What does Tongchua want us to see about the Thai nation-state in his glowering pitch-black pinnacles and serrated lines?

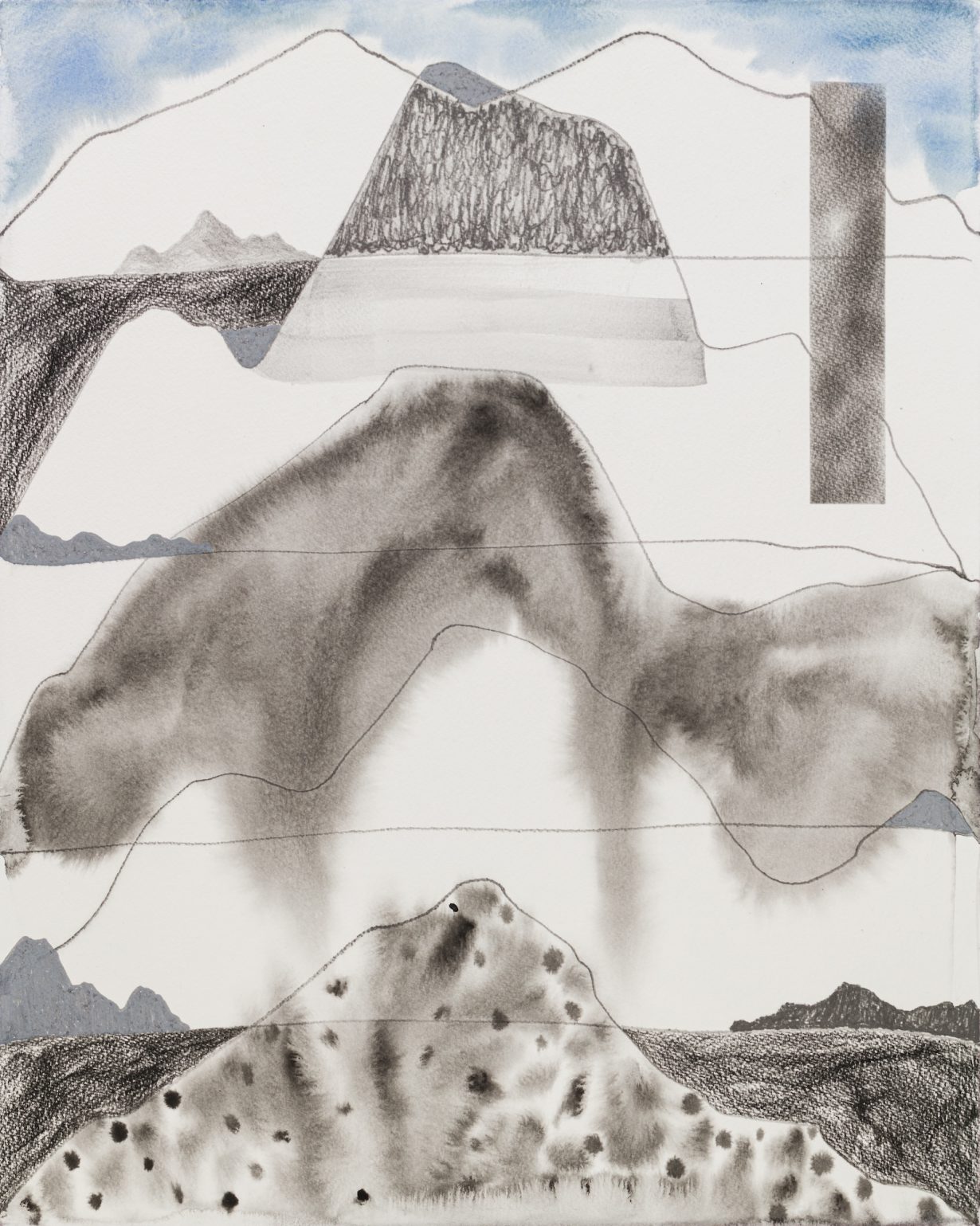

Surajate Tongchua has a habit of repeating himself. Spread across two floors are mountain studies – 70 or so of varying size – rendered in achromatic mixtures of pencil, black ink and grey paint on handmade mulberry and bamboo paper. Hung on freestanding wood frames as well as walls, these mixed-media drawings (all Lying Mountain, 2022–25) could pass for geological field sketches, albeit ones executed by a dreamy student more interested in the Platonic higher realm of mountains, mountainness, than recording them in nature. In each drawing, floating mountains hover (sometimes wonkily, sometimes upside down) in barren skies amid other floating mountains, vaporous layers of rock and roiling cloud banks. Meanwhile, at an overlapping show at Neu Contemporary in Bangkok (There are only Color and Mountain), Tongchua’s mountain fetish has also found an outlet in popping acrylics – semiabstract paintings individually themed around a single colour (red, green, blue, orange or yellow). In these more anarchic works, amorphous blocks of pure or mottled paint fold around one another, creating psychedelic patchworks of hills and peaks.

Tongchua’s mountainscapes are referential as well as recursive. With globules of watery ink and negative space dominating some of the works at Panic Room, their debt to traditional Chinese ink painting feels especially strong. But while the artists of the Song dynasty often (but not always) extolled, or idealised, the virtues and harmony of their society through mark-making, Tongchua is interested in questioning his: these mountains ‘reflect the pressure, ambiguity, and oppressive atmosphere created by authoritarian systems’, he pontificates in the wall text.

To say there’s a whiff of social critique here would be an understatement. Alongside late-eighteenth-century Romanticism, the title and wall text also invoke Akira Kurosawa’s film about the elusiveness of objective ‘truth’ amid conflicting testimonies (Rashomon, 1950); political philosopher Thomas Paine’s rousing pamphlet railing against monarchal rule in British America (Common Sense, 1776); and the active, accusatory tone of ‘lying’ (which, in a few works, becomes a motif that is faintly block-printed, over and over, to form the body of a low-level cloud or soillike texture). As if this were not enough rationalisation, Rashomon on Lying Mountain also plants localised associations in the audience’s mind, including the air pollution problem in Chiang Mai: ‘a direct consequence of irresponsible power-driven policies and the elite’s exploitation of natural resources at the expense of local communities’, the wall text states. And on one small drawing, the phrase ‘power can corrode every day’ appears.

