Our editors on the exhibitions they’re looking forward to this month, from Olivia Erlanger and Phuong Ngo to the expansion of São Paulo’s MASP

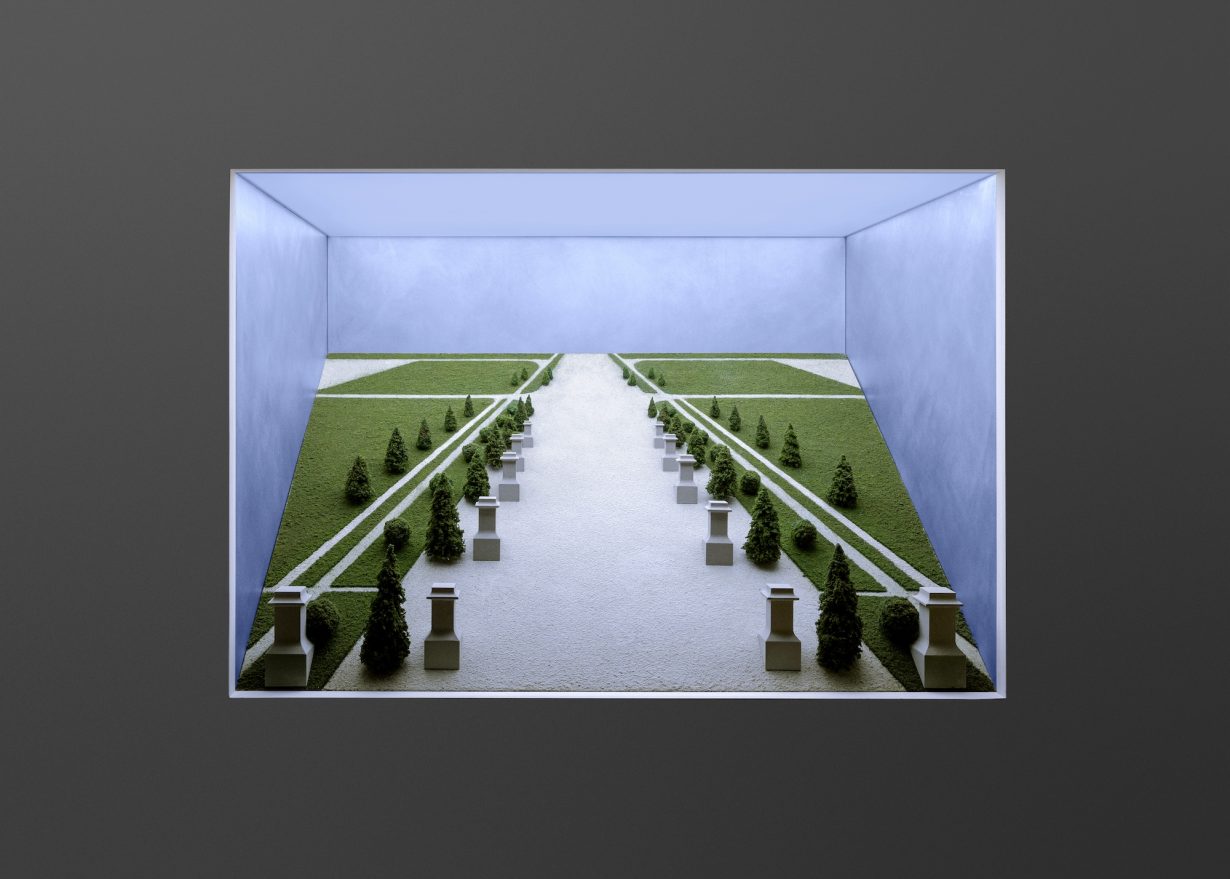

Olivia Erlanger: Spinoff

Luhring Augustine, New York, through 19 April

The New York-based artist Olivia Erlanger has spent a decade sifting through the spatial imaginary of America’s suburban middle class, scrutinising unsung architectural typologies such as garages – the subject of a research project she undertook with architect Luis Ortega Govela in the 2010s – and defamiliarising mundane commercial appliances. Erlanger went viral on Instagram in 2018 for her installation Ida, for which she placed silicone mermaid tails in the washers and driers of a laundromat in Los Angeles. Spinoff, a presentation of her new and recent works at Luhring Augustine’s Tribeca location, comes on the heels of her first solo exhibition at a US museum, If Today Were Tomorrow at Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, and features several of the works displayed there. Spinoff likewise traffics in figures of the uncanny, or unhomelike, shedding light on places and spaces frozen in stasis. A suite of graphite drawings depicts unfurnished domestic interiors juxtaposed with natural landscapes; in the centre of the space, three dioramas frame unpopulated vistas filled with miniature topiaries, rock formations and retro-futuristic buildings. There is no action here, much less violence: tension lies instead in the uncertainty of whether one has arrived before or after the cataclysm – or right in the eye of the storm. Jenny Wu

Phuong Ngo: Inheritance

West Space, Collingwood, Australia, 12 April – 7 June

If you happen to be part of a diaspora, or mixed-race, there’s a likelihood that at some point in your life you’re going to feel a little out of place. It might be when you notice that there are stark cultural differences in the communities you move between; it might be when someone feels the need to point out that you are not ‘enough’ of one culture or another; it might be when you find there’s a cultural disconnect between your experience of growing up in one place, while your parents grew up in another; or it might even be when you realise the kinds of sacrifices they made – the things, and the people, they left behind – to give you the life they dreamed of. It’s a kind of unintended inheritance, and one that serves as a starting point for Vietnamese-Australian multidisciplinary artist Phuong Ngo’s explorations into his own family history. As refugees of the Vietnam War, they became part of the mass exodus-by-sea of civilians known as the ‘Vietnamese boat people’ (1975–95). Across video, sculpture, photography, installation, photography, painting and performance, Ngo attempts to ‘reframe the histories of colonialism, conflict and displacement’, the introduction at West Space says. His latest project, Inheritance, takes place in three parts – each centring around ancestral materials as a means of acknowledging and negotiating suffering, grief, familial relationships and a wider diasporic history: ‘to re-image what was lost and to gift it to future generations.’ This first part of Inheritance will focus on the artist’s family dining table, typically a place of gathering and sharing but also, according to Ngo, ‘of punishment’, presenting ‘deconstructed re-imaginings of familial and ancestral objects’. Inheritance will incorporate materials from his ancestral home in Vietnam, video and a live performance on the opening night. Fi Churchman

Ali Cherri: How I Am Monument

Baltic Gateshead, 12 April – 12 October

How do we attribute value to artefacts? And why is one object collected and preserved in museums while another is excluded, destined to be either circulated endlessly on the open market or discarded altogether? The link between historical and cultural worth and the long hand of colonialism, nationalism and geopolitics is, one could say, about as clear as mud. It is a fitting idiom for the work of Lebanese artist Ali Cherri, for whom mud is the working material of choice. The anthropomorphic winged body of Cherri’s sculpture Sphinx (2024) and its vast plinth are fashioned from fragile dried mud, with its two amputated front limbs balanced precariously upon bronze prosthetic legs – an allegory for the many ways in which history is adapted, remixed and fabricated by those in power. What chance does a sculpture made of mud have of survival not only against the elements of wind and rain but even in the rarefied space of a museum? While in multichannel video installation Of Men and Gods and Mud (2022), for which Cherri was awarded the silver Lion at the 59th Venice Biennale, we follow a group of brickmakers as they rebuild their homes following their displacement for the construction of the Merowe Dam on the Nile River in Northern Sudan. It’s a stark reckoning with the disparity of economic means between local communities and state infrastructure. A new exhibition at Baltic continues a body of work first shown at Secession in Vienna (including Sphinx). The artist was unable to attend the opening last year; his parents had just been killed by Israeli bombs in Beirut. Cherri, who grew up in the Lebanese capital amid a civil war, doesn’t need anyone to tell him the stakes of political violence and the ways in which its impacts endure across generations, communities and the spaces they inhabit. He knows well the transience and tragedy of life, swept away like silt in a riverbed. Louise Benson

