Cold War: the mysterious at MAIIAM, Chiang Mai attempts to capture the felt plebeian texture of Thai political history

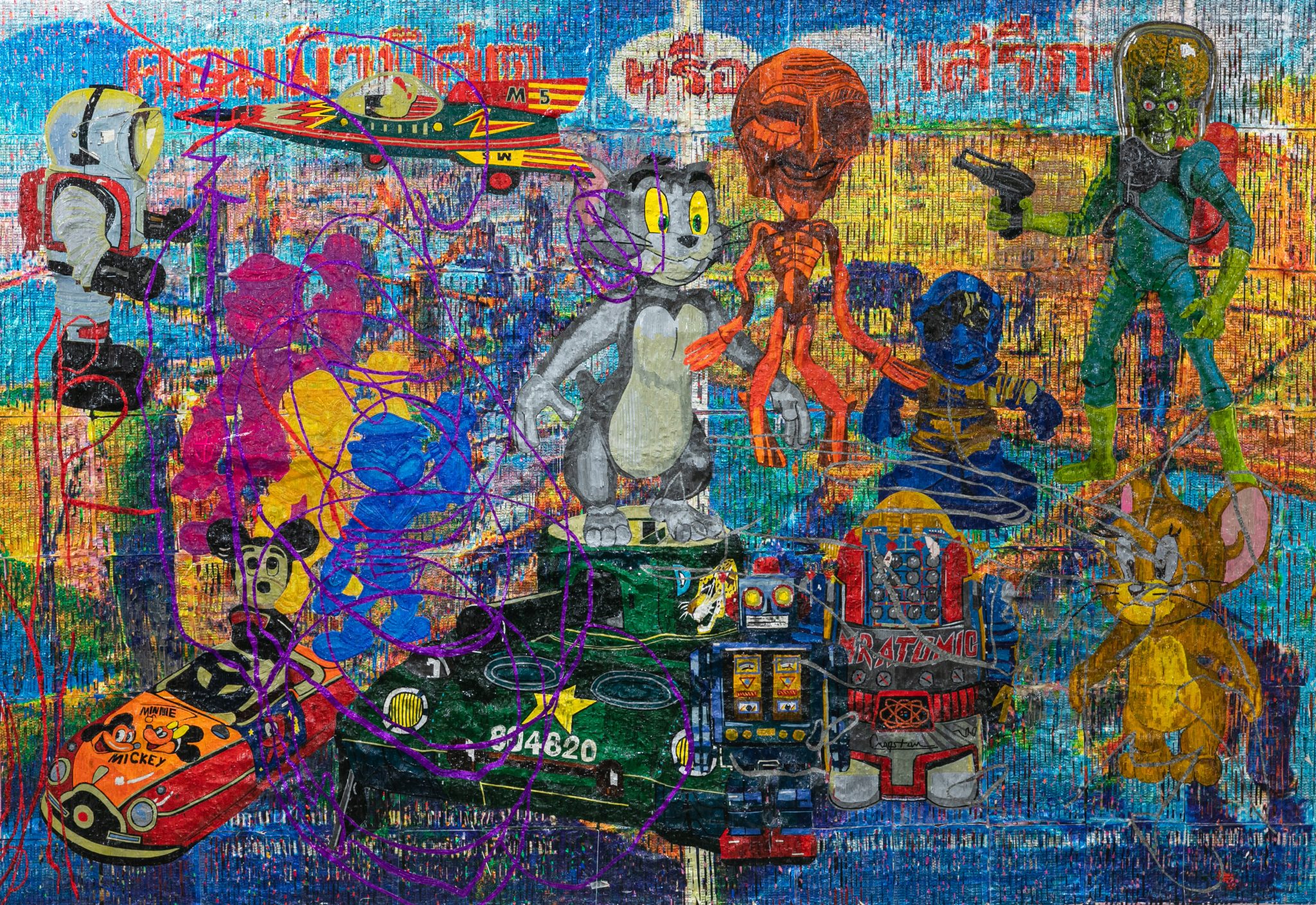

The dazzling giant in this display of over 60 collages by Chiang Mai-based artist and university lecturer Thasnai Sethaseree is not as spontaneous as it first appears. With each step closer, the billboard-size Cold War: the mysterious (2019–22) seems a little less indebted to the wild, improvisational gestures of action painting and a little more grounded in a particular time and place: the Cold War period in dictatorial Thailand. By the time you’ve reached the ‘do not cross’ line, layer upon layer of figurative elements – strips of shredded history books, comic book covers, the faces of political figures – can be seen floating amid a vast technicolour cosmos of blobs, orbs and scribbles.

