Our editors on the exhibitions they’re looking forward to this month, from Rencontres d’Arles to a Michael Haneke retrospective

Les Rencontres de la Photographie d’Arles

Arles, France, 7 July – 5 October

Arles 2025 opens under the loaded theme of Disobedient Images and brings together over 60 presentations of works by photographers from around the world. But the disobedient bit doesn’t appear to be so much of the shouty kind. Rather, there’s an overall sense that what’s on show persistently refuses to sit still. Which, since we’re talking about photographs, might sound odd, but you’ll see what I mean in Todd Hido’s The Light from Within (in Espace Van Gogh), an exhibition of eerie American landscapes shot after the sun’s gone down – headlights and lamplights blur in the exposure, the windows of houses emit soft golden light, the air is laden with fog, and nothing quite settles. And then there’s Keisha Scarville’s series Alma (in Salle Henri-Comte), in which she recreates her late mother’s presence through layered portraits and textiles; there’s a sort of wrapping and unwrapping of bodies that plays out in this black-and-white series, and you’re never quite certain whether the artist’s grief is being bundled up – hidden away – or if the peek of skin here and there, beneath those fabrics, alludes to something more transformational. Meanwhile On Country (at Église Sainte-Anne) presents work by Indigenous Australian photographers whose images insist on other ways of seeing, belonging, being. And in Ancestral Futures (at Église des Trinitaires), a new generation of Latin American photographers dig into histories of racial, Indigenous and LGBTQIA+ oppression and violence. Disobedience comes in different registers, but here it seems to be less about breaking rules than refusing easy answers. Fi Churchman

