Our editors on the exhibitions they’re looking forward to this month, from Jeddah’s Islamic Arts Biennale 2025 to an exhibition of Brazilian modernism

Islamic Arts Biennale 2025: And all that is in between

Western Hajj Terminal, King Abdulaziz International Airport, Jeddah, 25 January–25 May

Jeddah’s Islamic Arts Biennale returns for its second edition this month with 31 international participating artists and artist groups (whose works will be shown alongside a showcase of historical objects and artefacts) organised under the title And All That Is In Between. The theme reflects on ‘how faith is lived, expressed, and celebrated.’ Which means that the biennale hinges not on whether you believe in one god or multiple gods, or no gods – but rather the act of keeping faith and how that faith is expressed via creative acts. That might look like the work of the Riyadh-based photographer and artist Hayat Osamah, whose work with publications including Vogue, Marie Claire and Harpers Bazaar reflects a devotion not only to fashion, but also to the way in which contemporary Middle Eastern culture and identity is portrayed in this context – in 2023, the artist presented the sculpture Dust to Dust at the light art festival Noor Riyadh, which was composed of compostable textiles ‘dyed to mimic different skin tones’, and whose shape was inspired by sand dunes. Meanwhile, Asim Waqif’s practice incorporates architecture, art and design to engage with issues around ecological management, waste and water, as well as the politics of occupying public spaces (his most recent solo exhibition at Pittsburgh’s Mattress Factory in 2023, titled Assume the Risk, invited visitors to participate in the exhibition by recomposing the wooden installation). Also presented will be works by Charwei Tsai, best known for her multidisciplinary practice that often incorporates the performing of rituals and the inscription of the Buddhist Heart Sutra on various organic materials including flowers, mushrooms, tofu, shells, leaves and baby octopuses. Faith, it turns out, can be found in everything and nothing. Fi Churchman