A democracy activist and vocal firebrand in the Thai art scene, Sethaseree and his studio team layer thin strips of coloured paper over canvases thick with various materials, from Buddhist monk robes to digital prints, copper wire and dried rice paddy. This humble process is painstakingly deployed to achieve an ambitious end: capturing, through cacophonous blends of representational and non-representational elements, something of the felt plebeian texture of Thai political history. Within this context, Sethaseree’s biggest and most audacious show to date is a multi-chapter simulation of the obscurantism, violence and white noise of the Thai theatre-state since the Cold War – or more precisely, a multi-chapter simulation of the subjective, conscious experience of living under such alienating conditions.

Cast in this somewhat joyless light, Cold War: the mysterious, through its incessant spectacle and colossal scale reminiscent of neoclassical art, transports us into the chaos of the period rather than glorifying it. Many smaller works, meanwhile, meld nebulous Cold War imagery – from students and citizens killed in the 6 October 1976 massacre to children’s toys and newspaper headlines – with malignant colour splotches or swirling military camo patterns. In doing so, they reify the nature of official historiography, how the facts surrounding certain despotic episodes or traits have been distorted or hidden by pseudojournalists and state propaganda.

Short audio commentaries accessed via QR codes relate the episodes, from the 1976 return from exile of dictator Thanom Kittikachorn to the 2017 military checkpoint shooting of Lahu youth activist Chaiyaphum Pasae, around which works are arranged. This raises a danger of them being reduced to mere thematic signposts or placeholders, although one could argue that the situation in Thailand warrants didacticism. Many of the authoritarian tactics invoked here – the neutralisation of political opponents through both legal and extrajudicial means, the misleading of the public by an acquiescent media, the charges of communist or republican ambitions – are still in the counterinsurgent-right’s toolbox today.