Fiona Tan: Monomania

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 4 July – 14 September

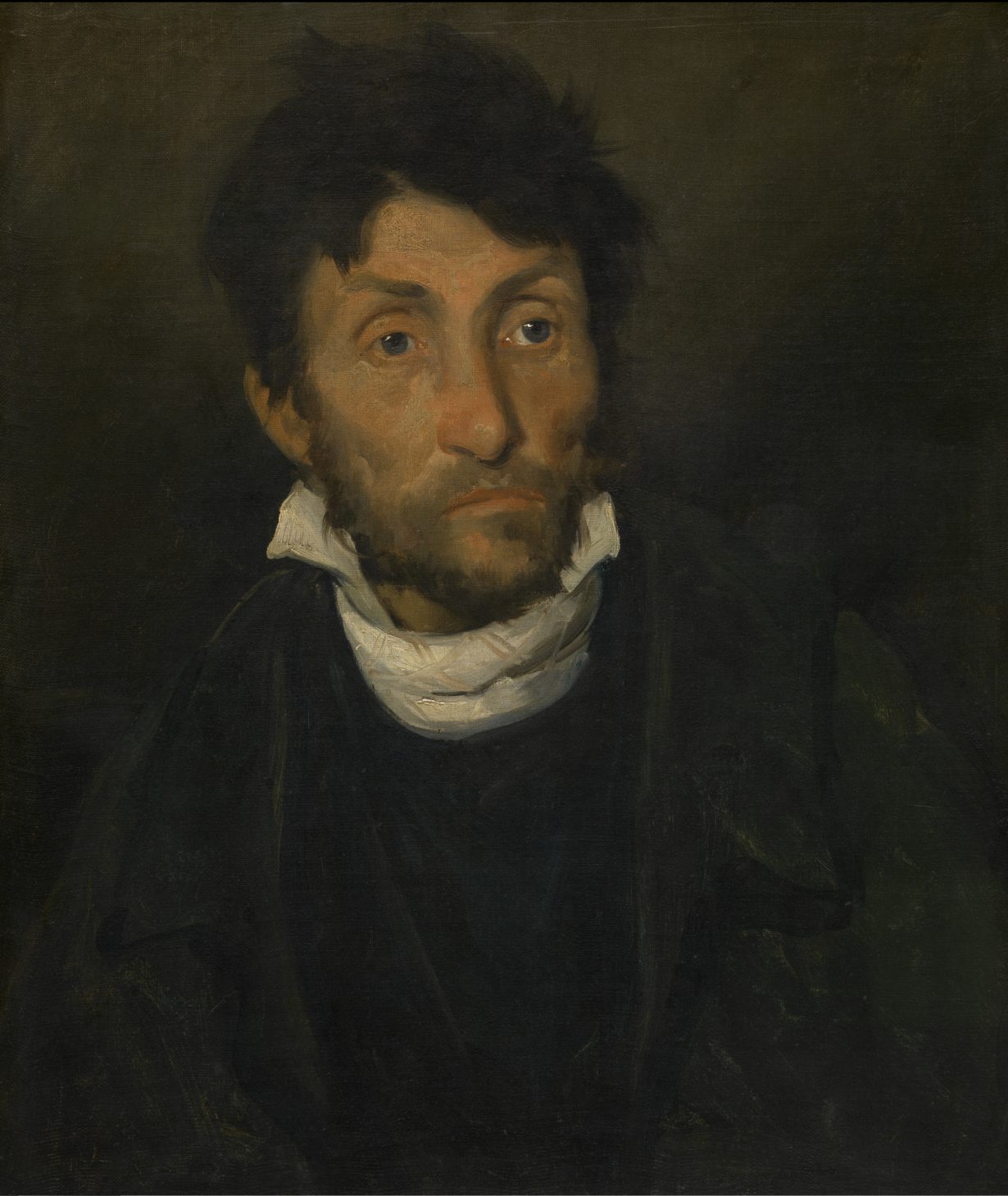

How do you even begin to approach a collection as large as the Rijksmuseum’s, with more than a million objects in storage? Indonesian-born artist Fiona Tan – who has made a name for her herself with intensive historical research into subjects as varied as early mugshots of pickpockets and a failed attempt by a Belgian lawyer to index all human knowledge at the turn of the twentieth century – is the first artist to be invited to curate an exhibition based on the museum’s archive. Tan is interested not just in figures at the margins of society but in the structural conditions that lead them there. At the Rijksmuseum, one painting opens the show. Théodore Géricault’s Portrait of a Kleptomaniac (1820–24) was part of a series of ten portraits of people confined to a madhouse, made for the psychiatrist Étienne-Jean Georget. The unnamed subject looks beyond the frame, his face and unkempt hair rendered in rough, rapidly drawn brushstrokes; it is a study in compassion, his face resigned even as his eyes glimmer with some faraway hope, whether real or fantastical. Tan extends her fascination with Géricault’s series to a deeper examination of the ways in which artists and scientists in the nineteenth century sought to understand the human psyche, exploring how observational techniques were used as a means of diagnosing mental illness. Medical textbooks, mannequins, masks and embroideries made by female inpatients are all on display, bringing the work of artists, scientists, psychiatrists and patients together to offer perspectives on what life in a mental institution at the time was really like. In doing so, she highlights the highly charged line between observation and voyeurism, empathy and abuse – depending on who, exactly, is doing the looking. Louise Benson

12th SITE Santa Fe International: Once Within a Time

Various venues, New Mexico, 27 June – 12 January

Curated by Cecilia Alemani, the 12th SITE Santa Fe International features some 300 works made between 1926 and today, by 71 artists including Ali Cherri, Sky Hopinka, Mire Lee, Simone Leigh, Wael Shawky and WangShui. The exhibition, which marks the return of the Southwestern US biennial, last seen in 2018, expands from the galleries of SITE Santa Fe to over a dozen other local venues, ranging from hotel rooms and a former foundry to a cannabis shop. It takes its title from Once Within a Time (2022), a psychedelic and allegorical film by Godfrey Reggio. Shot during the COVID-19 lockdowns using miniature sets and handmade vignettes, the film depicts, among other surreal imagery, children inside an hourglass staring listlessly at their smartphones and wandering through the wastelands of a world ravaged by climate change. According to Reggio, the film is a warning that we have unwittingly ‘exited reality’ and begun living in a bacchanal ‘fantasy world’ – thanks to, it is implied, the advent of networked technology. But rather than read the fantastical scenarios in Reggio’s films as straightforward and potentially cynical negations of the real, Alemani asks how fantasies can in turn be used to ground us in reality, connecting us to our physical surroundings and to each other. As a thought experiment and collective exercise, she invited artists to interpret Santa Fe’s history through the biographies and narratives of 20 local legends including La Malinche, N. Scott Momaday and Cormac McCarthy, to produce a sprawling saga of historical fiction, a shared fever dream. Jenny Wu

