Tan Zi Hao’s pronounced linguistic distortions around the subject of race relations in Malaysia pose broader questions about the nature of ‘identity’ in a translingual culture

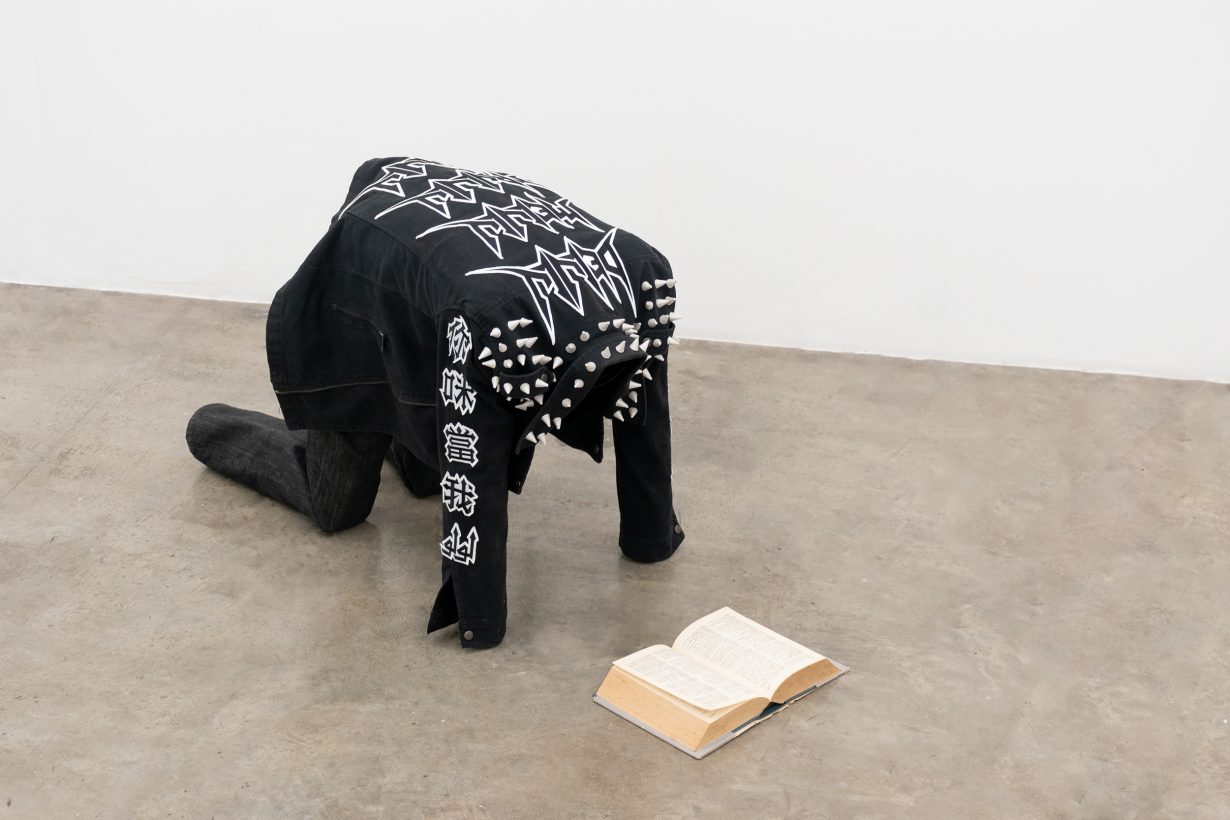

A figure manifested only by a black denim jacket and black jeans is on its knees, bowing down in front of a Malay dictionary that lies open on the floor. Patched onto the back of the jacket are the words DELULU, MELULU and TRULULU, rendered in the near-unreadable jagged spikes of a death metal font. This is Anthropophagic Strategies II (2024), one of Tan Zi Hao’s most recent works. In Gen Z internet-speak ‘delulu’ means delusional (in a positive, self-confident way), ‘melulu’ means reckless in Malay and ‘trululu’ is a derivation of delulu, meaning true. Running down the sleeves of the jacket is a Malaysian-Cantonese phrase, ‘你咪當我lulu’, which was popularised during the 1990s and means ‘don’t treat me like an idiot’. Also painted onto the jacket is the word ‘lulu’, inscribed in Jawi as ولول .