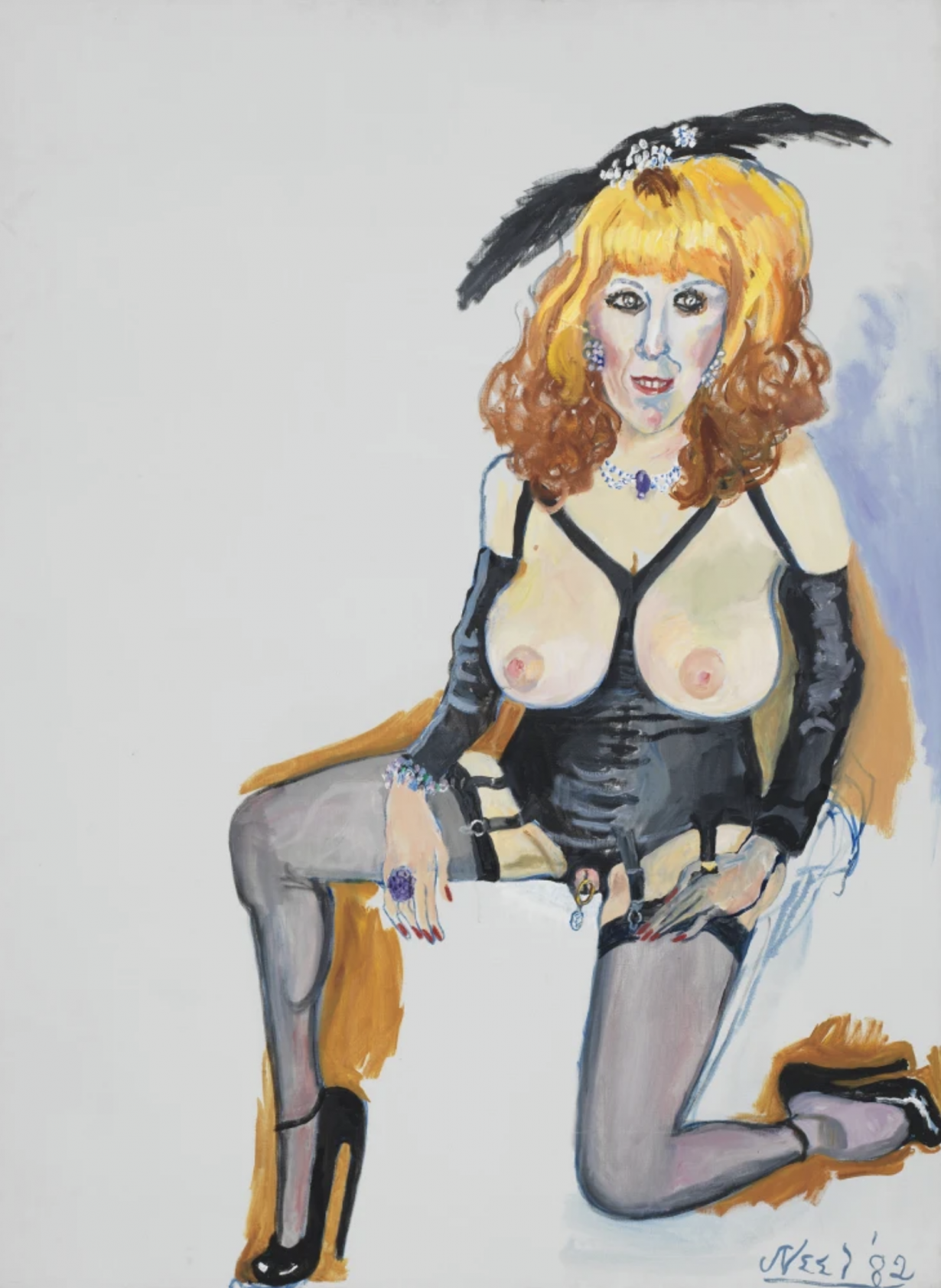

Alice Neel in the Queer World

Victoria Miro, London, 30 January–8 March

To sit down and read a book is most often an act undertaken alone. Yet the decision to read aloud to another person, whether a child, a friend, a stranger or a lover, has the powerful effect of opening up this otherwise solitary pursuit in a manner that can feel surprisingly intimate. This is the closest comparison I can find to the act of painting a portrait from life, whereby the artist and sitter come together in shared physical proximity even as their minds diverge and intersect within their own private, imaginary worlds: at once near and far. For Alice Neel, her practice of painting people from many walks of life, from neighbours to writers, performers, artists, politicians and activists – friends and strangers – led her to share this intimate space with a dizzyingly diverse range of subjects. This exhibition, curated by writer Hilton Als (the latest iteration of one first staged at David Zwirner Los Angeles at the end of 2024) focuses on Neel’s portraits of figures from the queer scene in New York over a period of more than 30 years, from the 1950s to early 1980s. There is an unnamed ballet dancer, painted in 1950 in a black leotard with one leg drawn languorously up to his chest. Or artist and performer Annie Sprinkle, who showed off her labia piercing in fetish garb during multiple sittings of over four hours. ‘The year 1982 was the era of anti-porn feminism, but she just saw the joy and the fun,’ Sprinkle later recalled. ‘I would say it was an erotic experience,’ she added. ‘Alice and I were making love through art.’ As Als writes in the accompanying catalogue: ‘[Neel] seemed to be saying in canvas after canvas that there was no word or image that could equal those fleeting moments of joy – of connectedness – that bound her not only to her subjects, but to painting itself, that solitary act that she performed in front of other people. Louise Benson

