‘I’m mostly interested in art that excavates from the psyche – not the frontal lobe, not the intellectual, not the speakable, but the unspeakable’

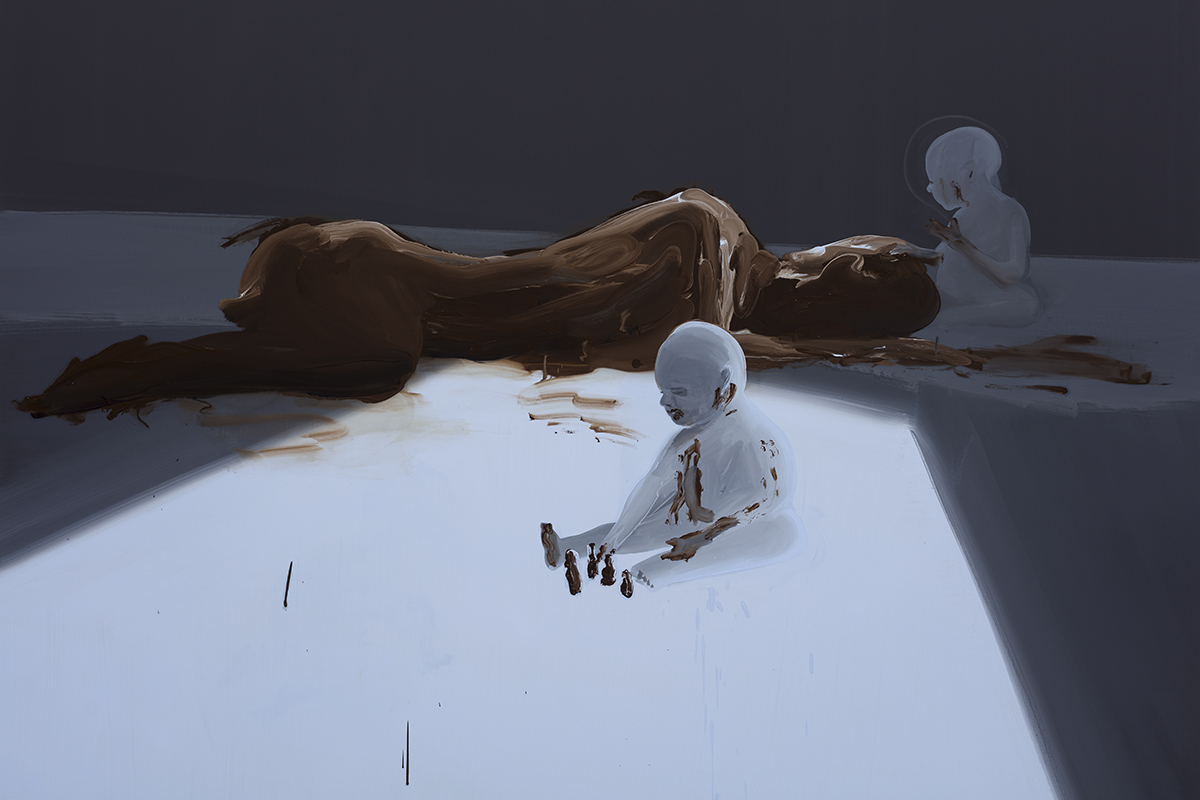

Tala Madani’s paintings depict a universe of splendid transgressions. A brood of babies feasts on a mother made of crap. A toddler wields a penis the size of a go-kart. A man is levitated by the power of his own glowing ejaculate. It’s a funny, horrifying and often hypermasculine place, animated by the mythic logic of the subconscious. To suit her subject, Madani depicts many of these activities in the dark, lit dramatically by flashlights and projectors, as if they were scenes in some sordid farce. Light is a primary force here, just as it is for all painters, but these lights are artificial, invasive beams of unwanted exposure.

Since 2006, Madani has created these paintings (and also animations) with the quick brushstrokes and informal attitude of cartoons. But behind these easy lines is a conflict with the whole programme of our socialised selves. Her buffoonish characters seem to be couriers of a bitter message about human nature.

