They are beautiful, but they also seem incredibly far away

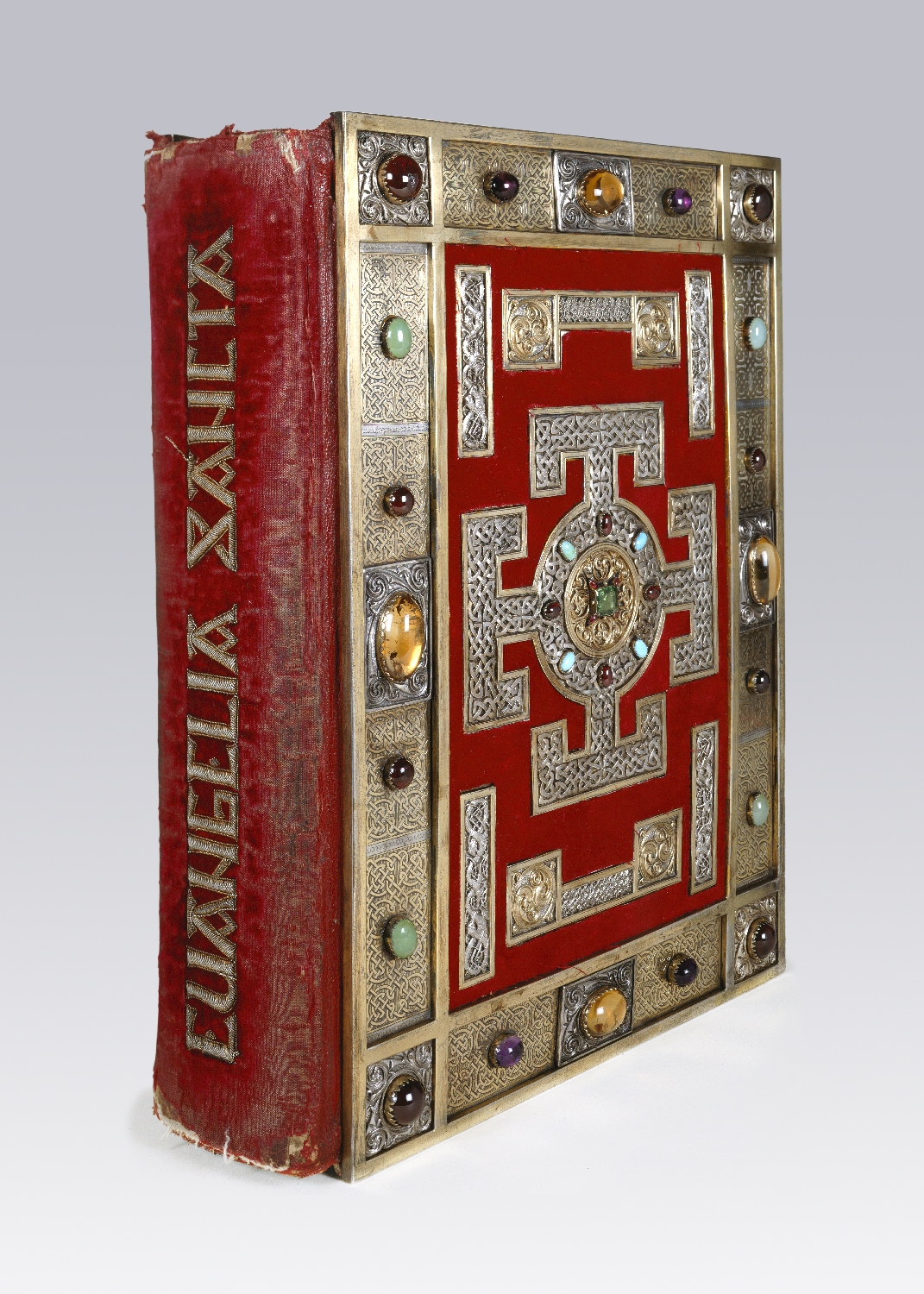

The Anglo-Saxon history of the north-east of England is bound up with that of the monastery of Lindisfarne, located on a tidal island just off the Northumberland coast. It was on Lindisfarne that a group of Irish monks settled after they had been invited by King Oswald of Northumbria, to evangelise his kingdom, which at the time was the most powerful in Britain. It was from this community, founded by Saint Aidan, that the cult around Saint Cuthbert emerged – which would become one of the most significant in Anglo-Saxon and medieval Britain, and led directly to the founding of the city of Durham. And it was on Lindisfarne that Bishop Eadfrith, around the years 715-720, produced a brilliantly illuminated copy of the Gospels, now widely recognised as the most spectacular art-object to survive from the Anglo-Saxon world.