After the End: Cartographies for Another Time

Centre Pompidou-Metz, France, 25 January–1 September

‘Modernity and colonialism have gone hand in hand since their inception’, Manuel Borja-Villel wrote in ArtReview April 2024, as he questioned the possibility of decolonising the artworld. ‘Modernity imposed two temporalities: one of the colonisers and another of the colonised. The former placed themselves at the centre, in the present, the latter were relegated to the periphery, permanently located in the past.’ After the End. Cartographies for Another Time at Centre Pompidou-Metz, curated by Borja-Villel, takes this key principle of phenomenological temporality – our experience of time, or time-ness – and explores its relationship to imperial modernity. Taking its lead from Caribbean and North African diasporas, After the End asks what a world built on their ideals – common and unique – might look like. One such artist is Abdessamad El Montassir, whose multichannel video and soundwork Al Amakine (The locations, 2016-20), undertakes a kind of multimedia cartography of the South-Moroccan Sahara. In abstract videos, landscape photographs, plant lightboxes and spoken narration played throughout the gallery, El Montassir pursues a kind of re-historisization, wilfully dislocating hitherto received understanding of the land’s endogenous history. Which means fictional storytelling, a plurality of human and botanical narrators, photography, science and fiction presented as of equal veracity. We cannot, at least in any epistemological sense, understand the future; but there must be other ways of synthesising the present. Alexander Leissle

TAF Symposium: Soul Song of a New Organisation

Tanoto Art Foundation, Singapore, 14 January

Singapore Art Week Forum

National Gallery Singapore, 15 January

The freshly minted, Singapore-based Tanoto Art Foundation launches with a one-day symposium taking place in the lead-up to this year’s Singapore Art Week. Established and led by trustee Belinda Tanoto, the foundation will look to explore the networks and solidarities within the wildly diverse Southeast Asian art scene. Its opening act is the symposium, titled ‘Soul Song of a New Organisation’ – suggesting the organisation is some sort of organism – with a keynote lecture by art-historian Joan Kee, performances by Melati Suryodarmo and Chang Yuchen, and further contributions by curator Joselina Cruz and artist Gala Porras-Kim, among others. According to the foundation’s artistic director, Weng Xiaoyu, the point of the whole thing is ‘to nurture TAF’s soul by expanding our imagination on how to create an organisation, from challenges to out-of-the-box ideas, and new ways of collaborations’, which is elliptical, at best, but will hopefully lead to something that can have a clearer, positive impact on Singapore’s art ecology. Particularly given that Tanoto’s paper businesses have, in the past, been controversial in terms of their engagement with the natural ecologies of Southeast Asia. Back in the art ecology, if symposia are your bag then you’re in luck: Singapore’s art scene is going symposia crazy. The Singapore Art Week Forum takes place the day after the Tanoto jamboree, and features Chicago-base roofing-fetishist, community mobiliser and urban-upgrader Theaster Gates, Vietnamese visual arts–life sciences crossover collective Art Labor and Sri Lanka’s Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art founder Sharmini Pereira, among others, on the bill. For those of you that worry that the artworld is all talk and no trousers, you can hitch up your britches and waddle off to ArtSG, the island paradise’s casino-based art fair, which opens its doors to the public the day after the talking stops. Nirmala Devi

Dawoud Bey: Stony the Road

Sean Kelly, New York, 10 January–22 February

In the five decades since he first encountered the work of Harlem Renaissance photographer James Van Der Zee during an impromptu visit to the Met, lens-based artist Dawoud Bey has produced tender, complex portraits of Black subjects in the United States, as well as studies of forests, farmhouses and bodies of water in sites significant to African American history. At Sean Kelly, Bey will present Stony the Road, an exhibition of large-format gelatin silver prints and a black-and-white film. These works, previously shown at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, depict a wooded trail that runs along the James River in Richmond, Virginia, a city that served as a trafficking hub during the Transatlantic slave trade and the capital of the secessionist Confederacy during the American Civil War (1861–1865). Bey’s landscape photographs – darkly printed, lyrical and lonely – are neither works of photojournalism nor restagings of violent episodes in US history. Their power derives from Bey’s choice to withhold mention of the human subject – his refusal, in a sense, to walk the fine line between witness and spectacle. At a time when American lawmakers are attempting to censor discussions of racism and slavery in schools and our screens are saturated with images of explicit brutality, Bey’s lush and haunted landscapes come as panaceas for the mind’s eye and, importantly, model alternative ways to visualise history’s wounds. Jenny Wu