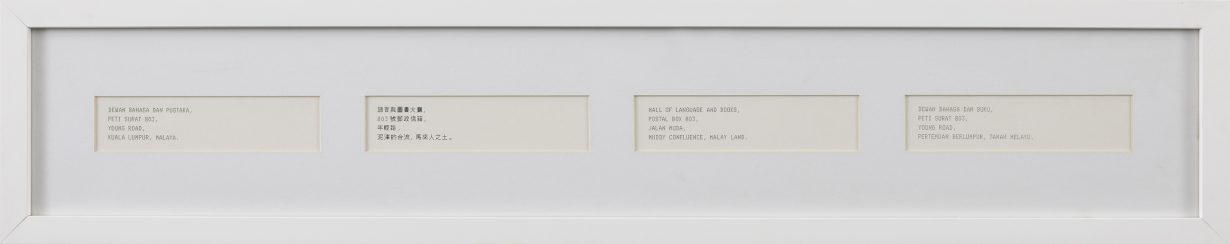

The morpheme ‘lulu’ takes a translingual journey in this work, its meaning changing through various slangs, slogans and scripts – although all of the word’s significance is centred around misperceptions. You could say that Tan’s multidisciplinary practice as a whole is invested in such crosslinguistic journeys, playing with translations and transliterations, and revelling in the intentional and unintentional mishaps that ensue. For example, Addressing the Institution (2018), a series of minimalist paper works that feature printed text, plays on distortions in the translation of the office address of the Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (Institute for Language and Literature), which is the government body responsible for coordinating the use of the Malay language and Malay-language literature in Malaysia. The address is translated from its original language (Malay) to English, and then back to Malay. All three versions of the address appear in the work. The Malay address, ‘Balai Pustaka, Bukit Timbalan, Johor Bahru, Malaya’, becomes ‘book hall, deputy hill, new hill, Malay land’ in English. Translated back to Malay, we have ‘Dewan buku, Bukit Timbalan, Bukit Muda, Tanah Melayu’.

Multicultural and multilingual ‘Malaya’ has become ‘Tanah Melayu’, the Malay homeland, a politically sensitive term used to denote the predominance of Malays in the country. What Tan, who is ethnically Chinese, highlights is the weight carried by the Malay language, synonymous with Malay ethnicity and ‘Malaysianness’ in general; an influence that is deeply felt by the country’s minorities.

Understanding the history of race relations in Malaysia sheds important light on Tan’s work. The Malays have long claimed a distinct position in Malaysia due to their longer history in the country. The British colonial administration incorporated the Malay monarchy into the independent Federation of Malaya in 1948, and Malays remained politically dominant after Malaysia achieved independence in 1963. Following this transitional moment, as the Chinese became increasingly influential from an economic standpoint, and demanded more political representation, racial tensions within the country began to simmer. When two newly established Chinese opposition parties won seats in the Malaysian Parliament in 1969, the victory sparked a Sino–Malay race riot that took place in Kuala Lumpur. The 13 May incident left as many as 600 dead.

An affirmative action programme followed that strongly favoured Malays. The New Economic Policy (NEP) was introduced as a means to reduce racial tensions and in place for two decades before being replaced by another comparable policy. Under the NEP, Malays and Indigenous peoples are classed as bumiputera (‘sons of the soil’) and have privileges in higher education, public sector employment and equity and property ownership. As of July 2023, 70.1 percent of the Malaysian population were classified as bumiputera, 22.6 percent were classified as ethnically Chinese and 6.6 percent as ethnically Indian. Many of these policies remain in effect.

Tan’s entry point into broader discussions about race is through language. First, he interrogates Malaysia’s racialised national language policy, which is inextricably linked to ethnonationalist thinking about how Malaysian national identity is constructed; second, he celebrates the more syncretic, idiosyncratic uses of language on the ground. Malay is designated the national language (the medium of instruction in national schools and in which all official documents are written), while English comes second. Only two main minority languages, Tamil and Chinese, are permitted as the medium of instruction in vernacular schools. Tan’s early works deal with the exclusion of minority languages in the country’s construction of national identity. In the 2014 video Negaraku. Bukan. My Country. Is Not. 我的祖国。不是。எனது நாடு. அல்ல. ਮੇਰਾ ਦੇਸ਼. ਨਾ. Menuaku. Ukai. Pogunku. Au. نڬاراکو, he overlays black-and-white footage of the National Day Parade in 1957, the year of Malaya’s indepenence from British rule, with translations of the Malaysian national anthem in eight languages, including non-official languages such as Iban and Kadazandusun, dominant in Malaysia’s Borneo states, Sarawak and Sabah. The archival images of this historic event are almost obscured by the wall of text.

