The conceptual and performance artist on coming of age in a rapidly changing Korea

When Sung Neung Kyung entered college in 1960s South Korea, Art Informel and Abstract Expressionism were all the rage, and the artists associated with Dansaekhwa had begun to come into their own. By the time he finished his studies and military service, the scene was blossoming with alternative groups pursuing conceptual and dematerialised practices, including Space and Time (ST), which artist Lee Kun-Yong invited him to join in 1973. Sung would go on to bring newspapers and often prosaic actions into the field of art, slyly responding to the political climate in the country: dictator Park Chung-hee imposed martial law in 1972, and artists had to negotiate a regime at turns surveillant, censorial and supportive (when the overseas artworld showed interest).

Like many of his performance- and concept-oriented peers, Sung is late to receive international acclaim. ArtReview Asia was lucky to speak with him as he prepares for solo exhibitions at Gallery Hyundai, Seoul (through 8 October), and Lehmann Maupin, New York (2024) – and as many of his early works travel from MMCA Seoul to the Guggenheim, New York, in the exhibition Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s (through 7 January).

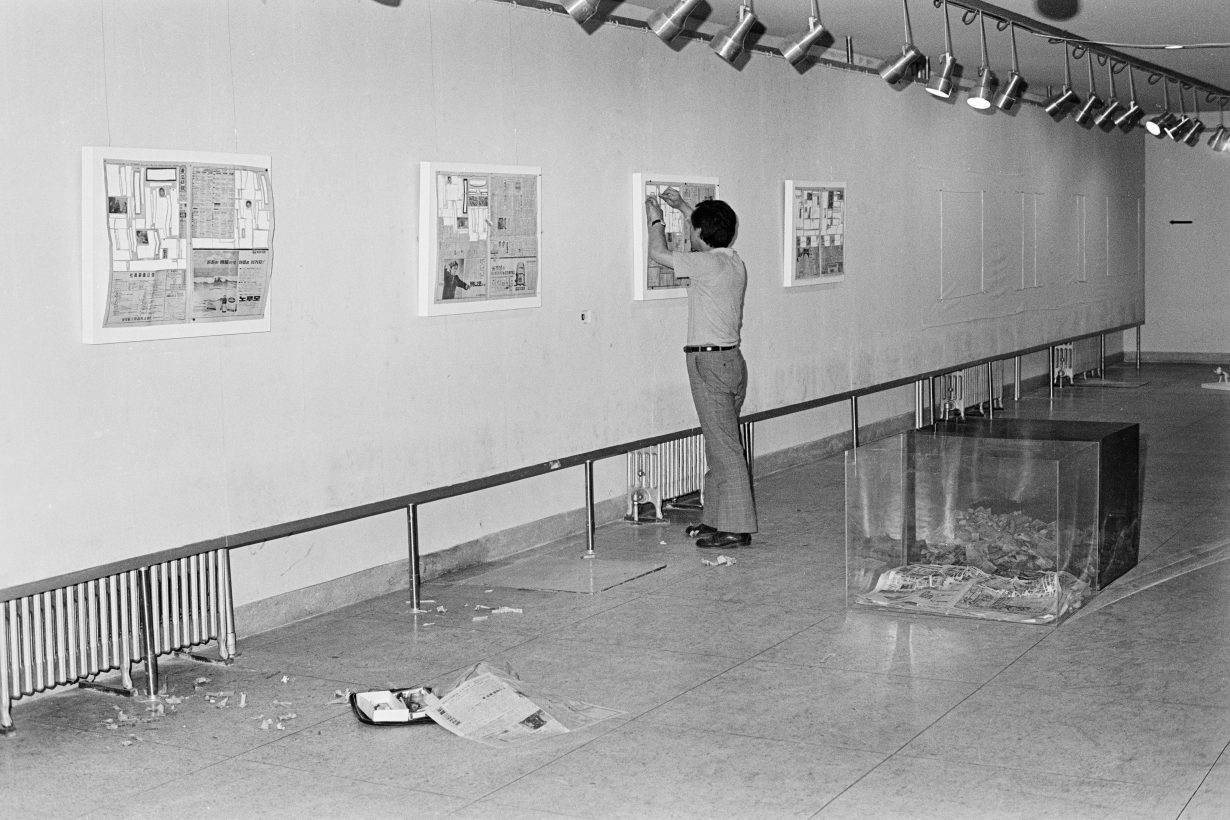

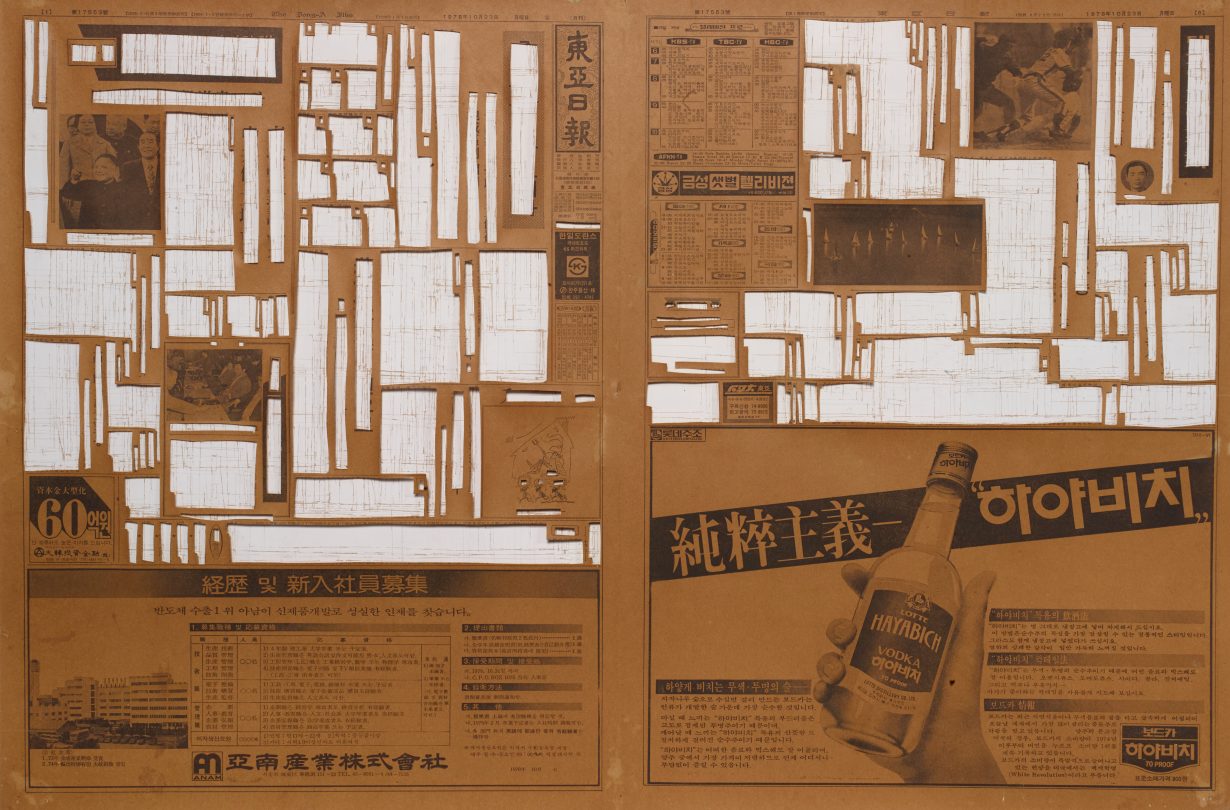

ArtReview Asia One of your significant early works was Newspaper: from June 1, 1974, on [1974]. As your contribution to a weeklong exhibition held by ST, you attached parts of the day’s newspaper to panels on the wall, cut out all the articles and deposited the scraps in a blue acrylic box. The following day, the skeletal newspapers went in a clear acrylic box, and new ones were cut. Can you talk about how the project took shape?