Museu de Arte de São Paulo: Expanding

Few art museums in the world have quite such a central role in local life as the Museu de Arte de São Paulo, and that is mostly a testament to its architecture and the institution’s original designer, Italian-born Brazilian modernist architect Lina Bo Bardi. Built in the middle of the Brazilian city’s Avenue Paulista in 1968, she elevated her glass block onto four red-painted concrete stilts, creating a natural meeting place beneath. The undercroft has long since been the place for political meetings, skateboarders, drifters, market sellers and more. Each election night, the press knows that this is the best place to set up their cameras, as it is here that the biggest victorious crowds will gather. The building will now be named after its architect, to distinguish it from its new partner, a converted neighbouring skyscraper, now appropriately named Edifício Pietro Maria, after Bo Bardi’s husband and one of the earliest directors of the institution. The 14-floor extension, with the two sites to be eventually connected by a tunnel, has just been inaugurated and, with a sense of Bo-Bardian harmony, comes in at 70 metres high with a length of 40 metres: the same dimensions as the original gallery. MASP was founded with a collection of European art, and appropriately enough a Renoir exhibition is the first to grace one of the ten floors to open to the public; with the art from Brazil’s other parent, Africa, filling another; a show titled Geometries on third; while Isaac Julien’s elegiac multiscreen video installation Lina Bo Bardi – A Marvelous Entanglement (2019), exploring the architect’s life, gets its Brazilian premier on another. Oliver Basciano

Nicolas Winding Refn & Hideo Kojima: Satellites

Prada Aoyama, Tokyo, 18 April – 25 August

What do you do when you’re in Director’s Jail? If you’re Danish director Nicolas Winding Refn, director of classics Pusher (1996) and Drive (2011), you open an exhibition with the Japanese game creator (and renowned celebrity selfie man – watch out Hans Ulrich) Hideo Kojima at Prada Aoyama Tokyo. The longtime friends have installed a movie set in the exhibition space: six television screens play images of Winding Refn and Kojima, in expansive conversation – in English and Japanese respectively – across the space, pondering various topics from the friendship they share, communication and dissolving digital identity, dreams and death. Each screen’s panelling is cut open, revealing the electrical components circuitry, as the machine is exposed and made vulnerable. In a nearby space, designed like a Hollywood dressing room, visitors can interact with a cassette player and stacks of tapes recorded by the artists: they range from conversational soundbites to cinema soundtracks, with AI-translated versions of Refn and Kojima’s conversation in various languages. Absurdity is a common trait of cinema and video games, constructed worlds that imitate our reality and also encourage its manipulation, distortion or subversion. The set’s imaginary world, the avatar in a void, the spoken word across languages – here, all forms sitting on the precipice of union and alienation. Alexander Leissle

