Silent stadiums, ‘audio carpets’ and cardboard fans – what has the pandemic done to the game?

On the day after my team, Liverpool Football Club, has won the English top division for the first time in 30 years, I can confirm: the beautiful game? Still beautiful. The happiness and excitement and almost unbearable joy I felt last night was everything I ever imagined it would be. But the game didn’t look like anything I knew.

The day before Liverpool’s last game at its home stadium Anfield, fans decorated Spion Kop, the stand where the team’s most ardent supporters sit. They filled it with homemade signs – about the team’s history, its manager, images of players and the club’s symbols. Nearest to the pitch, a huge wide banner read, ‘And now they’re gonna believe us’: a chant some fans have been singing since at least December – hesitant not to jinx it, but the team has been on top of the league all season. It continues: ‘We’re gonna win the league’. It’s been months since.

It’s been months because the Premier League, and all other leagues in Europe, were halted due to COVID-19. And when it came back, no one knew what it would feel like. It came back to empty stadiums, save for a few journalists allowed in, who have been sharing images and videos of the grounds before and after games, desolate and haunting. The empty seats not used by the substitutes, who sit socially distant from one another, are covered in huge vinyl sheets, masking the sad, void, haunting stadium seating. There are other solutions to the problem of emptiness: at Watford Football Club in England, the scarves unsold at the gift shop were placed on the seatbacks. Thousands of cardboard cutout fans filled the Borussia-Park stadium in Germany, a CGI crowd at the final of the Italian Cup in Rome last week (the match also featured a self-serve medal stand), an unfortunate attempt at FC Seoul who (accidentally) seated sex dolls in their empty stands, and the many fans’ faces at home and broadcast live via Zoom on advertising and score boards.

The first time that I saw a game played behind closed doors because of COVID-19 was on 8 March, when Juventus of Turin faced Inter Milan – it was supposed to be a title decider, but it didn’t feel like one. I was expecting it to be weird; I have always associated football with the presence of a crowd. But I was more surprised not by the sadness of the sight of empty stands, but by the stillness. The huge cement stadiums become echo chambers where the shouts of players and managers reverberate through the stands. Juventus won 2-0. The urgency that disappeared in the empty stadium was foretelling of the pace of the league which would come to a halt: the next day, football stopped in Italy. And in Germany, Spain, France, England, and everywhere else in Europe. The only league that kept playing was the Belarusian Premier League. It won some new fans.

To hear the ball hitting players’ feet feels naked, unnatural, exposed. And so, when the German football league restarted in mid-May, broadcaster Sky Deutschland began dressing the game with an artificial crowd soundtrack. Alessandro Reitano, the station’s senior vice-president of sports production, explained to ESPN how it was made: an ‘audio carpet’ is created for every game – 90 minutes of crowd noise from a previous match between those two teams, which an engineer completes live, editing in additional shouts and grunts based on events in the game.

The German audio engineers working on these crowd soundtracks described playing football video games in order to understand how artificial sound operates in the context of viewers’ expectations. Sound in these games, however, is directly triggered by what players are doing on the console. There is a cause-and-effect. An expected system. There’s something melancholy about the sound of tens of thousands of people that doesn’t feel spontaneous, raucous – the work of a lonely sound engineer embellishing last-year’s audio. It’s a sound that will surely become emblematic of this time. The football that viewers see on television is far from what they knew before, and to make it more familiar to them, television channels are repackaging viewers to themselves – a sound file of memories.