I spoke to Madani on a videocall about these ideas and others. The feeling of the talk was comfortable enough that I questioned if the two of us had met before, but we had not. As she spoke, her voice rested at a deep, relaxed pitch, with a clear confidence that underlined everything she said, even her contradictions. Sometimes she switched midsentence into a mode of high-intellectual intensity, and began teasing out the sociophilosophical implications of her work. On a few occasions, she paused the conversation to criticise her choice of words, and after we finished, she made a few edits to her initial responses that she felt had been “un-succinct”.

Courtesy the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

Transgress Yourself

Ross Simonini Your work has a nice, transgressive bite to it. Is this a form of resistance? Would you say that you feel repressed by society?

Tala Madani If I was feeling quite repressed, I’d probably make works that reflect repression. So, in a way, the transgressive work allows me to feel quite free. But of course everyone feels repressed. I mean, right now I’m feeling repressed because of COVID, but it’s necessary.

I think you are who you are based on the first five years of your life and how you were treated and how you were allowed to be. And you live within that for the rest of your life. Trump’s behaviour might be totally indicative of how his psychology was formed from a very long time ago, but not necessarily reflective of his current position. But when you say my work is transgressive, I think my work needs to become so much more transgressive.

RS In what way?

TM To make anything, you have to really believe in it. You have to have total faith in it, at least in the moment of making it. And sometimes I wish I believed in other things than I do because I want those things to become magical to me. That’s where my own limitations are in my transgressing, the limitations of the faith that takes art from an object to a magical object.

RS So you want to transgress your own ideology.

TM Yeah, that’s the constant project basically.

RS Where do you get stuck?

TM Anything that you don’t see in my work is where I’ve gotten stuck. So whatever you see is where the faith is.

RS Do you think the limitations evolve from your childhood?

TM I think they’re based on experiences which create your connection to everything. You can’t really believe in something that you don’t know. The limitation is one’s exposure. It’s the lived life.

RS When you were a teenager, you moved from Tehran to Oregon in America. How did that affect you?

Courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias, London

TM Well, in Tehran America is perceived in a very particular way through its own cultural outputs. At that time it was Hollywood, MTV, Tom Cruise, Schwarzenegger. And then Oregon was very different to that idea of America: beautiful, but also secluded. I lived in a small town of 6,000 people, and it was a dry [no alcohol] town, which was actually like Iran… But the big shift was the surprise of how little Americans understood Iranians. Iranians were so involved with American pop culture and I thought, for no reason at all, that America would be somehow aware of Iran. So the big shock was that gap. I became much more Iranian in Oregon.

RS What did that mean?

TM In Iran, I thought I was Madonna. I wore a blonde wig and identified with things that I was watching on TV. But then when I got here, I missed home. I think Iranians are actually some of the happiest people, despite all the economic and societal problems. But they just don’t know it, because they’re not allowed to travel and see the rest of the world.

RS Why are they so happy?

TM Interpersonal relationships. I live in Los Angeles and homelessness is a huge problem here. And I think of so many people in Iran that would be homeless if they didn’t have a family net. So I just think about that dependable net that you have as an Iranian, which has disappeared in many Western cultures: family, extended family, friends.

RS Are you happy?

TM I’m happy. I mean, I’ve had coffee and I think caffeine makes you happy. So I’m happy, unless things are really terrible. I also keep the shit to myself. I don’t feel like I need to project onto you right now. This is not an appropriate venue for me to release it.

RS Well, if you need to…

TM Ah, you’re sweet. But actually, this is a new cultural norm and I’m not sure how I feel about it. Like, how do you use your own shit? How do you use your depression? How do you use those feelings? If I’m constantly releasing them, I’m not using them, and as an artist you need to use everything.

RS You don’t want to give me your fuel.

TM If I were to air these feelings and they were to go to an interesting target, that in itself would be interesting. But just to air them does nothing.

RS Is your art a way of airing feelings?