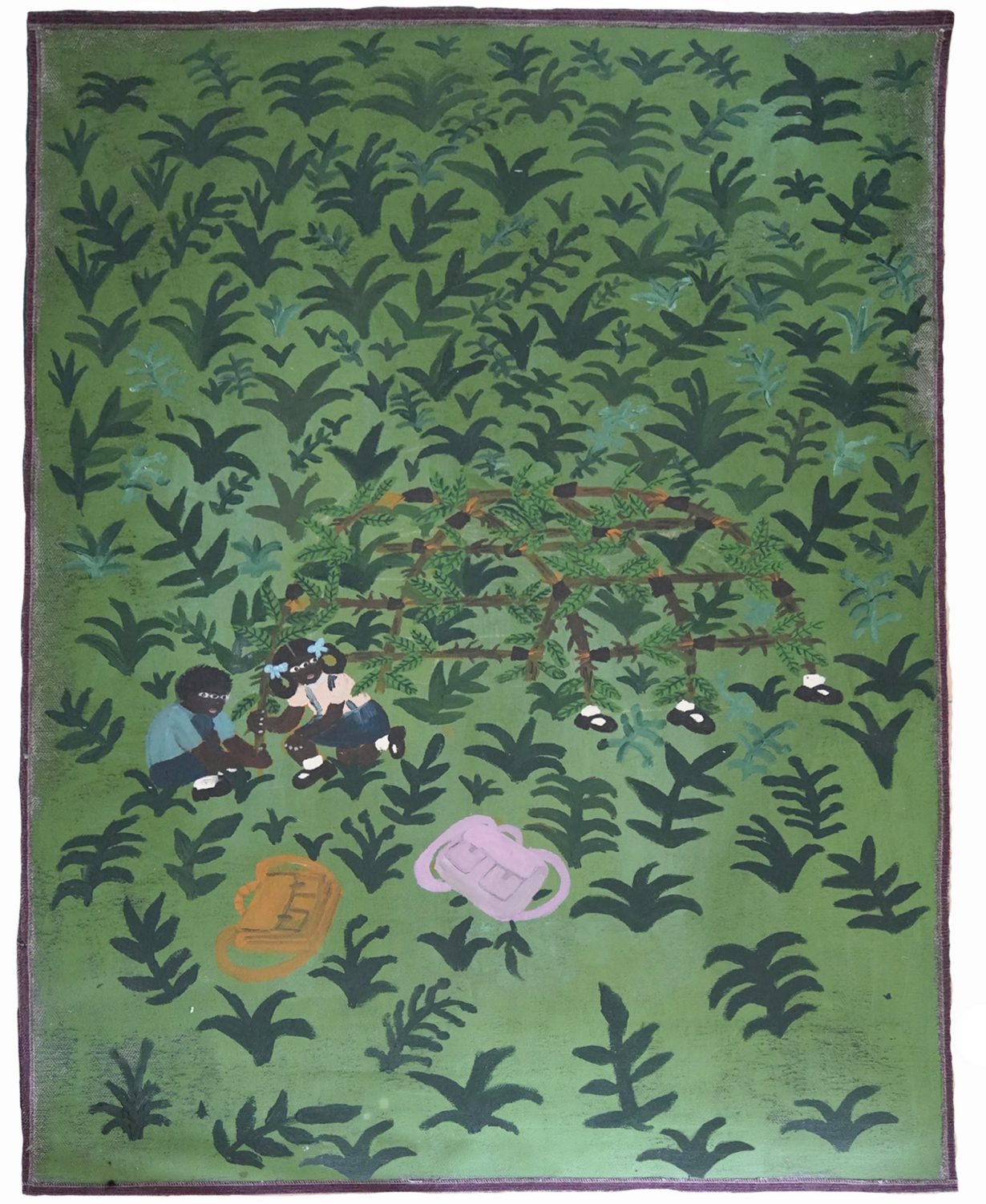

The Plantation Plot

ILHAM Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, 20 April – 21 September

Did you know that most coconuts in Southeast Asian coconut farms are picked by indentured monkeys? A male monkey can pick an average of 1,600 coconuts a day, twenty times the 80 which humans are capable of. The monkeys’ contribution to our capitalist economy has much to reveal about how we’ve come to see land and nature as a kind of factory and production line, with an obsession for productivity and growth and without care for repercussions, part of the legacy of the plantation economy. The Plantation Plot at ILHAM Gallery examines the history of these cash-crop farms and their persistence into today’s world. Amongst the 27 artists gathered by curator Sheau Yun Lim, some focus on the environmental and human costs of colonial agriculture. Uitoto artist Santiago Yahuarcani’s painting series Castigos del caucho (2017) examines the horrific destruction rubber plantations brought to the Amazon forest and its Indigenous communities – who were enslaved to tap rubber trees, then slaughtered in a series of genocides – during ‘the rubber boom’ between the 1870s and 1910s. While Indo-Caribbean artist Kelly Sinnapah Mary’s series of sculptures and paintings, Notebook 10 (2020–21), imagines the surreal world of the artist’s indentured ancestors who were brought from India to Guadeloupe, mingling Hindu gods and flora and fauna of the Americas. Others find plantations tethered to everyday items. Corey McCorkle’s 2016 installation Pendulum hangs bunches of ‘Cavendish bananas’ – the kind found in European supermarkets – midair, tracing the fruit’s movement from Mauritius to nineteenth century England, before being introduced to colonised Samoa to launch its own banana business. Taken together, The Plantation Plot is a winding story that traces how plantations shape the world through pains and gains, and how we as consumers within this economy are implicated in this open-door factory (and slaughterhouse) this legacy has created. Yuwen Jiang