Later, Tan became more interested in destabilising essentialist connections between a language and other identity markers, like ethnicity or nationality (reflective of a view that many progressive Malaysians share: few people would oppose Malay as a national language if it wasn’t so closely associated with the supremacy of any one ethnic group). His installation The Mercurial Inscription (2022) comprises a video animation that renders a key historical artefact in Malaysia, the 700-year-old Terengganu Inscription Stone, which can be seen floating in space, as well as an aluminium sculpture that is positioned in front of the screen: an imagined version of the stone’s missing part. Its inscription, acknowledged as the earliest example of Jawi writing in Southeast Asia, announces Islam as the state religion of Terengganu, an ancient sultanate, marking the initial establishment of Islam in Malaysia and the region more generally.

Visitors are invited to touch the sculpture, which subsequently activates the video, and the Jawi inscription on the digital stone translates into another language, which is randomly selected from 13 possibilities, including Arabic, Tamil, Sanskrit, Javanese, Hokkien, Hakka and Rohinya. To complicate matters, Tan also renders the translated text using a script that may not correspond (for example, a Hokkien translation in traditional Chinese script). The stone consequently has the potential to become incomprehensible to the viewer, unless they are a polyglot.

Tan’s approach alienates us from language and dispels the illusion that it is a transparent transmitter of meaning. His view of linguistic communication is anarchic. It is a shifting, ungovernable force that moves between different languages, scripts, races, nationalities and classes – existing ‘in motion and in multiplicity’, as he describes it in his essay ‘Accursed Tongues: Language in the Throes of Translation and Transliteration’, written for the catalogue that accompanies his most recent exhibition, The Tongue Has No Bones (2024), on view during July at A+ Works of Art, Kuala Lumpur.

While Tan’s practice examines the issues that arise when a singly unifying language governs a polyglot citizenry (ideas that will no doubt resonate with many), what hinders a more direct apprehension of his work is how local its references are: word games are played with languages used in Malaysia, which rely on a detailed understanding of the country’s cultural and political histories. I’m from nearby Singapore, a multilingual and multiracial society with a similar ethnic makeup, so the Malaysian languages are not far off from those used at home. The postcolonial histories of these two countries are also intertwined, Singapore having briefly been part of Malaysia before leaving in 1965 due to irreconcilable differences between the leaderships of each state. Despite this, I still needed to do some serious reading to unpack the meanings of the works I saw.

