Our editors on the exhibitions they’re looking forward to this month, from Wolfgang Tillmans and Momentum 13 to Marina Tabassum’s Serpentine Pavilion

Marina Tabassum: A Capsule in Time

Serpentine Pavilion, London, 6 June–26 October

Normally, like a fly that a small child has stripped of its wings, when architecture becomes part of the content of a museum or gallery it does so to die. Stripped of its function it’s not quite clear what it’s supposed to do, unless you’re one of those people who enjoys plans, sections and models; who enjoys pulling things apart to see how they work. The basic premise of the Serpentine Pavilion, an annual commission now in its 25th incarnation, is to display architecture with its wings (or function) still attached. Dhaka-based architect Marina Tabassum is best known for projects such as the Bait Ur Rouf Mosque in her hometown and the Khudi Bari, a portable, low-cost, modular dwelling on stilts designed, during the pandemic lockdowns of 2020, for (often displaced or marginalised) people living in the flood plains of Bangladesh. All that might seem a far cry from designing what is often reduced to a fancy corporate hospitality tent in one of London’s royal parks, but Tabassum (who, when she’s not designing such structures, frequents Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world lists) is promising to use the opportunity to continue to pursue her interest in how architecture can respond to the ephemeral and impermanent, as opposed to the forever-structures and monuments that most people (and most architects) generally associate with the profession. Her pavilion, titled A Capsule in Time, is a semi-open, wooden structure (apparently inspired by South Asian tent designs) that looks like half a pill capsule, further dissected and built around a semi-mature Ginko tree at its centre. The translucent structure engages with the shifting qualities of light and shelters a stage-like space that remains open for activation by the public throughout the day and night. Except, presumably, when it’s hosting a VIP event. Nirmala Devi

Hiền Hoàng: Garden of Entanglement

FOAM Amsterdam, 6 June–ongoing

Hiền Hoàng’s latest exhibition at Foam, Amsterdam, titled Garden of Entanglement, sees the Vietnamese-born, Hamburg-based artist present three recent projects, Garden of Entanglement (2024), Scent from Heaven (2023) and Across the Ocean (2021–2024). Each of these traces how trauma leaves its imprint not only on our human bodies and histories, but on the natural world too. The titular installation work (developed in collaboration with scientists in Florence and Kassel) includes a soundscape and floor panels on which visitors are invited to lie down, to experience and connect with the subtle sounds and vibrations emitted by trees. Presented here as witnesses, these trees absorb the slow violence of colonial expansion and environmental degradation. Meanwhile, Scent from Heaven turns to the Agarwood tree (in VR and multisensory format), whose rare earthy fragrance – associated with healing, purification and transcendence in traditional medicine and spiritual practices across Southeast Asia – emerges only through infection or open wound. The work lingers on this paradox: healing and redemption are what humans desire, it suggests, but at what cost? Across the Ocean, which comprises a series of photographs and videoed performances, shifts to more personal ground, ‘examining how food serves as a bridge between culture and personal memory while also being a vehicle for stereotypes and clichés’. Through food, Hoàng reflects on the dislocated identities of migrants and the diaspora, the ways in which cultural memory is both preserved and distorted in transit. The way, for example, foods like rice, soy sauce, and other staples perform as shorthand for ‘Asianness’ in the Western imaginary. Hoàng’s colourful and uncanny photographs and performances that blur the boundary between foodstuffs and the female body offer a sharp indictment of the ways in which cultural identity is commodified, consumed, and flattened into stereotype. Yet, across these works, Hoàng doesn’t seek resolution. Instead, she traces transformation as a slow, often painful unfolding – one marked as much by rupture as by renewal. Fi Churchman

Wolfgang Tillmans: Nothing could have prepared us – Everything could have prepared us

Centre Pompidou, Paris, 13 June–22 September

Forty-nine and a bit years after it first opened its plateglass doors to the public, Paris’s Centre Pompidou is closing in September for a major restoration project of its iconic building, designed by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers in 1977. All the steel trusses, multicoloured roof-mounted ventilation ducts and snaking external escalators – all the stuff that made the Pompidou look like a very cool spaceship just arrived from the pages of Métal Hurlant – are worn out, and in urgent need of a fix up. But just before the builders move in, the Centre is handing over the 6,000sqm of level 2 – home to the Bibliothèque Publique d’Information -–to artist Wolfgang Tillmans, to do as he will, giving him ‘carte blanche’, as the French like to put it. The library is an appropriate venue for the celebrated photographer, who since emerging from the vibrant style culture of the 1990s has become a chronicler of the world seen from the point of view of the generation that came of age after the Cold War, with Tillmans’s lens a celebration of the energy of everyday life, and the lives lived in youth culture and its subcultures. In the last decade Tillmans has increasingly turned to presenting his work as a constantly revised archive, while relating his own photography to trestle tables filled with documents, images and texts drawn from the mass of everyday media – newspapers, magazines, press releases, official documents, and examples of his own work found in magazine editorials through the decades. Nothing could have prepared us – Everything could have prepared us will entwine four decades of Tillmans’s work with the library’s more formal regimentation of knowledge. It’s a punctual moment to be staging a retrospective when your work is synonymous with a historical period that was marked by liberalisation and globalisation. Tillmans, never shy to put his name behind campaigns extolling the merits of European togetherness, looks set use the opportunity to reflect on the unravelling of that old order, and the troubled new era we’re now entering. J.J. Charlesworth