Connecting Thin Black Lines, 1985–2025

ICA, London, 24 June – 27 September

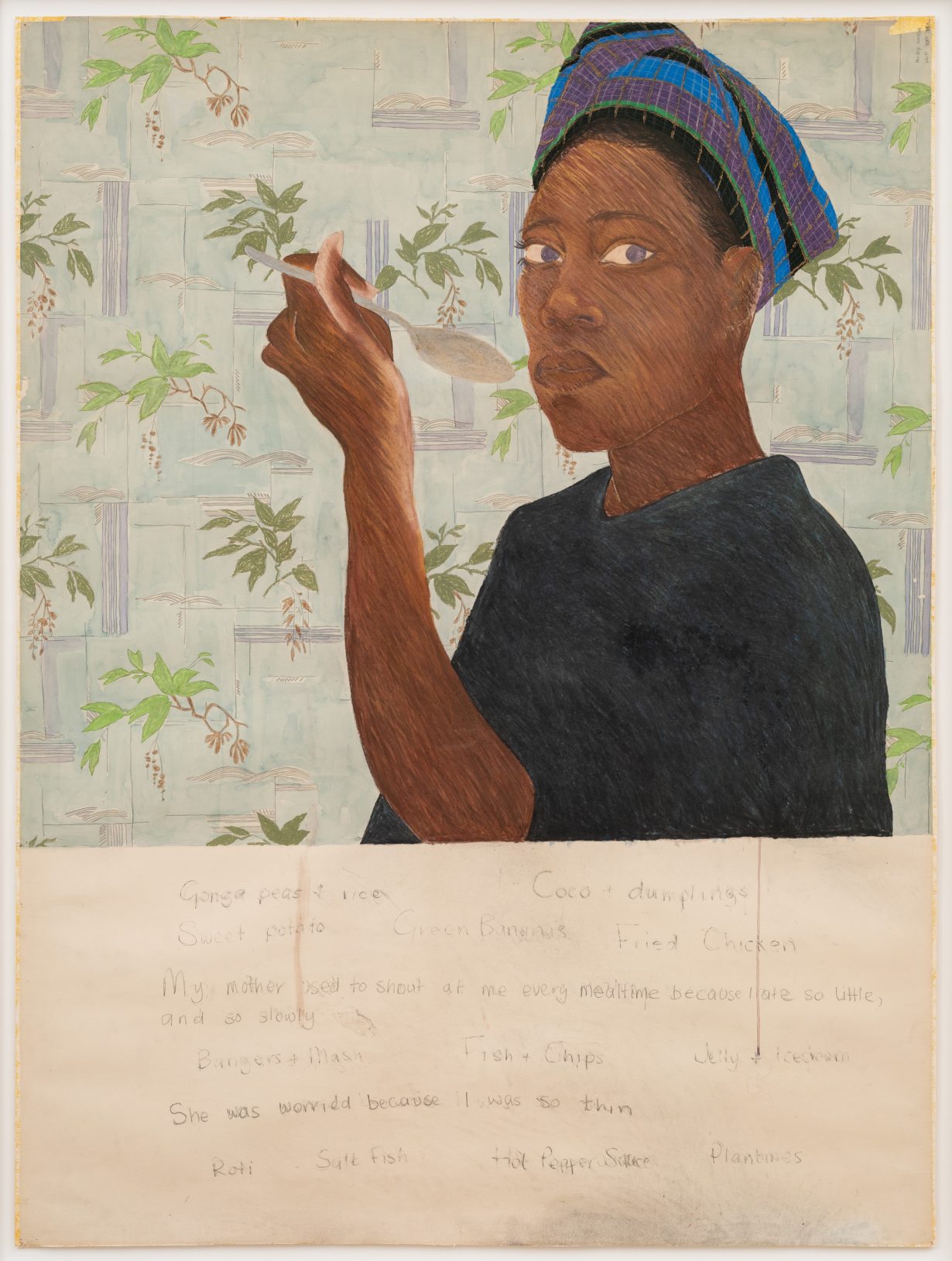

In November 1985, Lubaina Himid curated The Thin Black Line at London’s ICA, an exhibition gathering together the work of ten Black and Asian women artists – including Sutapa Biswas, Claudette Johnson, Marlene Smith and Ingrid Pollard – alongside that of her own. Denied use of the full gallery spaces, they instead lined a hallway, creating the ‘black line’ of the exhibition’s title. ‘I think that what I intended for the show’, Humid noted in a 2017 conversation with Smith, ‘was not necessarily for it to be talked about in the press, but for it to continue strengthening the conversations and for the artists in the show to keep talking to each other.’ (Waldemar Januszczak, insightful as ever, labelled the show ‘angry’ in The Guardian, while Arts Review, as this publication was then titled, was one of many that didn’t cover the show at all.) Forty years later, the 11 artists return to exhibit together and show artworks from across the decades, continuing the conversations and this time taking the entire ICA space. Accompanying the show is a busy schedule of readings, screenings and events that evidence the wider discussions and community that this group of artists has shaped and inspired, including screening of works by Helen Cammock and Pratibha Parmar, and events with writers Andra Simons and Alice Walker. Chris Fite-Wassilak