Syd Mead: Future Pastime

534 W 26th St, New York, through 21 May

Retrofuturism – that enduring culture fascinated with the way the future was imagined by the past – would be poorer without American designer Syd Mead, who created the concept designs for films such as Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982). Because while much future-nostalgia now dwells somewhere between steampunk and cyberpunk (both inventions of the 1980s and 1990s), Mead managed, from the 1970s through to the twenty-first century, to conjure an image of a human future not defined solely by dystopia. Mead’s future is expansive, both rational and playful, a world of high-tech and a megastructure-sized urban world harnessed to the service of human needs and, more often than not, to human leisure and play. Mead’s training in industrial design, his work as a concept designer for Ford in the 1960s, grounded him in how to make the future materially and technically believable, but his technique – usually gouache on panel – allowed him to set his machinery in a more classical and romantic tradition of landscape painting, and by the 1970s, Mead had turned fully towards sci-fi, while continuing to work with high-end industrial design. But it was his reimagining of a potentially limitless future, on- and off-world, that continued the optimism of the earlier 20th century. Future Pastime, a pop-up put together by fans Elon Solo and William Corman, highlights the hedonism, bringing together sixteen of Mead’s large panel gouaches from three decades of his output. It’s a mix of amped up sporting spectacles, from racing robotic dogs to space yachts, and partying, which suggest something of Mead’s desire for a future that was as individually and culturally liberated as it was technologically unbounded. Where might they be partying? Maybe on Moon 2000 (1979) a view of earth’s satellite, seen through blue atmospheric haze of an Earth morning. But it’s a moon belted by a huge band of human construction. At a moment when tech oligarchs are in a race to colonise Mars, Mead’s visionary maximalism is a reminder that the future is a place defined by the politics of the present, now perhaps more than ever. J.J. Charlesworth