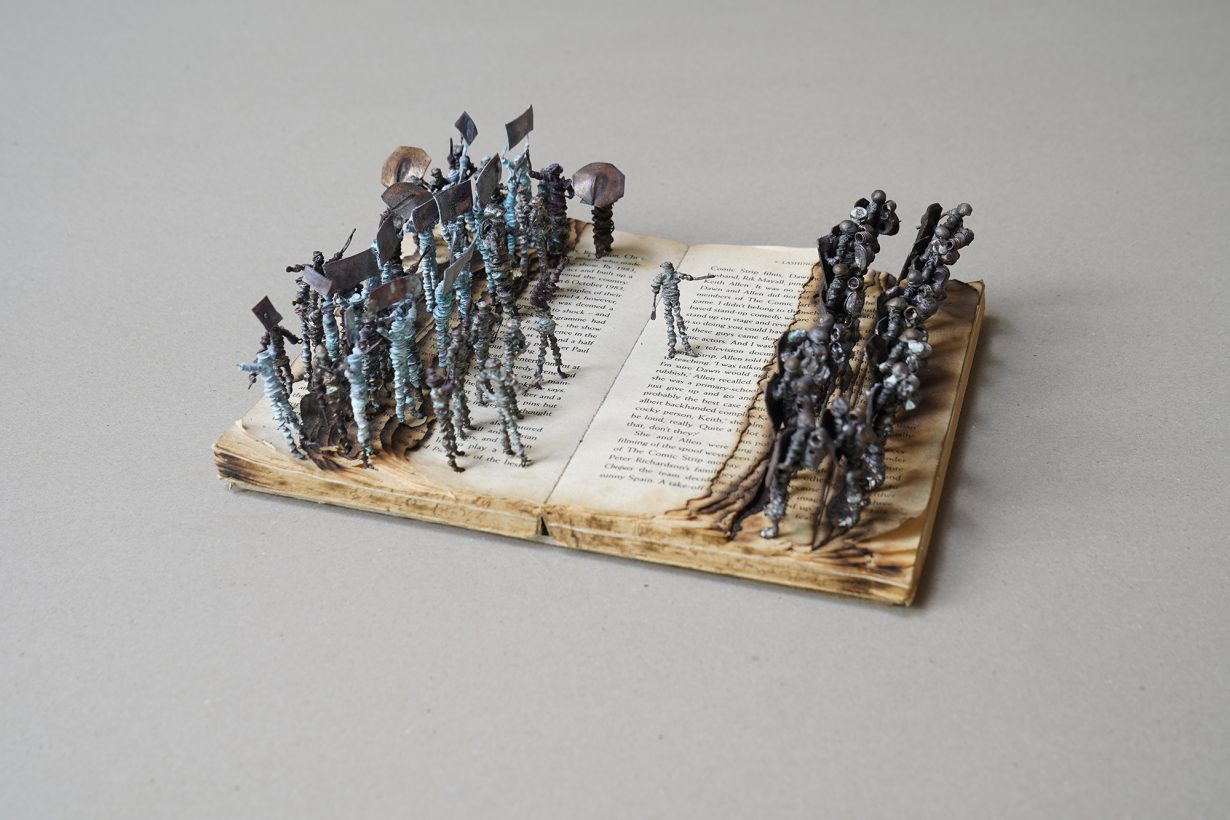

Kingsley Gunatillake: Maara

Saskia Fernando Gallery, Colombo, 23 January–13 February

For over 30 years, Sri Lankan artist Kingsley Gunatillake has worked across painting, drawing and sculpture, relying on multiple artistic traditions. He is especially known for making paintings that are predominantly abstract, full of robust gesture and monumental forms, as well as for his ‘book art’ sculptures. For these, the artist works into found books, cutting out spaces within the layered pages and inserting into them other found objects, or otherwise binding or encasing the pages, making works that speak to the long history of ethnic conflict and civil war Sri Lanka suffered from 1983 to 2009. These book works allude to the human and political costs of the war and its aftermath, subjecting the embodied knowledge and culture represented by the printed book to all kinds of violence: charring the pages, locking them shut in iron cages or clusters of padlocks, or else embedding spent bullet cases or armies of miniature soldiers. Sri Lanka’s precarious democracy is a contrasting theme – explored within groups of tiny placard-waving protestors, or else in the ‘X’ marks of voters that burn through the pages of a work such as Election (2019). This solo show, presenting new paintings and sculptures, will be the artist’s first at Saskia Fernando Gallery since 2020. J.J. Charlesworth