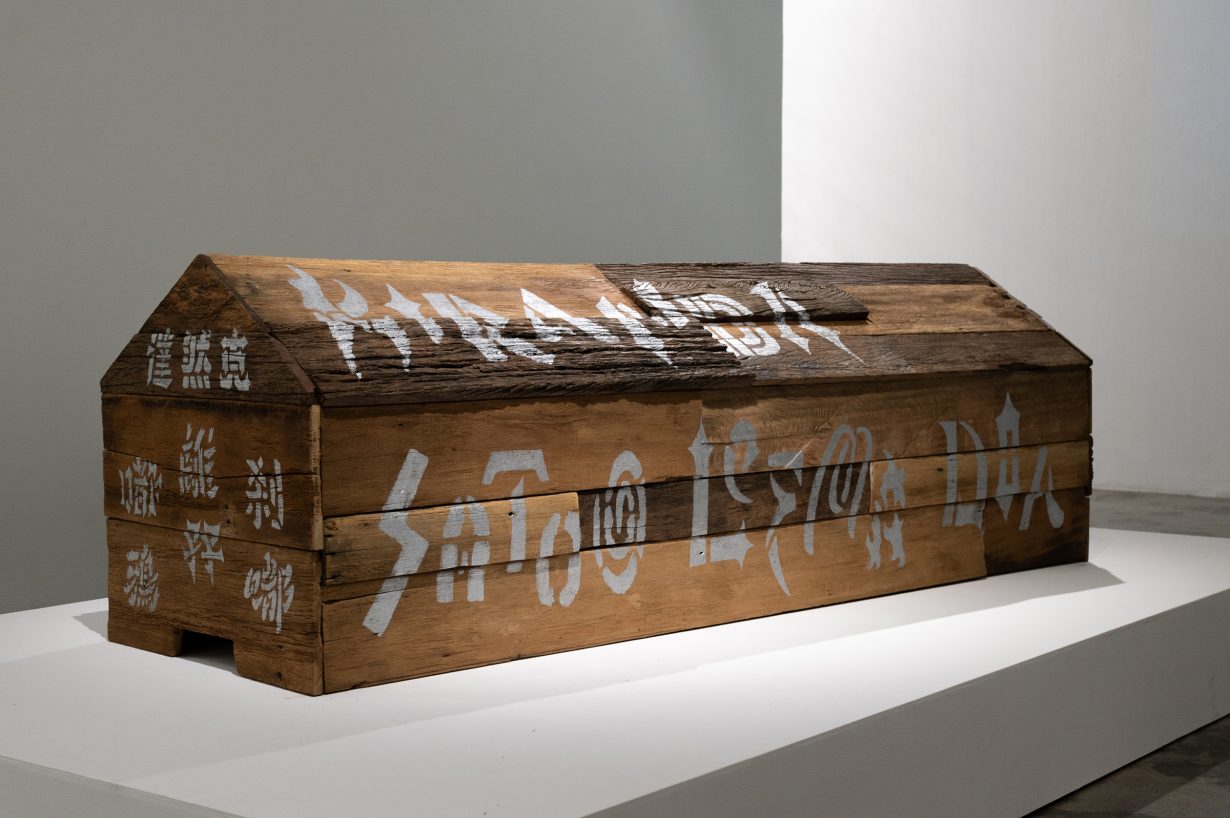

Take A Future Imperfect Presumed Dead (2024), an installation of a wooden coffin that has been printed with stencils of different languages, all phonetic transliterations of ‘keranda 152’. The work is inspired by the 1967 Keranda 152 protest (keranda means ‘coffin’ in Malay), when Malay language supremacists paraded the streets with a coffin to protest what they saw as the death of the National Language Act, which positioned Malay as the official state language. The protesters were aggrieved by the government’s extension of the use of English in legislative and judicial proceedings that year. The extension violated the promise made during independence from the British in 1957, in which English was allowed to be the official language for ten years to ensure a smooth transition; afterwards, Malay would be the sole official language. Tan’s work takes the coffin, a loaded symbol of linguistic protest and ethnonationalism in Malaysia, and inscribes diverse language scripts onto it – Chinese, Tamil and Jawi/Arabic – that spell out what is essentially a narrowly racialised political position.

In his catalogue essay, Tan broadens the understanding of translation so that it becomes a necessary condition of all linguistic communication. Writing down a language, for example, is in itself a translation. Tan writes: ‘The script is a language of a language. Not only does it transcribe and transliterate, but it also bleeds into and contorts pronunciation, thus initiating a subtle process of translation that escapes notice.’ I am in favour of the view that language is a constantly mutating agent. But in my encounter with Tan’s work, I found myself pondering another type of translation, which is the movement from intellectual concept to artwork. Could an idea be too perfectly realised, leaving little to no room for slippages and errant interpretations; for ‘idiosyncrasy and carelessness’, as Tan writes?

A recent work leaves greater room for ambiguity and feeling, using language not to convey meaning but rather to create atmosphere. In the video In The Beginning, R Was Only a Head (2024) we first encounter three people, one by one, from behind. The first is a man wearing a Malay baju (long-sleeved shirt) and songkok hat, the second a woman in an Indian saree and lastly a man in a Chinese mandarin jacket. As they each turn around, we see that they are racially ambiguous. Playing in the background is a male voice whispering over and over – “dressed him up like a Malay”, “dressed her up like an Indian”, “dressed him up like a Chinese” – creating an atmosphere of dread and foreboding. The phrase was inspired by a firsthand account of a Chinese man who survived the 13 May incident because a Malay family had ‘dressed him up like a Malay’.

The video was filmed at the photogenic Saloma Link Bridge in Kuala Lumpur, which has an LED facade that creates a pixelated version of the Malaysian flag at night. In the video we don’t see the flag – only gorgeous jewel tones in the background. In juxtaposition with the magical, almost romantic visuals, the rhythmic chanting in the background is malevolently insistent. “Dressed him up as a Malay dressed him up as a Malay dressed him up as a Malay.” Even as I walked away from the work, the video’s cadences continued to echo in my head. With its rich cinematography, the work is an uplifting story about interracial harmony and human decency. Yet there is something compulsive about the need to blend in for the purpose of survival, which suggests a nervousness not just around racial violence but more subtle forms of racial sublimation. In the end, the work paints a complex picture of Malaysian race relations that we experience more as ambience than argument.