Sung Neung Kyung This was a way for me to provide commentary about the very difficult political situation in South Korea. But if I think back to those actions, they don’t seem that effective. They were more like mosquito sounds: very small noises against brutal political oppression. Maybe I lacked enough courage at the time.

As you mentioned, I was creating blank spaces by cutting out newspaper articles – and trying to identify the potential meaning or significance that could have existed there. Only the photographs and advertisements were left. This was the starting point for all of my later work in photography, performance art and installation.

ARA Your transition to photography was almost immediate! That same year, you purchased a Nikon F2 and began staging actions for the camera, which were later exhibited as sequences of prints. Many of these works depict everyday gestures like eating an apple [Apple, 1976] and smoking a cigarette [Smoking, 1976].

SNK Smoking just documents an action, but if you think about it, that action was a common denominator that tied everyone together – working-class folks and higher-ups. At the time, Park Chung-hee was known to smoke five packs of cigarettes a day, and I would also smoke that much sometimes. I guess this was one act of true freedom granted to us, and it was the one act of true freedom we shared with the dictator.

That said, I want to emphasise that I have since given up smoking!

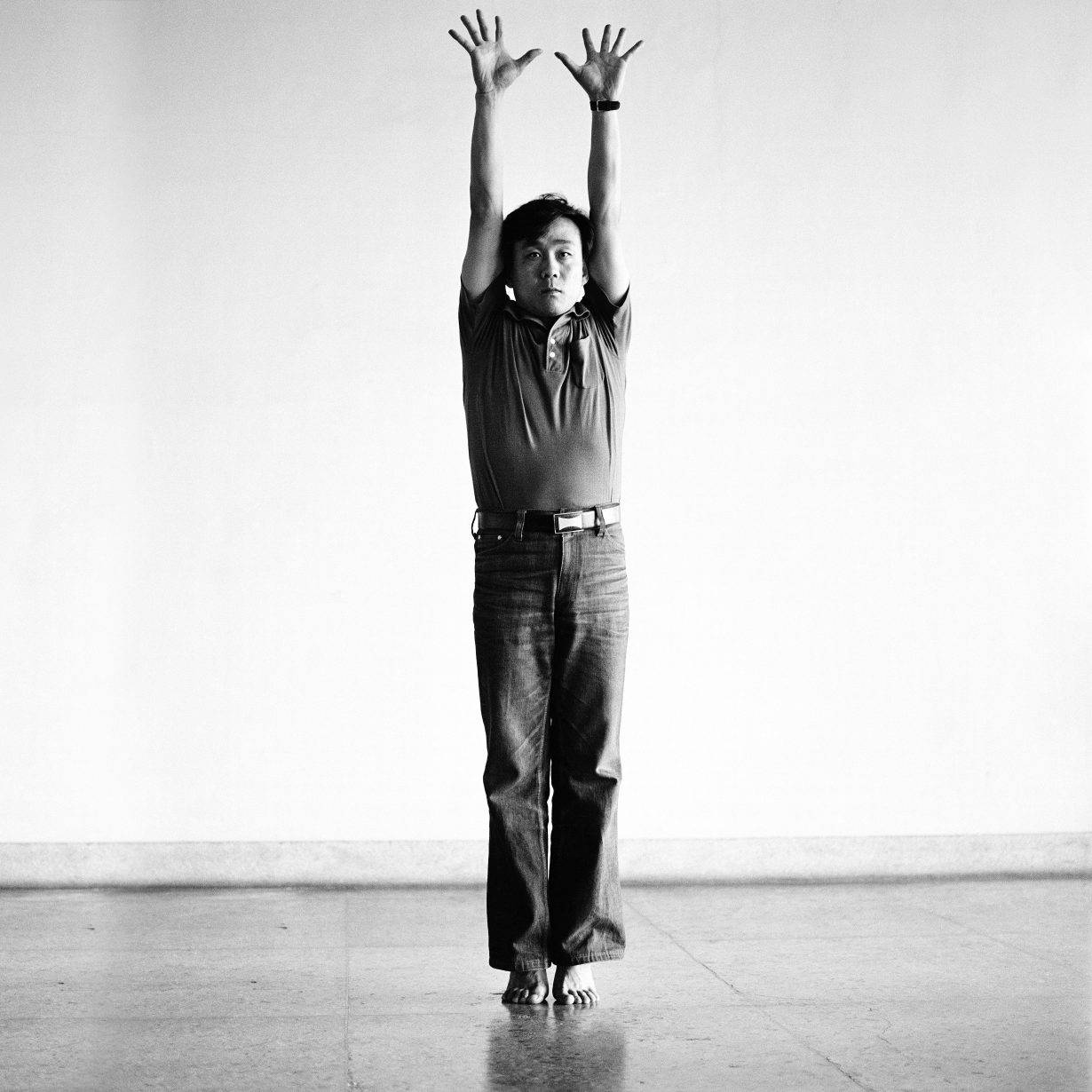

ARA Of your photographic work from this era, I’m particularly curious about Contraction and Expansion [1976], a series of 12 photographs in which you raise your hands, lie on the ground, then spread them again.

SNK I had started working with conceptual art and using my own body as a vessel to express myself. Contraction and Expansion really began with asking myself: what is my body? What is this physical being, this mass I have?

I think we can broaden the significance of this piece because at the time in South Korea contraction could refer to how political power represses the expression of individuals, whereas expansion allows them to express themselves. These countervailing forces are acting together in this work.

ARA There’s an interesting play of agency in Contraction and Expansion. While you’ve staged this action for the camera, it looks like you’re following the commands of some external authority. Your hands shoot up, your eyes widen, your body reacts. I’m reminded of stories you’ve told from this period of martial law: that your hands trembled when cutting newspapers in the gallery, and your voice shook during reading performances. Power found subtle ways to reverberate through the body.