Citra Sasmita: Into Eternal Land

Barbican Centre, London, 30 January–21 April

It’s going to be the Year of the Snake starting 29 January. Appropriate then, that from the second day of the new lunar year, the Barbican Centre will be showing the first UK solo of Indonesian artist Citra Sasmita, whose fabric paintings often include serpent-shaped goddesses and Nagas – and anything mishmashed between a woman and one of these limbless reptiles. Born in Bali, Sasmita studied literature and physics, before teaching herself painting in the Kamasan tradition, which originated in the eponymous Balinese village around the fifteenth century and was largely reserved for male artists. Appropriating the classical style – heavily patterned, with chromatic beige hues interspersed with sepia-tinged colours – Sasmitra’s compositions would diverge from its typical depictions of scenes from Hindu epics, picturing instead historical heroines and colonial atrocities, inserting women back into the mythical-political narrative that largely defined the way the multiethnic country imagined its national identity. At The Curve, there will be a panoramic scroll painting Into Eternal Land, newly commissioned for the gallery’s elongated space. Unfolding like a classical epic are histories of migration across the Indonesian archipelago, as well as stories of passing between the heavenly and the underworld. Yuwen Jiang

Brasil! Brasil! The Birth of Modernism

Royal Academy, London, 28 January–21 April

Djanira da Motta e Silva was newly married when she was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Moved to a sanatorium in São Jose dos Campos, a city in the Brazilian state of São Paulo, she whiled away the days of her recovering by drawing and painting ‘the modest world around me: my animals, my balcony, the interior of the house, portraits of neighbours. A loving study of observation of the things I cherished.’ Mixed-race Indigenous, her husband in the merchant navy, Djanira’s life behind the hospital gates was far removed from the avant-garde milieu of 1930s São Paulo or Rio de Janeiro, but in the Royal Academy’s historic survey of the country it is clear how she began to plug her work into the latest trends – Expressionism, Futurism and Cubism – while retaining a Brazilian folk vernacular. The groundwork for this project of making a Brazilian modernism, and indeed the project of making a modern Brazil, had been laid by figures from the privileged classes (the likes of Tarsila de Amaral and Oswald de Andrade, who also feature alongside artists such as Volpi, Vicente do Rego Monteiro, Ruben Valentin and Candido Portinari) but Djanira’s career is the epitome of the utopian ideals that underpinned the pursuit. A decade later she entered the Carioca artistic classes, sponsored by Lasar Segall, and by the 1960s she was fully established. Oliver Basciano