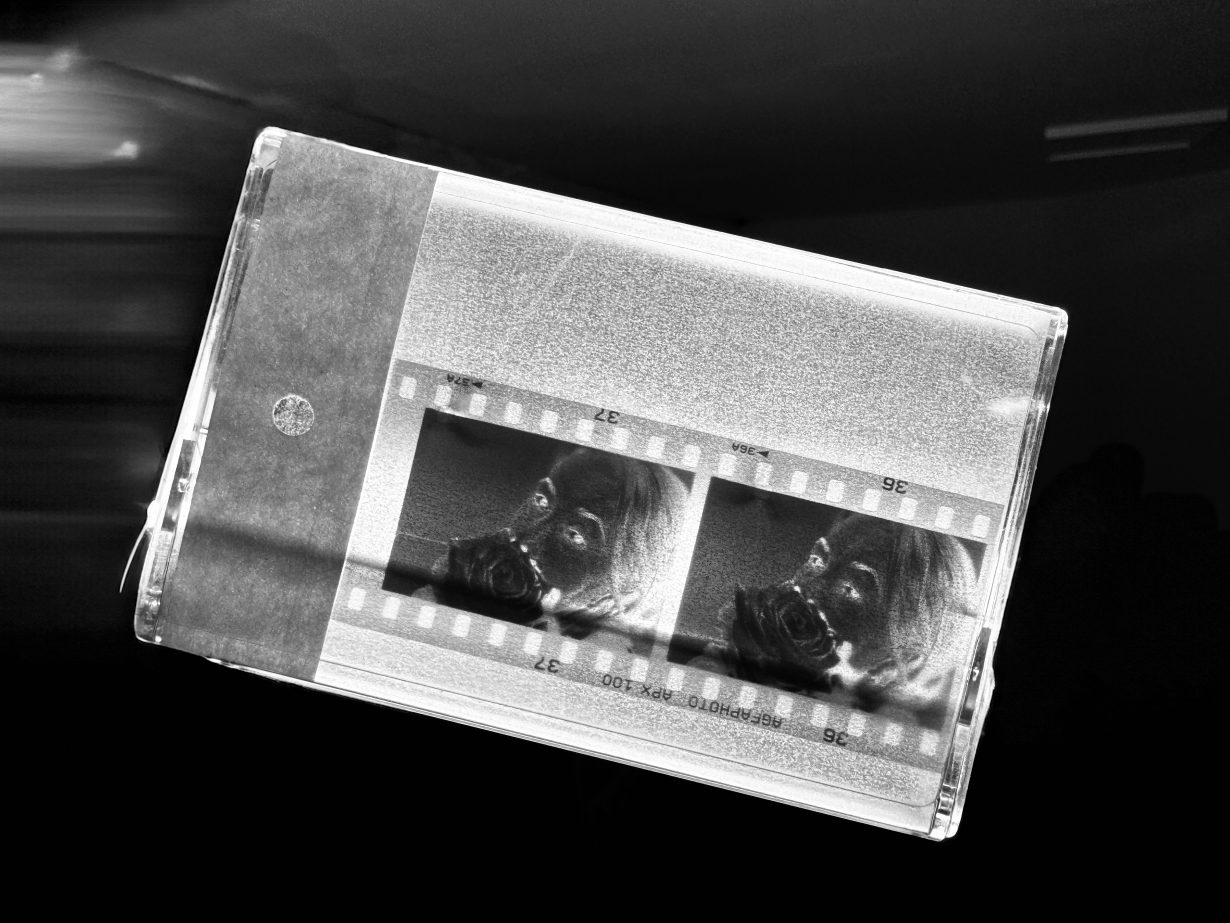

Keta Gavasheli: Skład pamięci

Wschód, New York, 5 April – 17 May

At Wschód, New York, Keta Gavasheli will present inkjet-printed panoramic images on canvas, alongside three-dimensional and video work, in response to the art-historical legacy of Polish painter and theatre director Tadeusz Kantor (1915–1990). At the centre of Gavasheli’s first US solo exhibition, Skład pamięci, or Memory entrepôt, will be a ‘Happening’ that Kantor organised in Warsaw in 1967, titled The Letter, the seed for which was planted when the late artist visited New York and encountered the storage rooms of the US Postal Service. The Letter consisted of a group of postmen carrying an absurdly sized letter – 14 metres long and 2 metres tall – from a post office on Ordynacka Street to Foksal Gallery, where it was collectively and aggressively destroyed (photographs from the event are all bodies and blurs). According to an account by curator Pawel Polit, updates on the letter’s whereabouts as it travelled to the gallery were broadcast ‘in order to increase the emotional temperature of the public’. In Skład pamięci, recorded sounds from Kantor’s Happening will also permeate the gallery, evoking the warmth and friction of intergenerational dialogue. Gavasheli, who was born in Tbilisi the year Kantor died, is best known for works that reference holes – particularly plugholes and manholes. Writing in 2021 for WORMHOLE Newspaper, she described what was ‘infinite and strangely appealing about’ her bathroom drain: the fact that a humble orifice could insinuate a vast and complex system connecting the diurnal rhythms of innumerable strangers. Likewise, Skład pamięci might be thought of as a portal the artist has opened onto a long and labyrinthine history of artistic provocation. Jenny Wu