Arthur Jafa/Mark Leckey: Hardcore/Love

Conditions, Whitgift Centre, Croydon, 28 June–10 August

Mark Leckey once claimed that the most exciting art form was the music video. In the age of infinite scrolling, Leckey’s perspective on the creative potential of new media has proven prescient. In 2025, it is telling that his 1999 film Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, with its spliced video footage of nightclub revellers and amalgamated sound, feels strikingly contemporary. In typical Leckey fashion, the work pairs joy with a pervasive sense of melancholy – what the artist has called ‘sweet-sadness’ – and a heightened awareness of the inevitable march of time. It is that same sweet-sadness that runs through Arthur Jafa’s Love is the Message, The Message is Death (2016), a fast-moving progression through a succession of images and short clips from a swelling, hugely varied range of sources – from silent films to phone footage of police violence to the artist’s own home movies. A reflection on the African-American experience, Jafa expands the music video format (the work is accompanied by Kanye West’s ‘Ultralight Beam’, 2016) to reflect the often-fragmented experience of the digital age, when humour and crisis can exist side-by-side. That the two works will be screened together for the first time this month at Conditions, an artist-run project space and studios located in a shopping centre in Croydon, points too to the mutability of the music video, moving easily between the television, the phone, the gallery and, yes, even the mall. The exhibition is the idea of art dealer Gavin Brown, a longtime friend of Leckey’s (it was to Brown that Leckey proclaimed the artistic potential of the music video; Brown responded by asking him to prove it, and Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore is the result, or so the story goes). Louise Benson

Tiago Mestre: Fogo Fumo

Gomide & Co, São Paulo, 7 June–9 August

There are a few lines I keep coming back to in Ivo Andrić’s novel The Bridge Over the Drina (1945), which I’m currently reading. He describes the drunks in his home town as they slowly fall into a stupor: ‘They were lovers of shadow and silence…. They sat there and drank, and while drinking waited until that magical light which shines for those completely given over to drink should at last burst upon them, that joy for which is sweet.’ It is a scene that resonates with Tiago Mestre’s ceramics: drunk vessels of burnt ruby brown in the long tradition of the Alentejo, where the Portuguese artist was born. These pitchers, jugs, jars, amphorae, bowls, cups and mugs seem to have a kind of reflective sentience, yet their shape is warped, slumping and collapsing as if infused with the effects of the beer and liquor they imaginatively could contain. There’s a slow melancholy to them. Mestre, taking reference from the tasca, the cellar and the shop – timeless places to waste time – will hang his inebriated sculpture across a metal bar dissecting the gallery, the light playing on the crevices of each work, changing its form as the day passes through the window. Alongside the vessels, he will install a collection of elongated, snaking smoking pipes, warped ceramic versions of the clay pipes the artist found washed up on the riverside in London, the shank and stem stretching out and undulating as marked by the time passed since their last smoke. Oliver Basciano

MOMENTUM13: Between/Worlds: Resonant Ecologies

Moss, Norway, 14 June–12 October

Why spend time talking about the nonhuman when you can try listening to it? While the 13th edition of Momentum has a vague ecological theme, Danish curator Morten Søndergaard has veered this edition of the Nordic biennial to the aural, to highlight more about how we engage with the world around us. Alongside some of the usual sound art and biennial favourite names (like the rooms full of speakers from Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller; the slacker-guitar videos of Christian Marclay; the meta-techno of Carsten Nicolai; and whatever old project Douglas Gordon has recycled lately) the project brings together a disparate group of artists and academic researchers, predominantly from northern Europe, to create sound installations across the fjords and forests of Moss. There are works from Oshima Takuro, who has mapped out urban space with a hybrid skateboard-guitar, and creates haphazard live performances from assemblages of found materials and prepared instruments, to the aquatic videos and performances of Juan Pablo Pacheco Bejarano as he explores the overlapping myths of the Atlantic. Chris Fite-Wassilak