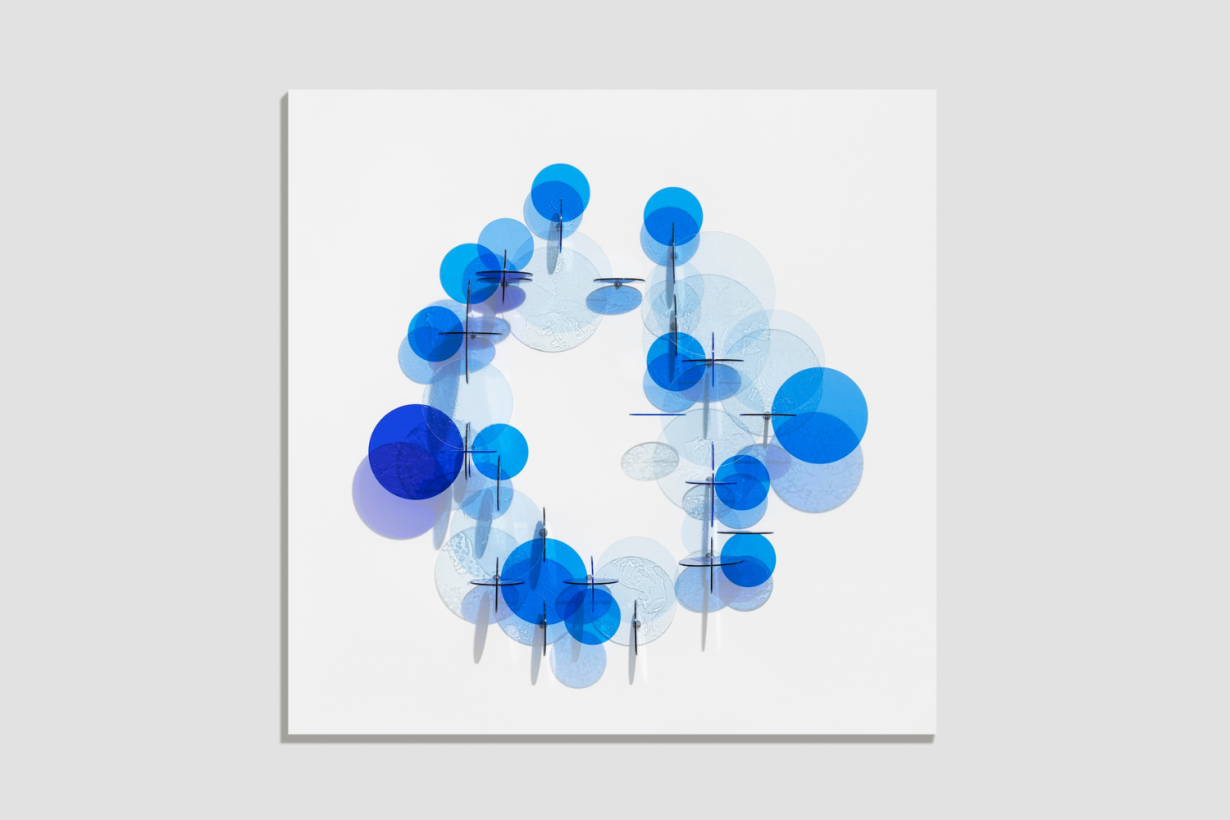

Suzann Victor: Constellations

STPI, Singapore, 15 January–2 March

Australia-based Singaporean Suzann Victor has been a driving force in Singapore’s art scene for several decades now. During the early 1990s she cofounded and directed the influential artist-run space 5th Passage (the city-state has precious few such entities today) and was one of the artists selected to represent Singapore for its inaugural participation at the Venice Biennale in 2001. Her exhibition at STPI, the product of her second residency at the print workshop, features a typically innovative use of translucent acrylic disks to create ‘prints’ of light and shade on the gallery walls, that in turn takes inspiration from natural networks – roots, electricity, etc – that normally remain unseen by human eyes. There’s a clear message in all this – about looking at that which we normally overlook (on the subject of which it would be another two decades after Victor’s exhibition before Singapore was represented at the Venice Biennale by a second female artist). Nirmala Devi

Łukasz Twarkowski: The Employees

Southbank Centre’s Queen Elizabeth Hall, 16–19 January

Genre-splicing Polish dramaturge Łukasz Twarkowski has made his name with productions that bleed theatre design into art installation and multimedia environment, and theatre into performance art, while his ‘plays’ turn on dystopian and utopian reflections on control and human agency, not least in the way Twarkowski disorders the place of the audience within his works, and how their often fragmented, non-linear narrative forms are populated by characters whose sense self is fluid and changing. So Olga Ravn’s 2020 science-fiction novel The Employees might be an ideal story for Twarkorwski’s treatment; Ravn’s novel is staged as a series of staccato HR-type interviews with the human and humanoid crew of an interstellar spacecraft, who are also caring for a series of ‘alien’ artefacts. It’s never clear if the purpose of these reports relates to employee wellbeing, improving workplace efficiency or simply to the accumulation of data for some obscure social experiment, but as the plot revolves around the relations between human and non-human staff, what might still be understood as human is up for grabs. Premiered in Warsaw in 2023, Twarkowski’s adaptation sets the employees in a claustrophobic, mazelike structure of steel and perspex, their audiences witness to how their professional discipline is unravelled by the realisation that they may be all that is left of being human. J.J. Charlesworth