The Romanov treasures continued to be crafted, even as their world collapsed around them

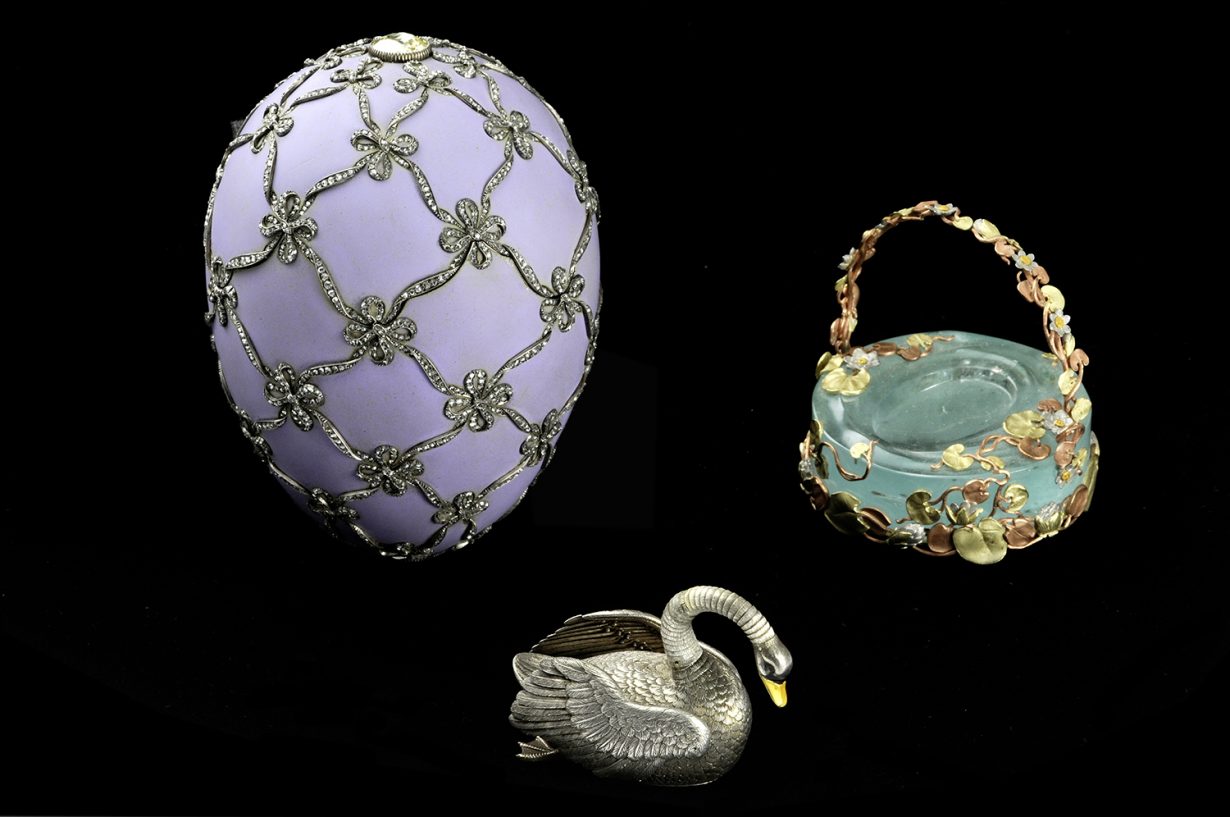

Every Fabergé egg, created for the families of the Russian Tsars Alexander III and his son Nicholas II, contained a surprise – a gold hen with rubies for eyes, a mechanical swan, a jewelled carriage, elaborate clocks, music boxes and so on. In a sense, however, these objects, lavish to the point of gaudiness, were designed for precisely the opposite purpose – to keep surprise, and reality, at bay. The story they tell us is a very different one from that which was intended.