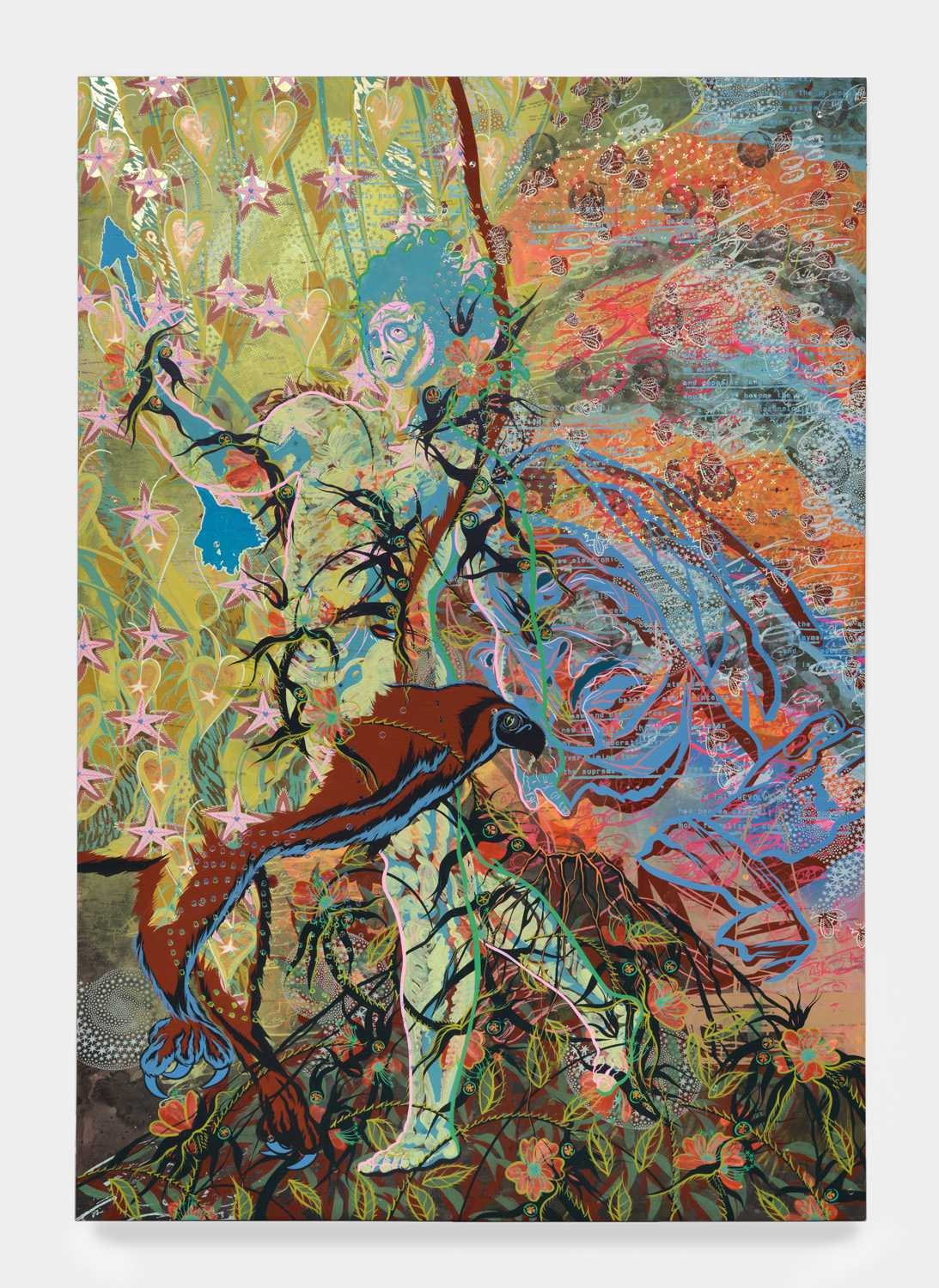

Tammy Nguyen: A Comedy for Mortals: Paradiso

Lehmann Maupin, New York, 5 June–15 August

In 2021, Tammy Nguyen produced a series of artist books titled Four Ways Through a Cave, several of which were made with multiple spines, allowing one to open like an accordion, another, to borrow her words, like a ‘geological formation’ and yet another like ‘the wings of a bird’. The paintings and prints on parchment exhibited in A Comedy for Mortals: Paradiso, the artist’s first solo show with Lehmann Maupin in New York, can likewise be read as texts with multiple axes. For one, the surfaces of paintings like O Good Apollo (2025) and intaglio prints like O Fruit Created Ripe (2025) are literally pocked with rubber-stamped words and layered with handwritten phrases. These works, which are dense with faces, symbols and vegetal motifs that point – often delicately and obliquely – to episodes in twentieth-century geopolitical history and present-day ecological concerns, pivot on Nguyen’s loose and introspective interpretations of canonical Western narratives such as The Divine Comedy (c. 1321) and Frankenstein (1818) and publicly accessible documents like Dwight D. Eisenhower’s farewell speech to the American people, in which the outgoing President warned against the establishment of a military-industrial complex. Her painting Absorbed in the Object of His Delight (2025), on view at Lehmann Maupin, juxtaposes the green face of Frankenstein’s monster with blood-coloured stamps of Eisenhower’s portrait, an allusion to ‘atomic technology and the ongoing threat of destruction’ and a reminder of Nguyen’s political commitments. Jenny Wu