As Jeff Wall has noted, for photoconceptualists of this era, documenting performances – even when conducted alone in a studio – had the quality of reportage. This link becomes even stronger considering your work with newspapers: the image, beyond its aesthetic merits, is a channel of information and the product of authorial and editorial intent. We can see this in your Venue series, which you commenced in 1979.

SNK At the time, power was like an omnipotent god. Power existed above everything else. This is to say that other opinions simply could not exist. We could not even think about the possibility of two-sided communication like the kind we have today. There was only a one-sided circuit.

The Venue series is tied to this. It was inspired by my reading of newspapers. South Korean newspapers in particular use a lot of symbols – small circles and triangles and lines and dashes – that point and direct the reader’s attention to where the editor wants them to look. I chose to present an alternative opinion to editorial authority – opposition to this unilateral communication circuit. In my mind, editorial power and political power were very similar.

ARA You’d often double the editorial symbols by applying ink to film. Many of the resulting prints have become part of massive installations.

SNK I tried to do this for my first solo exhibition in 1985 [Venue, Kwanhoon Gallery, Seoul] when I used 1,500 different photographs. I wanted to create a parade for the public: a look at recent history and the contemporary moment through images. Since then, the Venue series has been exhibited about 40 times in different ways.

ARA I’ve heard that Venue 6 [1981] was inspired by the story of a young North Korean guerrilla.

SNK Yes, it came from a sense of compassion for the guerrilla. He crossed the border, was shot and killed, then North Korea denied ever sending him. The guerrilla was denied by his own country, and he died on our soil, though he’s not South Korean. We know he’s Korean, but this is a man without citizenship.

Venue 6 was an attempt to offer my condolences to this young boy and keep his memory alive. I imagined, if he had safely made it to South Korea, what would be the arc of his travels through the country? What route would he have taken? This is what I tried to express through the dotted line.