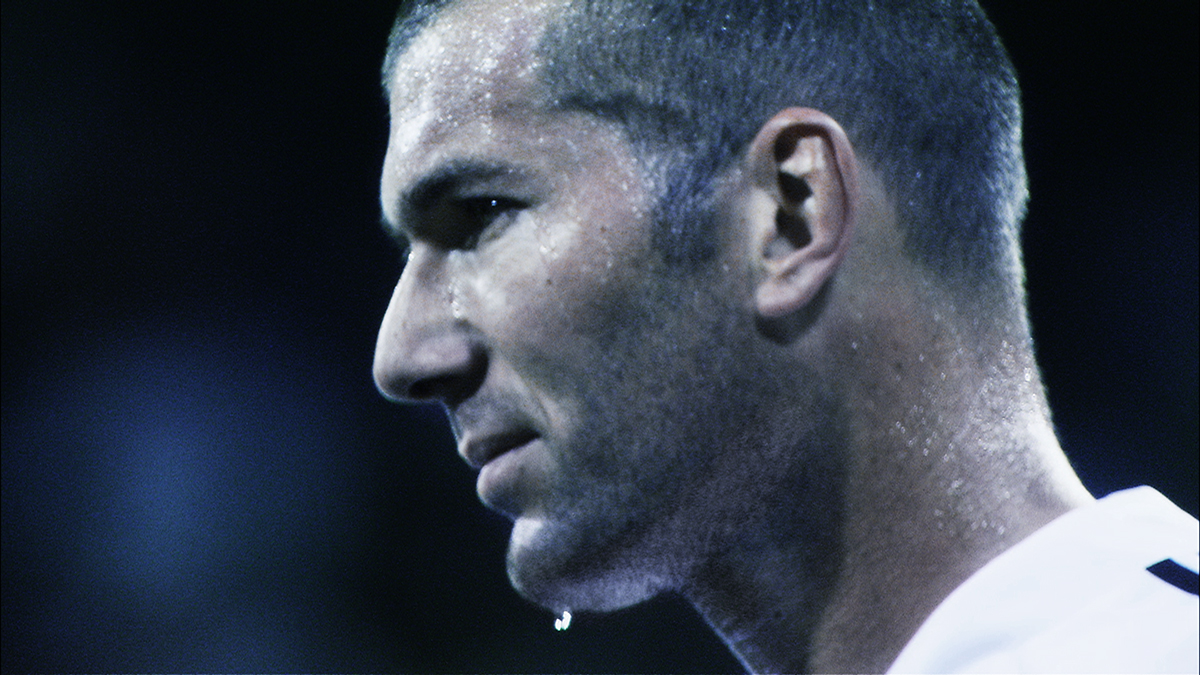

‘When you are immersed in the match, you don’t really hear the crowd. At the same time, you can almost choose what you want to hear. You are never alone. I can hear someone shift around in his seat. I can hear someone cough. I can hear someone speak to the person next to him. I can imagine that I hear the ticking of a watch.’ The man speaking is French football legend Zinedine Zidane, in an interview accompanying Philippe Parreno and Douglas Gordon’s film Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait (2006).

A 90-minute portrait of the player shot using 17 synchronized cameras across the length of a single match (Real Madrid v Villarreal, 2005), watching Zidane is a constant shuffle between what is familiar – the green grass, the shouting fans – and what is new: the focus on a single player rather than the ball, a person not the game. ‘When you step onto the field,’ Zidane describes, ‘you hear the crowd, you feel its presence. There is sound, the sound of noise.’ Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait is an oft-cited example of contemporary art’s meeting with football. But its aesthetic system – close to the sport, yet deviating – is eerily akin to the experience of watching football now that it’s back after its COVID-19-induced hiatus. What was a familiar aesthetic experience repeated every weekend is a now a series of semblances of what is known, a meeting of memory and reality, a portrait of the time.

But football in the age of COVID-19 can often break back into reality. There were minutes of silence in memory of the victims of the pandemic in all European leagues. In Italy, doctors step onto the pitch before the games, a reminder of the country’s gratitude for the medical staff that handled one of the worst outbreaks in Europe. In England, when football restarted last week, players wore NHS badges on their kit. This was joined by ‘Black Lives Matter’ replacing the players’ names on the back – an initiative that came from the players. Footballers have also taken a knee before the start of each match, lined up along the centre-circle and halfway line – a nod to NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick, and an insistence on the place of politics in sport.

This meeting of politics, pandemic, and sport challenges every comment on football as escapism. Zidane sensing the crowd around him, the Liverpool fans leaving visual markers that stand in for real-life presence: these expose the coming-together, the ritual of football. What I thought was lost to empty stadiums and melancholic audio carpets. The sound of noise Zidane describes is the sound of memories, of excitement, of everything I know of the game. Nothing about football now is better than it was before it was stopped in March, but I can still recognize what I know: emotions, intensity, and an insistence that this love is very real. Writer Grant Farred, in his book Long Distance Love (2008) describes his love of football as an answer to a line by South African poet Arthur Nortje: ‘it is life, somehow.’ Farred responds, in words that feel apt for our times, in its mix of truth and fiction, of powerful representation and haunting absence, of memory challenged by reality: ‘But it is life, nonetheless, the only life worth living.’

Orit Gat is a writer based in London, and a contributing editor at The White Review. She is writing a book about football, If Anything Happens.