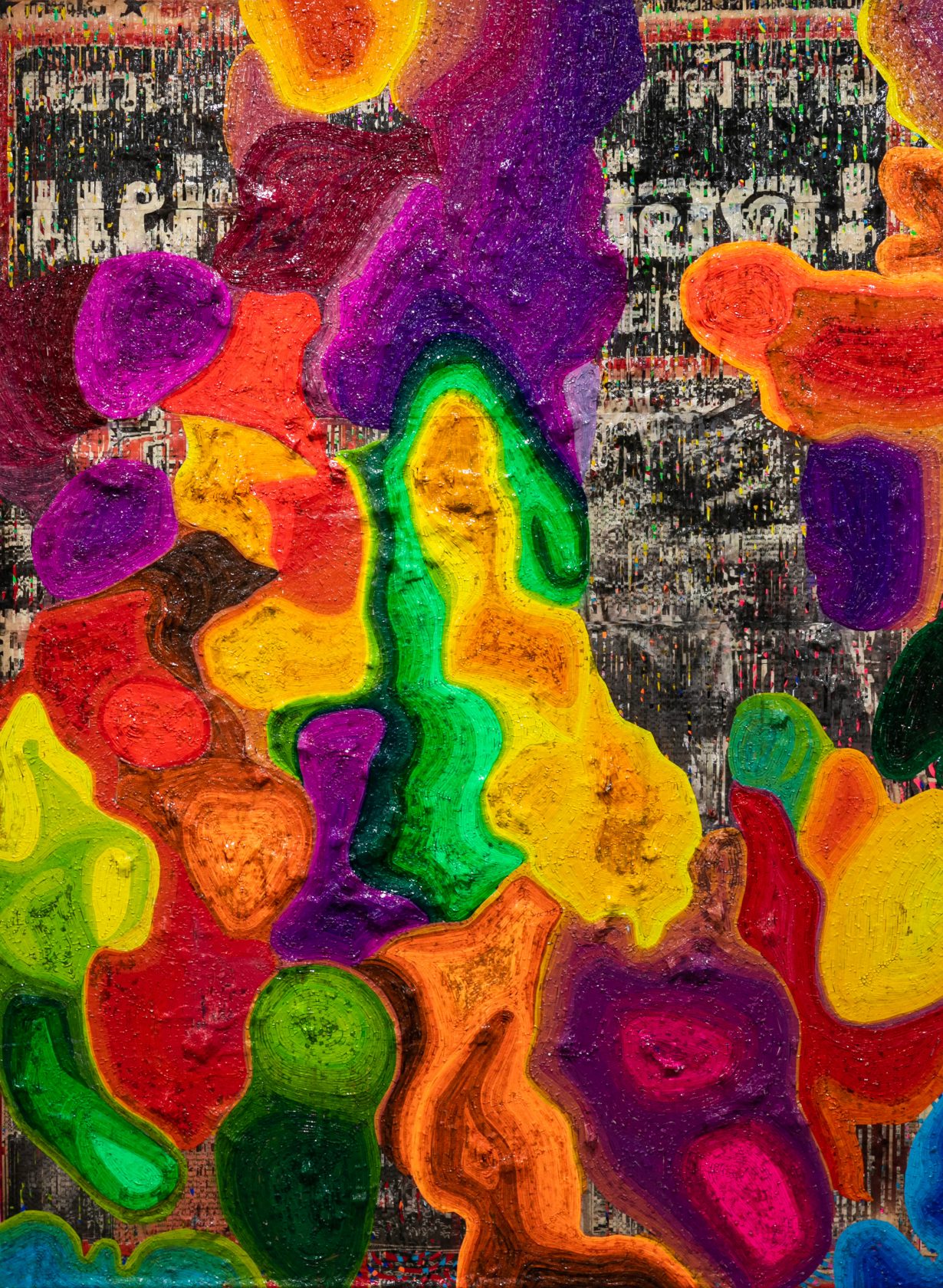

More importantly, the interaction of materiality and image gives these works a participatory quality that is itself a form of commentary. From a few metres back, Untitled (His code name is Pluto) (2021) consists of two cleverly halftoned images of Tiang Sirikhanth, a mid-twentieth-century democracy icon and founding member of the Free Thai Movement that agitated against Imperial Japan during the Second World War. On one side he is palpably alive; on the other, evidently dead, lying alongside four associates also brutally slain in 1949 by state officers. But up close we lose sight of this horrific incident: our attention shifts to the repeating spirals of coloured paper, reminiscent of ammonite fossils, stretching out friskily before us.

The critical payload of Sethaseree’s works depends upon this duality. Pricking our political consciousness from certain angles, dazzling us with their vitality from others, they invite unease about the spectacles that obscure certain truths, or versions of it, from view. And they also arguably indict the people as well as critique the Thai state – could it be that his effacement of trauma with doodles and razzle-dazzle echoes how blithely the Thai public switch off, unquestioningly and obediently compartmentalise or gloss over life’s crudely camouflaged injustices?

To parse these headstrong collages only in such moralistic terms, though, would be to deny both their craft origins and multidimensional energy. Drawing upon Northern Thailand’s traditional papercutting techniques, his excitable and often euphoric canvases and sculptures can also be read as playful ripostes to the state-sanctioned branding of the Lanna region – a former kingdom with Chiang Mai at its dynamic centre – as a land of decorous crafts, from sedate hanging paper lanterns to polite wood carvings. Impulsive and unstable, each effervescent surface refutes this tourist-friendly make-believe, screams out for us to hear, ‘In the North, our forms are as uncontainable and uncontrollable as we are’.

Cold War: the mysterious at MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum, Chiang Mai, through 14 February 2023