On one hand, this is fecund, and well-travelled, terrain. Beyond its supra-cultural associations – with mystique, with strength, with the insurmountable – the highlands of the Thai kingdom are intimately bound up with land rights, slash and burn farming, royal development projects and communist history, among other divisive and knotty topics. Moreover, the smog problem – which is directly referenced on the second floor, where sheer curtains printed with digital manipulations of the surrounding drawings cast a grey pall over the windows (Visiting Neighbor in the Summer, 2023) – has caused considerable chagrin among Thai artists in recent years.

On the other hand, I’m not sure pointing the audience down paths of meaning so assiduously is necessary. While Tongchua wants us to see commentary vis-à-vis the Thai nation-state in his glowering pitch-black pinnacles and serrated lines (the more insistently you look, the more of a shaky construct, the more unsolid and volatile, it reveals itself to be, or something to that effect), his mountainscapes are at their best when we approach them as such – when we remember that landscape gains its power through conscious apperception, not superimposed narrative (colour-coded Thai politics, in the case of the Bangkok show).

Which is to say that treating these works like flashcards in a projective test, wallowing in their preternatural gloom and unearthly gravity – simply looking at the view – proves more rewarding than trying to parse their draughtsmanship, facture or mood using the terms supplied. The wonky physics and inhospitable topography, the smooth shading of the geological stratum, the contrast between substance and emptiness: these tirelessly reiterated elements create atmospheres that are sensed rather than deciphered. Consequently, the real thrill, and truth, of Tongchua’s repetitions lies in the immediacy, modularity and implied materiality of his destabilising scenes – in traversing the worlds within his drawings, not trying to tether them to the world outside.

Rashomon on Lying Mountain at Panic Room, Chiang Mai, through 27 July

From the Summer 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.