TM Possibly, for me. But it’s really hard for me to know how people read the work, because it’s purely subjective. I think generally whenever you’re faced with an artwork, film, music, you use it for your own needs and what it can do for you. But I’m not a consumer of my own work, right? So I don’t really know how that registers. I’m only interested in my own experience as I’m making it.

RS The paintings often depict a literal expulsion of fluids, which certainly suggests a release.

TM Definitely. There’s a few paintings I’ve painted where a guy has cum on a chair and then he’s shooting it with a gun.

RS Cum Shot [#1, #2 and #3, 2019].

TM That’s right. Terrible titles. But I was thinking about the sperm being half the child, and the guy’s relationship to ‘the new’ is that he just wants to shoot it down. His own relationship with the future is a bit fearful, and the minute the cum is out of him it’s no longer himself.

RS Are you thinking about this before you paint? Or is this in retrospect?

TM I was painting the Shit Mom series [2019] at the same time, with lots of children around this figure of a shit mom. And I was thinking, what is the paternal experience of that? What is the mirroring male experience of that? But these paintings are not totally pre-understood. They’re a curiosity that I followed.

New Expectations

RS Has the Trump/COVID era changed people’s interpretation of your work?

TM I think the pandemic has created so much limbo and confusion right now that it’s difficult to actually make work that is directly about something. And of course, thank God Trump didn’t get reelected. I mean, who could have ever made anything had he gotten reelected?

RS Are those internal transgressions you mentioned harder to perform during the pandemic?

TM I think whenever something is in limbo, you become conservative. You’re on a tightrope. You want to hold onto something. I think it’s really important for us, for all our sakes, to weed out strains of conservatism, because they’re rooted in insecurity and they’re rooted in fear and they get propagated because a lot of structures are comfortable with it. And if artists are invested in ideas of nostalgia, where they actually are interested in harkening – oh, that comes from that! It looks like that! Yay! It looks like this! – and celebrating, then they are not any different from Trump or Boris Johnson. Any kind of investment in nostalgia is really fighting for the same conservative positions of these politicians. And these ideas are put out there and it doesn’t get checked in the artworld. But we should expect more from cultural makers.

RS How does this conservatism manifest in art?

TM When you can’t have a direct experience with the artefact in front of you as an object, and instead you’re having an experience of it in relation to the past. But that’s very different from the way, say, David Lynch uses nostalgia. Because he’s outputting something purely fresh, challenging and compelling.

But our expectations are not ubiquitous. There could be someone who sees art for the first time. And so their experience would obviously be very different from someone who knows the history of art. But as creators, if one’s mental work is involved with nostalgia on a personal level, then you are involved with something that’s not quite different than a political ideology – which that same person might be critical of. And I think the recognition of this is important. Otherwise we’re becoming sloppy and we’re not creating a stepping stone towards something greater.

The Artist Is Irrelevant

RS Do you perform transgressions in your life?

TM Forget me! Who cares about me! It’s irrelevant! The days of ‘She paints in her underpants and that’s why the paintings are so interesting!’ need to be behind us.

RS So you probably dislike the now-popular mode of looking at someone’s art through their identity markers.

TM I think it’s a disservice to all parties involved: the maker, the work, the viewer. I’ve always fought the read of my work in relation to me being from Iran. But here’s the issue: right now, this is hot, the gender-race thing. It might not be hot in ten years. But the work is the work. The paintings become entities. They become personas. They become objects with souls. They become something outside of anybody who made them. That’s the idea of transcending for a viewer. Now, if I’m going to pull you down with my personal stuff, you’re not transcending anything. I think everyone’s work should be as personal to them as possible, but that’s going to be in the work. The artist is irrelevant.

RS What do you mean by ‘soul’ in respect to the artworks?

TM The works that work have power. You make a hundred things and maybe three of them work on that level. Some things have intelligence, like electricity. It knows where to go. You can ground it. I think artworks can have that kind of intelligence because there are moments where someone’s energy has gone through something into another object. If you’re following a painting, you’re following the artist’s thinking with that. So the ones that work have that presence of the artist’s brain.