Jessica Vaughn: Cognitive Fatigue

David Peter Francis, New York, 20 June – 26 July

The United States Postal Service’s Informed Delivery updates are some of the saddest emails you’ll receive. The messages contain images of inbound letters and parcels, previews of what’s coming to your mailbox, the bulk of it being, of course, credit card promotions and alumni magazines. The Brooklyn-based artist Jessica Vaughn’s solo exhibition Cognitive Fatigue at David Peter Francis features a work titled Mail (2025) that presents a montage of these USPS scans on a small screen reminiscent of a home security interface. The banality and ubiquity of our tracking and surveillance systems seems to be the subject of discussion here. Another screen mounted just outside the gallery’s entrance livestreams 24-hour footage from the building’s roof, where Vaughn has painted two murals based on illustrations in government reports on workplace diversity, documents that themselves compress individuals into data and metrics to be monitored and modulated. Meanwhile, large aluminium panels on the walls are printed with medical impairment charts and a schematic of hands opening, closing and rotating as if performing carpal tunnel exercises. The objects here feel abandoned as much as they are being showcased. On the floor lie piles of old cubicle dividers that no one appears to be returning for. Yet the space is alive: every few seconds, an air compressor that makes up part of Vaughn’s kinetic sculpture Plenum (2025) ‘exhales’ into a spirometer, rousing one of three plastic balls inside the humble medical device. Like Informed Delivery, the process is automated and promises to repeat forever. For whom is the machine operating, Vaughn seems to ask, and why is it having trouble breathing? Jenny Wu

Claudio Cretti, Manuel Brandazza and Raphaela Melsohn: Corpo de Prova

Galeria Marília Razuk, São Paulo, 26 June – 16 August

Corpo de prova, literally ‘test body’, is an engineering term for a sample block that is used to evaluate the strength and quality of a given material (usually concrete). This process is burlesqued by curator Camila Bechelany in an exhibition of work by artists Claudio Cretti, Manuel Brandazza and Raphaela Melsohn. The body is felt both in form – all three sculptors’ works, ranging from the assemblages of Cretti, Brandazza’s sequinned and stuffed textiles and Melsohn’s ceramics, can be read as approximations of the human body – and in their haphazard making, with each artist seemingly tentative and resisting finality as they test out their materials. Brandazza’s stitching and beading of his fantastical forms is visible and clearly by hand; Melsohn has pinched and squeezed clay into long pipelike shapes. Cretti’s sculptures have the feel of ad hoc tools, a ‘gambiarra’ quality (the Brazilian Portuguese word for improvising a solution to a problem). One work from Cretti’s 2025 Trens de Mauá series features a white rocky form balanced on a cobbled-together tripod; one of the legs is shorter than the other so rests on a stone. On top of this amalgamation balances a curved stick, which ends in a netted club: a tool or weapon for an unknown purpose. The tying, balancing and stretching continues throughout Cretti’s work in an exhibition that resists notions of resolution. Oliver Basciano

Folkestone Triennial

Various venues, Folkestone, 19 July – 19 October

When this writer moved to Folkestone from London 16 years ago, being marked out as a ‘DFL’ (a ‘down from London’) was a sort of mild pejorative, cast about jokingly by locals to denote the odd city types newly arrived, with their metropolitan attitudes and tastes. Now everyone here seems to be a DFL. There’s even a local beer called DFL, which is like cultural appropriation, or something. Folkestone’s regeneration-driven transformation – from conservative declining English seaside town (play Morrisey’s Everyday Is Like Sunday for the mood) to rejuvenated if rough-edged hipster hub (see also Margate) – has a lot to do with the Folkestone Triennial, a mostly outdoor public art festival, started in 2008 and now in its sixth edition. Previous editions were curated by old hands Andrea Schlieker and (for the last three editions) Lewis Biggs, and with each edition works by the like of Yoko Ono, Antony Gormley, Tracey Emin, Lubaina Himid and Paloma Varga Weisz were retained, permanently added to the townscape and beachfront. This year the reins are taken up by Sorcha Carey, director of Edinburgh’s Collective gallery and until recently the director of Edinburgh Art Festival. If Schlieker’s and Biggs’s editions tended to circle around the themes of Folkestone’s relationship to its recent past, to national culture and to the forgotten world histories that have variously flowed through it, Carey’s edition, How Lies the Land?, looks set to tap into deep time, drilling (metaphorically) further into ideas of the land and landscape, with geology, archaeology and ecology featuring prominently in the promotional blurb. Though details of the works remain under wraps, the artists involved are of the sort concerned with an earthier and more connected take on society and its planetary context – from the archaeological sculptings of Dorothy Cross and the retro-mythical carnivalesque of Monster Chetwynd’s performances, to Emeka Ogboh’s multimedia ruminations on migration and globalisation and Cooking Sections’ investigations of the socio-ecological politics of food. As Folkestone finds itself on the fault line of big political forces – being the closest geographical point to a now-Brexited Europe, and the shore onto which small-boat migrants frequently land – How Lies the Land? looks set to present a vaster, more impersonal view of human place and belonging even if, trudging back over pebbles and sand, the contours of the future may be harder to make out. J.J. Charlesworth