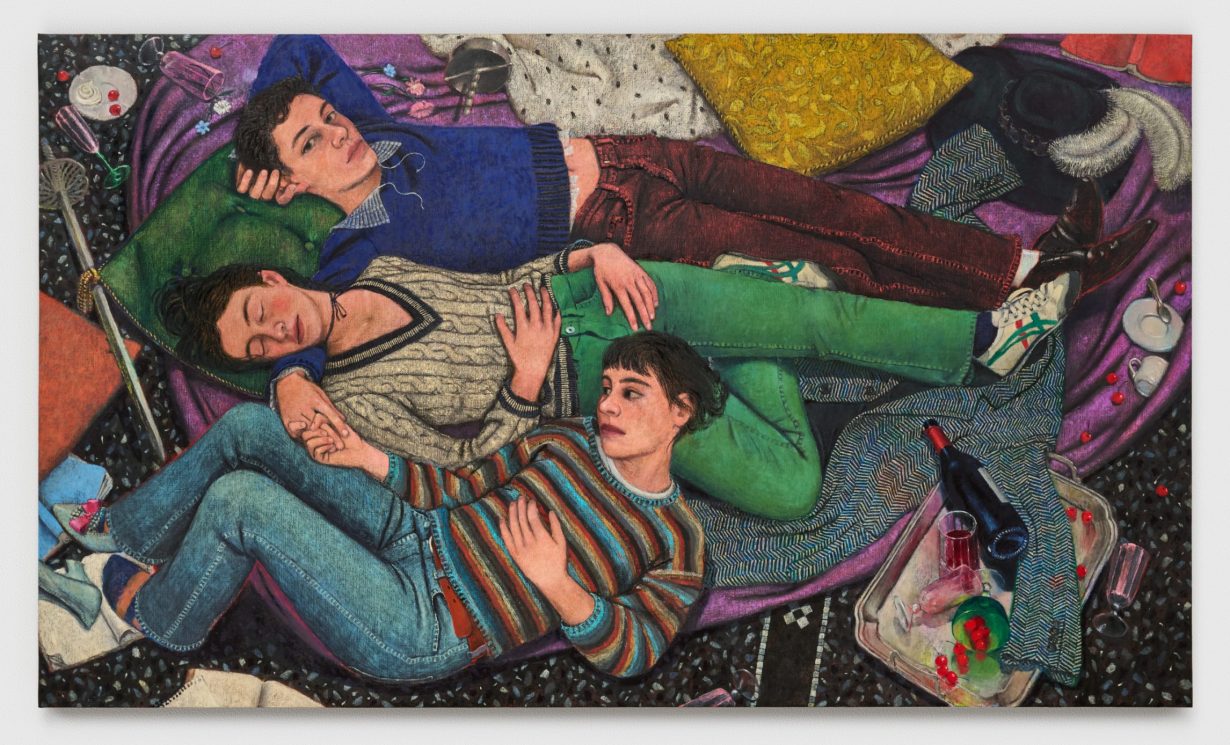

Emilio Gola: Sans Souci

Galeria Madragoa, Lisbon, through 17 May

The insouciant young subjects of Emilio Gola’s paintings lie in repose among scattered books, dinner plates, wine bottles and fruit, as if they had just landed among a decadent seventeenth-century Dutch still-life painting. Each object appears carefully placed just-so, replete with symbolism yet stubbornly ordinary. A palm frond here, a few cherries there. Each of Gola’s scenes is a paean to the everyday pleasures of conviviality and al-fresco lounging, as much a nod to Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863) as to Nan Goldin’s Picnic on the Esplanade (1953). These are moments of escape from the pressures of society, hinted at just beyond the tightly cropped frame, however momentary that reprieve may be. Born and based in Milan, Gola has a background in architectural design, which may inform the careful attention paid to the materiality of everything from the tiled flooring peeking out from beneath a picnic blanket to the clashing patterns on overlapping textiles in a herringbone wool weave. At Galeria Madragoa in Lisbon, a stone’s throw from the tranquil Jardim da Estrela, it is as if a dreamy vision of the garden’s grassy lawns has landed indoors, inviting passers-by outside the tall gallery windows to stop and take pause. Gola has named the show sans souci: without worry. Yet a hum of disquiet manages to creep in as the viewer meets the direct gaze of his protagonists, each looking outwards with a sly glance to what lies beyond their immediate surroundings. It is notable that the exhibition’s title is defined, after all, by what it is not. Louise Benson

Repast: The Story of Food by Jenny Linford. Thames & Hudson, 24 April

Spanning from 7000 year old rock carvings of longhorn cattle in Algeria to a lead cod-shaped fish hook made in Newfoundland in 2000, this visually-led survey takes a look at ‘how humans have fed themselves through the ages’, through objects used for and depictions of hunting, farming, cooking and, yes, eating. Taking its cue from the British Museum’s radio show, book and touring exhibition History of the World in 100 Objects (2010), Jenny Linford – a longtime food writer, podcaster and the author of several cookbooks and the treatise on time in food, The Missing Ingredient – delves into the collection of the Museum to showcase much more than just 100 treasures. There’s an 87cm-long ancient Sumerian beer drinking straw, made with gold, silver and lapis lazuli; and a late Qing dynasty Ivory chopstick case that also held a knife, a pick, and some ear cleaners. It’s a global tour, reflective of the Museum’s history in that it features strongly on British, Chinese, Indian, Japanese, Ghanaian and Greek artefacts, with more occasional forays into other cultures. But Linford’s selection shows us how times, and tastes, have changed: one small blue sugar bowl from the 1820s, made as part of an abolitionist tea set, that proclaims in gold lettering, ‘East India Sugar: not made by SLAVES’, is evidently not quite the own it was intended to be. Chris Fite-Wassilak