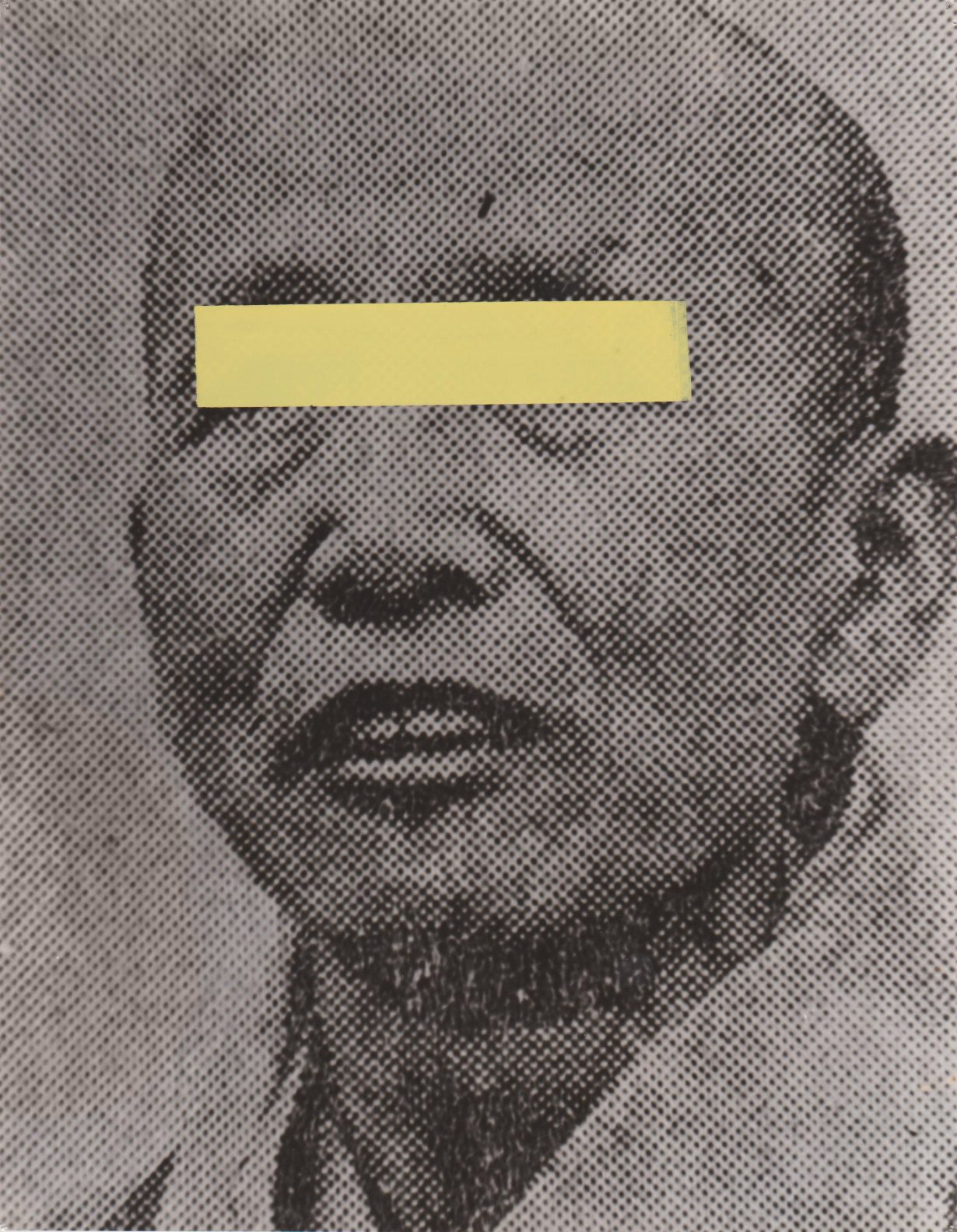

ARA There’s something rather intimate about this work that makes me think of S. at Mid-Life [1977], where you enlarged 15 images from your personal photo albums. This work marked the beginning of several autobiographical projects spanning more than 30 years, including snapshots of your children [S’s Posterity: Botched Art is More Beautiful, 1991] and strobe-lit photographs of your home [The Shadow of Delirium, 2001].