Gala Porras-Kim: The Categorical Bind

Sprüth Magers, London, 4 June–26 July

Last time I spoke with Gala Porras-Kim she was busy trying to contact the dead. Her precise communication method was ‘encromancy’, an early form of ink divination, and she was trying to reach the first-century BCE citizens of Shinchang-dong, an area of present-day Gwangju (or at least their spirits), to ask if they were happy in the knowledge that their material remains were on show in the city’s National Museum. This is the Colombian-born, US-based artist’s modus operandi, a kind of institutional critique, specifically dealing with issues of museum ethics, operations, ownership and restitution, in a practice that is never dry or hectoring. It has won her fans, especially in the museum world, precisely because she is dealing with many of the thorny issues that museum workers are themselves thinking about. For her current solo exhibition at Museo della Civiltà Romana, Rome (though 1 October), she interviewed the institution’s curators as they handled the object they felt closest to; the resulting videoworks leaves only the hands (with the objects and the rest of the interviewee’s bodies removed) to create portraits of care and intimacy. In another current solo show, this time at Carnegie Museum of Art (though 27 July), she turned her attention to the museum inventory, questioning how objects are labelled and categorised, how some are regarded as art and others ‘artefacts’. For her first solo show at Sprüth Magers, expect similar challenges to epistemological conventions. Oliver Basciano

Redrawing the Boundaries: Art Movements and Collectives of the 20th Century Khaleej

Hayy Jameel, Jeddah, through 13 October

The first bit of boundary redrawing in this wideranging survey show comes from the fact that it features work drawn from 20 collections across the Gulf and broadly covers the development of Modern art in Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (collectively, the Khaleej, or Arabian Gulf). Broadly speaking the works on show (by over 50 artists and collectives) span the twentieth century period when most of those nation-states were coalescing into the formations in which we know them today. Another part of the redrafting exercise takes inspiration from the late Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor, and his efforts to insist on the existence of regional discourses and histories that were for most of the course of Western art history considered not to be on the map, a form of terra incognita that wasn’t even worthy of being labelled as such. In keeping with that geographic rebranding, some of the emphasis here is on the fact that modernity in the context of art was shaped as much by influences from the East (and South Asia in particular) as it was from the West (where the nonsense of art history was ‘invented’). The idea, then, is that it gets reinvented here (the show is curated by art historian Dr. Aisha Stoby as a sequel to a 2022 show she curated at NYU Abu Dhabi). Among the artists on show, you’ll likely recognise names such as Abdul Nasser Gharem, Ahmed Mater and Hassan Sharif, but the fun will more probably lie with those works by all those names you don’t. Nirmala Devi

SXSW London

2-7 June

When Alfred Hitchcock was working on North by Northwest (1959), it’s hard to imagine he could foresee inspiring a music-cum-film-cum-tech-conference bonanza in Austin, Texas. Almost four decades after its inauguration, SXSW makes its debut in London, filling Shoreditch with conference talks, gigs, film screenings and other nebulous ‘activations’ for the first week of June. There are no diving planes here, nor anyone as handsome as Cary Grant (though I wouldn’t rule out ad-men on the run). There is, however, some contemporary art. Beautiful Collisions at Christ Church Spitalfields will survey the impact of diasporic Caribbean artists on London’s cultural development, featuring works by Alberta Whittle, Tavares Strachan and Alvaro Barrington; LDN LAB promises to explore the ‘transformative place where the arts and technology meet’, so that means Beeple, Holly Herndon & Mat Dryhurst and… Andy Warhol (I hear shouts of bingo at the back). I’ll be sat for a screening of La Guitarra Flamenca de Yerai Cortés (2024), a documentary connecting the music of the Flamenco guitarist Yerai Cortés with his family heritage in the Iberian Romani community, in doing so reflecting upon the genre’s own links to this broader heritage. Cut loose at 93 Feet East with the Bahraini duo Dar Disku, whose DJ sets meld Gulf music traditions with the UK music scene they’ve recently made their home. Or, just take your photo with the Premier League trophy at the Truman Brewery Sky Glass Expo Stand and be done with it all. That one’s for free, while passes for the week range from, ahem, £595 to a knee-shaking £1,300. Alexander Leissle