RS Considering this rejection of identity, do you think this interview is a problem, since it’s exposing people to your personality?

TM Well, we’re trying not to inform them. We’re trying to actually talk about ideas.

RS But your personality is revealed in your words…

TM No, you’re quite right. We have to choose to talk about things around the work, right? Because we’re never going to give someone an experience of the artwork through an interview. But this is my position and I’m putting that forward. You are putting a philosophy into the work. Artwork is philosophy.

Making My Own Porn

RS Taken all together, your body of work feels like a unified world, almost a mythology. Is that how you see it?

TM I’m happy that that’s how you see it. I guess I’ve painted now for about 15 years, and when I started painting I became really aware that I couldn’t express my full position within one or two or three paintings. And so I trusted that, if I continue working, a perspective would become clarified. If I’m fighting for something, I don’t have to show all that fight in one painting. But I don’t go into a world in my head. My internal transgressions would always fight against any kind of a programmatic process like that.

In terms of mythology, they seem more like fables, right? I’m reading this book called Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, from the 1700s. It is by Pu Songling, who wanted to be a literary master, but he was rejected. So he had to just teach Mandarin in local schools. And then he wrote these amazing ghost stories.

RS You just described an artist as a way to describe their work…

TM Did I? [laughs]

RS You have a pretty distinct style, but if you fight against a programmatic process, do you also try to push against it?

TM I mean, one’s style can depict their attitude obviously towards the thing. So style is attitude. My problem with style is that style can become familiar. If you can recognise someone’s style, then you might not look at the thing anymore. I’m very interested in communication through the paintings. So I do fight against my style sometimes because I want to surprise the viewer into looking again and not recognising my work in some kind of a shorthand. Or even recognising myself. Forget the viewer! I mean, I guess I’m retracting what I said before. I am the viewer of my work, in moments. And I’m not interested in having a shorthand experience.

RS Are you saying that all your paintings are based on a communication of ideas?

TM Yes. I think all painting is conceptual. Painting is thinking and painting is a language. In a way, the more you paint, the harder it becomes to paint. You can say painters are like very, very addicted heroin addicts. You want to have an experience every time you’re making something. Every time, I’m looking for a high. But that is antithetical to having an idea. And it might lead to unsuccessful paintings. But at the moment that’s what I’m looking for: pure experiences.

RS When you started making art as a child, were you looking for experiences like this?

TM I think as a child it was purely about communication, I drew a screaming child and gave it to my mother when I was angry once. I had taken art classes in grade school, but the work all seemed not to be mine. Then, one day in eighth grade, I drew Mario from Super Mario Bros. And I made it look like Mario. And that was a revelation: you can make something look like something! And that was my first turn-on. And then I was in love with someone and I just started drawing naked Roman statues from books. I couldn’t buy porn so I just made my own. So then there was that turn-on: they’re naked, and I’m going to put them next to each other. And I think that was it, basically. That just got me hooked: sublimating sexual desires was how I started drawing.

RS Transgression.

TM Yeah, and lack of porn accessibility before the internet.

RS A lot of boys draw violent things, which is probably a similar impulse. If you can’t act something out in life, do it in art.

TM Exactly. Guns or tanks or something. That’s what they were doing in Iran, too. That’s what’s so brilliant about it. For children and adults. I’m mostly interested in works that have that component. Art that excavates from the psyche, not the frontal lobe, not the intellectual, not the speakable, but the unspeakable.

RS Some people would say abstraction is the most obvious example of that.

TM No form has primacy over another form, abstraction, figuration, comic stripes, doodles. It’s only as good as how true it is to the maker. I do think that some forms were transgressive at one time, but not anymore. Right now abstraction is very conservative. You have to work really hard to make a transgressive abstract work. I think it should involve real poo.

Ross Simonini is a writer, artist, musician and dialogist. He is the host of ArtReview’s podcast Subject, Object Verb