SNK I was thirty-five when I worked on S. at Mid-Life, and I thought that maybe I would live to seventy at best. That explains the title. I took images from elementary school, my college days and my period of military service.

In the South Korean artworld of the time, people talked about ‘grand narratives’ and ‘world narratives’, but I wanted to create a micro-narrative: something personal in nature. I also wanted to propose the idea that ‘the artist is dead’, which is why my eyes are blacked out.

ARA You silkscreened bars over them – a convention of some newspapers that you’ve explored in other works like No relationship to a particular person 1 [1977]. It seems you were trying to shift focus to the other characters in the scenes.

SNK Some audience members used coins to try to scratch the silkscreen off the images. With that, I guess the artist was reborn. The artist returned.

ARA Cathy Park Hong has observed that ‘English is our ever-expanding neoliberal lingua franca… The more developing the nation, the more in need that nation is of a copy editor.’ I couldn’t help but connect her quote to Everyday English [2004–18].

SNK This began as a hobby and slowly evolved into an art piece: learning some English using the ‘English Review’ pages in the daily newspaper I subscribed to. You have to bear in mind that this was not business English. There would be conversational, casual, informal words here and there – and maybe some borderline slang. There were times when I was a bit lazy and didn’t complete the reviews, but all in all, there are about 3,000 works, which I curated down to 2,700.

One of my objectives was to prove to myself that I was still an artist through this daily activity. Because I’m also a performance artist, I wanted to do something performative every day.

ARA Though decades have passed since the political climate that informed your first newspaper work, I am struck by some echoes. Everyday English has partly coincided with the presidency of Park Geun-hye [2013–17], whose term included the reinstating of state-issued history textbooks and a notorious cultural blacklist. While the conditions were incomparable to those under her father, Park Chung-hee, it’s an example of the potential backslide of even hard-won democracies.

I’m happy you mentioned performance, as I wanted to ask about it. Joan Kee has an interesting interpretation of South Korean performance under martial law: works involving ‘daily activities that most people did and could do’ helped ‘viewers think actively and consciously about life as something they practised, rather than as a status or a condition over which they had no control’. Examples could include the aforementioned image sequences of you eating an apple and smoking. Since the 1990s, you’ve developed a new strain of performance work that hybridises various, sometimes everyday activities in totally wild ways.

SNK My thought process during the 1990s was that I’m going to leverage everything I find interesting from Eastern and Western practices, contemporary and old. For instance, in one performance piece, I used prayer texts that are read aloud during Korean ancestral rites. There’s a way of chanting the texts, and I would shift between that and how Catholic priests chant during mass. Both have a singsong quality, though with different nuance.

ARA Your performances are also known to have saltier content, like urination and masturbation, and moments when you engage audience members by sharing a snack or slinging ping-pong balls at them.

SNK My methodology involves looking for things that are not yet art and turning them into art. This content is not limited to masturbation, or eating a snack, or picking your teeth, or hitting somebody, or giving a blessing. Anything from my everyday life can be incorporated into my performance art.

It’s almost as if my performances are composed of different joints or modules that connect. Links in a chain. Keys on a piano. Blocks of Legos. Bring them together, and they create a whole.

I could describe myself as a ‘module performer’: I own nothing of my work, nothing is originally mine. I’m just building modules.

ARA In recent performances, you sometimes speak what you call ‘one-line manifestos’. I particularly like your manifesto ‘Art is easy, life is hard’. What does this mean to you?

SNK Life is very difficult sometimes, and compared to its challenges, thinking about art comes so easily to me. It’s hard paying the bills, putting food on the table. Art is number two – it’s the second priority.

Tyler Coburn is an artist, writer and teacher based in New York. Interpretation from Korean provided by Amber Hyun Jung Kim