The V&A’s exhibition Fabergé in London: Romance to Revolution is reputedly the largest Fabergé collection in a generation and, though inevitably incomplete, it’s an undeniably impressive haul. It’s revelatory in terms of casting light on the goldsmith Carl Fabergé’s British connection, operating a prestigious London branch from 1903, and the painstaking methods his workshops employed. The allure of the show may lie in its eye-catching glitz but it’s the little stories that really compel – the frost on her window that inspired Fabergé designer Alma Pihl’s ice shard pendant, the diamond snake cigarette case gifted from socialite Alice Keppel to her lover King Edward VII, the Third Imperial Easter Egg that was lost for decades and almost melted down.

A cursory reading of the Easter eggs would suggest a familiar tale of aristocratic hubris. Aside from their curio appeal, the reason they have captivated the collective imagination for over a century is because of their association with a romanticised lost age (the crown jewels of other, surviving, European royal houses do not possess the same degree of chimeric allure). Yet these specific objects, both those on display here and others in private collections or missing entirely, tell us something much more universal, and troubling perhaps, about intention and fate.

The backdrop for the Fabergé egg tradition was not fortuitous. Tsar Alexander II, named The Liberator because he presided over the emancipation of the Russian serfs, had died violently at the hands of a group of young revolutionaries called the People’s Will. His son, and successor, Alexander III was a very different character – a burly autocrat determined to roll back the liberalising reforms of his father. It’s debatable whether this slowed or accelerated the decline of the Romanov dynasty (when the secret police foiled an attempt on the monarch’s life, the resulting hanging of one of the conspirators Aleksandr Ilyich Ulyanov only served to further stoke the wrath of his younger brother – Vladimir, or Lenin as he came to be known).

Alexander was both a reactionary and a romantic, commissioning Fabergé to create an easter egg for his tsarina every year, beginning with the charming minimalist Hen Egg (1885), on display here, and increasing in extravagance and detail. They were demonstrations of imperial might but also detachment, insularity and vulnerability, continuing to be produced right through the catastrophic radicalising Russian famine of 1891. The tsar would die young, possibly from lingering injuries sustained saving his family during a train crash, passing on power to his son Nicholas II, sentimental and inconstant, who took further refuge in a world of magical thinking and squandered every opportunity for change. The eggs continued to be crafted, even as their world collapsed around them.

As much as it is tempting to approach these items of obscene wealth with a degree of moralism, the stories they tell contain unexpected pathos. They were initially intended as gifts of love, from the tsars to their wives and from Nicholas to his grieving mother. They celebrate the birth of their children; a family emerging, sometimes mechanically, in the form of miniature portraits, a family that we know now are doomed. In other cases, they seek to ease the homesickness of the tsarina – a rosebud to remind her of the distant gardens of her youth or depictions of palaces she’d lived in. At other times, such as the Twelve Monograms egg (1896), they were designed to allay grief.

There are, however, other messages to be found. An innate callousness comes forth not just in the decadence of the entire tradition, while Russian peasants lived in extreme poverty, but in specific cases such as the Trans–Siberian Railway egg (1900), celebrating an engineering triumph that had exerted a grievous human toll. The Memory of Azov egg (1891) was treated as almost cursed because the journey it celebrates resulted in Nicholas’s near assassination. It seems now a prescient and ignored warning. Similarly, the Pelican egg (1898) features, among its miniature paintings, the Smolny Institute, which would become the base of the Romanov’s Bolshevik nemeses who, after the family’s murder, would sell off many of the Fabergé treasures under the Treasures for Tractors policy (Carl Fabergé, meanwhile, would die a broken man in Swiss exile).

You can see the end coming, even if the Romanovs cannot, through the eggs themselves. It’s evident in the austerity of the final ones; the Steel Military commission (1916) that began to rust; the Red Cross with Triptych (1915) that signifies last-minute compassion and futility; the final wooden Karelian Birch egg (1917), unfinished and undelivered. It’s a story that draws its magnetism from the folk wisdom of the fairy-tale: a foolish aloof regent enthralled by glittering symbols of prestige ignores the world outside, and the material conditions of his kingdom and peoples, until it all comes crashing in. These objects are hypnotically dazzling and therein lies ruin.

Darran Anderson is a London-based Irish writer. He is the author of Imaginary Cities and Inventory.