ur-text for contemporary art, and the influential Michael Fried essay ‘Manet’s Sources’ – the intermediating book already points us towards the passage from formalist-modernism to an information-based system of artistic production. Drawing upon the theorist Peter Osborne and others, one might also suggest that the image, the foundational element of Western art in the Judeo-Christian tradition, was twice negated in the twentieth century: first by modernism’s progressive tendency towards abstraction, and then later by its conceptual turn. Exquisite Corpse collapses this double negation into a single project, one that recurrently haunts or witnesses the remainder of Prina’s oeuvre.

Unlike many of his generational cohort – his friend and collaborator Christopher Williams, for instance, but also Ericka Beckman, Tony Oursler or Carrie Mae Weems – Prina never really embraced the image or its resurgence in the latter part of the twentieth century. A Guy Debord-style critique of mass media never fully materialises either, although popular culture trickles in from odd angles. References, both extrinsic and reflexive, run the line from the erudite to the vernacular, spin out, go crazy. An ostensibly autobiographical installation, galesburg, illinois+ (2015), centred around the artist’s Midwest hometown, occasions an opportunity to triangulate the works of fellow Galesburg natives Dorothea Tanning, the Surrealist painter, and Carl Sandburg, the poet and Lincoln’s biographer, with the Harbor Lights Supper Club, a defunct restaurant in which Prina performed music while in his early twenties. For Monochrome Painting (1988–89), closer to Exquisite Corpse, Prina borrowed the 14-panel configuration of Barnett Newman’s Stations of the Cross (1958–66), and applied it to a hyperbolised canon of the monochrome, remaking works by Kazimir Malevich, Yves Klein, Ad Reinhardt and Robert Ryman, among others. Again replicating a chosen work’s dimensions while exchanging its imagistic content, he covered each panel in automotive paint, in Papyrus Green polymer, a shade of teal briefly produced by Volkswagen in 1985. A similar logic informs As He Remembered It (2011), in which Prina coated R.M. Schindler’s inbuilt furniture, emblematic of Californian modernism, with a thick layer of Honeysuckle Pink, another strangely specific hue, Pantone’s 2011 Color of the Year. In both instances, the present conceals the past, although the inverse occasionally holds true as well. In a series of collaborative exhibitions with Wade Guyton, staged at Petzel in New York between 2010 and 2019, Prina defaced Guyton’s signature diptych canvases with the same gesture, a spot of black spraypaint applied to the top-left corner of each painting. Rather than an arbitrary act of (artist sanctioned) vandalism, this gesture was, in actuality, a repetitive recreation of Prina’s earlier piece Push Comes to Love (1999), which, in turn, had been a deliberate misreading of a 1968 directive issued by Lawrence Weiner: ‘TWO MINUTES OF SPRAY PAINT DIRECTLY UPON THE FLOOR FROM A STANDARD AEROSOL SPRAY CAN’.

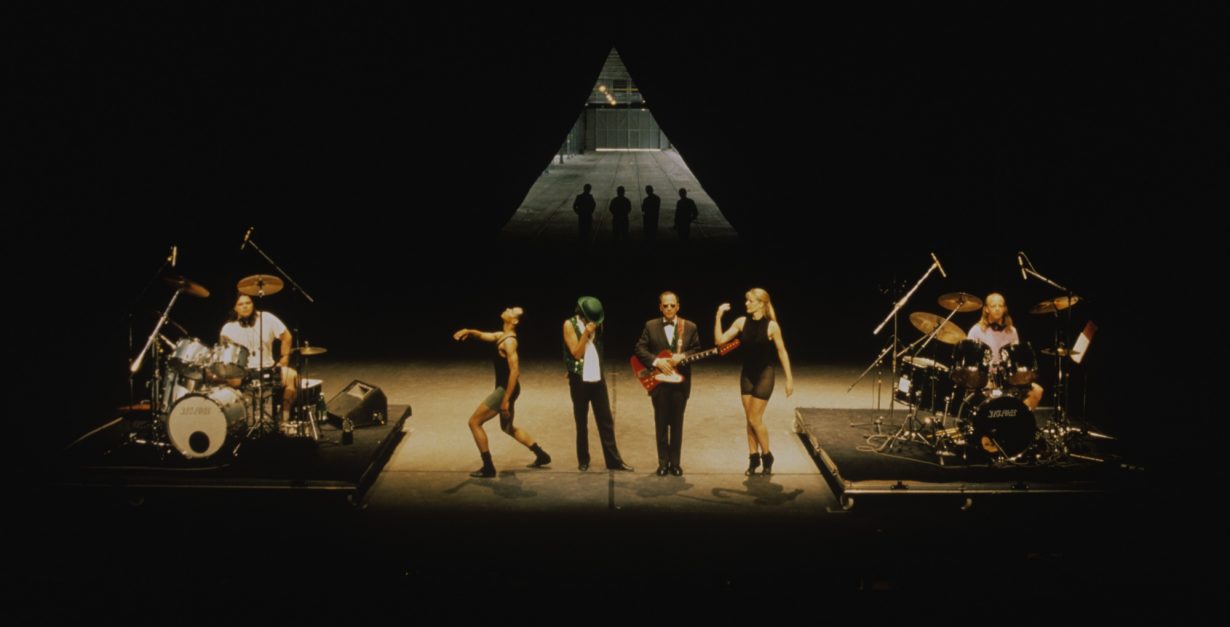

During the early 1990s, performance began to reenter Prina’s practice through the backdoor of pop music. Throughout the preceding decade, the signal interference of pop had already been percolating beneath the surface of earlier works and had begun to emerge as an unsettling counterpoint within Prina’s relatively austere installations. Successive iterations of the early work Aristotle-Plato-Socrates (1982), for example, culminated in The Top Thirteen Singles from Billboard’s Hot 100 Singles Chart for the Week Ending September 11, 1993 (1993), a wall clock that plays then-ubiquitous songs like Mariah Carey’s Dreamlover on the hour. Yet Prina attributes the introduction of such pieces as Sonic Dan (1994–2001), a combinatory rendition of songs by Sonic Youth and Steely Dan, and Beat of the Traps (1992), a collaboration with Mike Kelley and Anita Pace, to a karaoke party at which Kelley and Liz Larner competed with one another in a wilfully bad duet. It’s here that Prina may have intuited an analogy between the professional artist and the pop star and realised that his aversion to becoming a public-facing subject, inherited from his professor, the American conceptual artist Michael Asher, may have required some recalibration. One suspects that Prina’s turn towards performance formed a response to a body of work that had grown too hermetic, too insular. After all, there may be limits to talking to oneself.

In this regard, it’s difficult not to think of an oddity in the Prina oeuvre: the solo album Push Comes to Love, released by the label Drag City in 1999. Composed of gentle indie-pop songs, the album features original music by Prina set to lyrics written by a cast of others, including Dennis Cooper, David Grubbs, Mayo Thompson and Lynne Tillman. The music sometimes recalls The Magnetic Fields, sometimes Tortoise, and occasionally Prina’s solitary voice lilts like Morrissey’s. The album recommends a Prina free from the constraints of his lifework, liberated from the confines of his own making: it is more directly queer, more openly social, less burdened by the sweep of history. But of course this momentary detour from the art system was only that, a detour. In the same year, Push Comes to Love appeared again – as part of an installation, as a compact disc on display at Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne. No longer an outlier, yet once more situated within the expansive Prina system.

Stephen Prina: A Lick and a Promise is on view at MoMA, New York, 12 September – 13 December

Jeremy Gloster is a writer based in New York

From the September 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.