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook: The Bouquet and the Wreath

MAIIAM, Chiang Mai, 26 July – 25 May

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook looks death in the face: literally, in the case of video I’m Living (2002), in which the Thai artist performs a ritual of laying various colourful dresses upon the corpse of a young woman; and in The Class (2005), where she delivers a series of videoed seminars about death to a classroom of corpses laid out on metal mortuary stretchers. These encounters are the result of her collaboration with morgues. It’s not totally morbid though – Rasdjarmrearnsook approaches her work with tender reverence and a wry sort of humour, treating the dead as if they were still alive. She is fully aware of the absurdity of lecturing the dead about a subject they’d be better experts at. The breadth of Rasdjarmrearnsook’s multidisciplinary practice will be on show at MAIIAM’s survey exhibition, which spans four decades of print, sculpture, photography, performance and installation that explore themes around the female body, personal agency, voicelessness, nonhuman relations, art history and its pedagogies, and, of course, death. She is interested in acts of communication, and conversely, miscommunication. Whether that’s in Great Times Message, Storytellers of the Town, The Insane (2002), a multichannel video installation for which the artist interviewed patients (ostracised and treated as taboo subjects) at a Thai asylum, allowing them to voice and narrate their experiences; or in her Two Planets (2008) video series – reproductions of famous Western paintings installed outdoors in rural Thailand, to which villagers responded with humorous and irreverent commentary. “Why did she take off her clothes?” a woman asks, perplexed by Manet’s naked model sitting in the company of the dressed men in Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1863, to the titters of her fellow viewers. Why indeed. Fi Churchman

Complicit: A Michael Haneke Retrospective

Barbican, London, through 27 July

Sick of all your neighbours prancing around in Birkenstocks, grinning like idiots and high as kites on summer serotonin? Why not let Austria’s Palme d’Or-winning film director Michael Haneke offer an antidote to the seasonal sunny disposition and bring it all back down to reality, during this festival of unexpurgated misery, aka a season of his films. In deeply disturbing works such as Funny Games (1997), Caché (2005) and The White Ribbon (2009), the Austrian director explores the ways in which violence, guilt and alienation inevitably disrupt our illusions of societal solidarity and unity. And the myth of the fundamental goodness of humanity. When he’s not doing that, he’s exploring how we deal with decrepitude (Amour, 2012), emotional and sexual repression (The Piano Teacher, 2001) and bureaucratic nightmares (The Castle, 1997). It’s Haneke’s keen eye for the warning signs of individual and social collapse that continue to make him one of Europe’s more important filmmakers of recent decades. Warning signs that seem ever present in our current turbulent times. Nirmala Devi

Eve Tagny: In the Underbelly of a Kernel

Westfälischer Kunstverein, 5 July – 5 October

When I was a boy, I would occasionally help my grandfather out at his allotment. To cross the beds of potatoes and gooseberry shrubs, I’d stretch my legs out to reach old clay tiles that had been laid out as stepping stones. Working the earth as he did always required both hard graft and a delicate touch. In 2022 at Toronto’s Cooper Cole gallery the Montreal-based artist Eve Tagny installed Untitled (2022), a horseshoe-shaped fixture of 90 ceramic tiles laid across a straw and soil bed. Some contain inscriptions of text set into the unglazed surface like poetic flashcards (‘one are was initially left out / of the area’s development dynamic / Parc-Extension’, one tile reads, alluding to the Montreal neighbourhood), while others held small pieces of torn and dyed material, a frayed hairband or a spare piece of cotton wool. Much of Tagny’s work looks at the material traces of history, in turn transforming these into signifiers of memory, particularly those related to nature and land. Such rural places are often politically charged – whether neglected by governments, subject to invasion by imperial powers (as Tagny’s work notes) or mythologised in community lore. Tagny’s Untitled work, alongside a series of abstract portraits taken across urban and rural settings, began to reinscribe those affects onto the material world. This show of new works at Münster’s Westfälischer Kunstverein will continue the pre-lain path. Alexander Leissle