Anglo-Saxon history is difficult: when you live somewhere like the north-east, it can feel like it’s worth knowing about these old saints, alongside people like the Venerable Bede (who was based nearby, at Monkwearmouth-Jarrow, and whose writings did much to spread word of their deeds). This, after all, is your heritage – back from when places that are now English Heritage spots only accessible by car, or stops on the Tyne & Wear Metro where the nearest place to get food is a Greggs on an industrial estate, were among the most important centres of art and learning in the Christian world. But equally, for that very reason, this history is almost intangibly distant: what these various monks did has honestly very little relevance to what the north-east is like today.

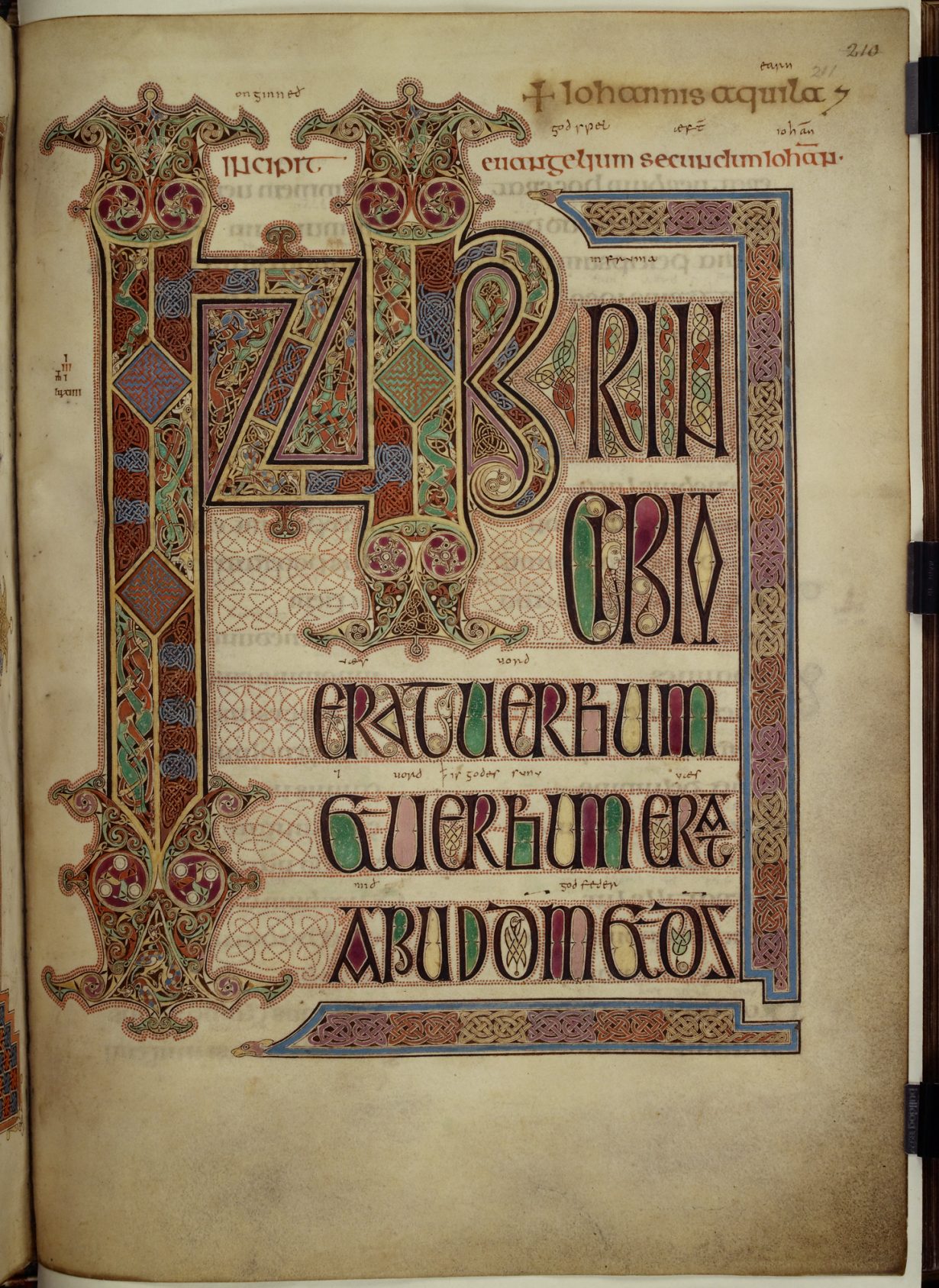

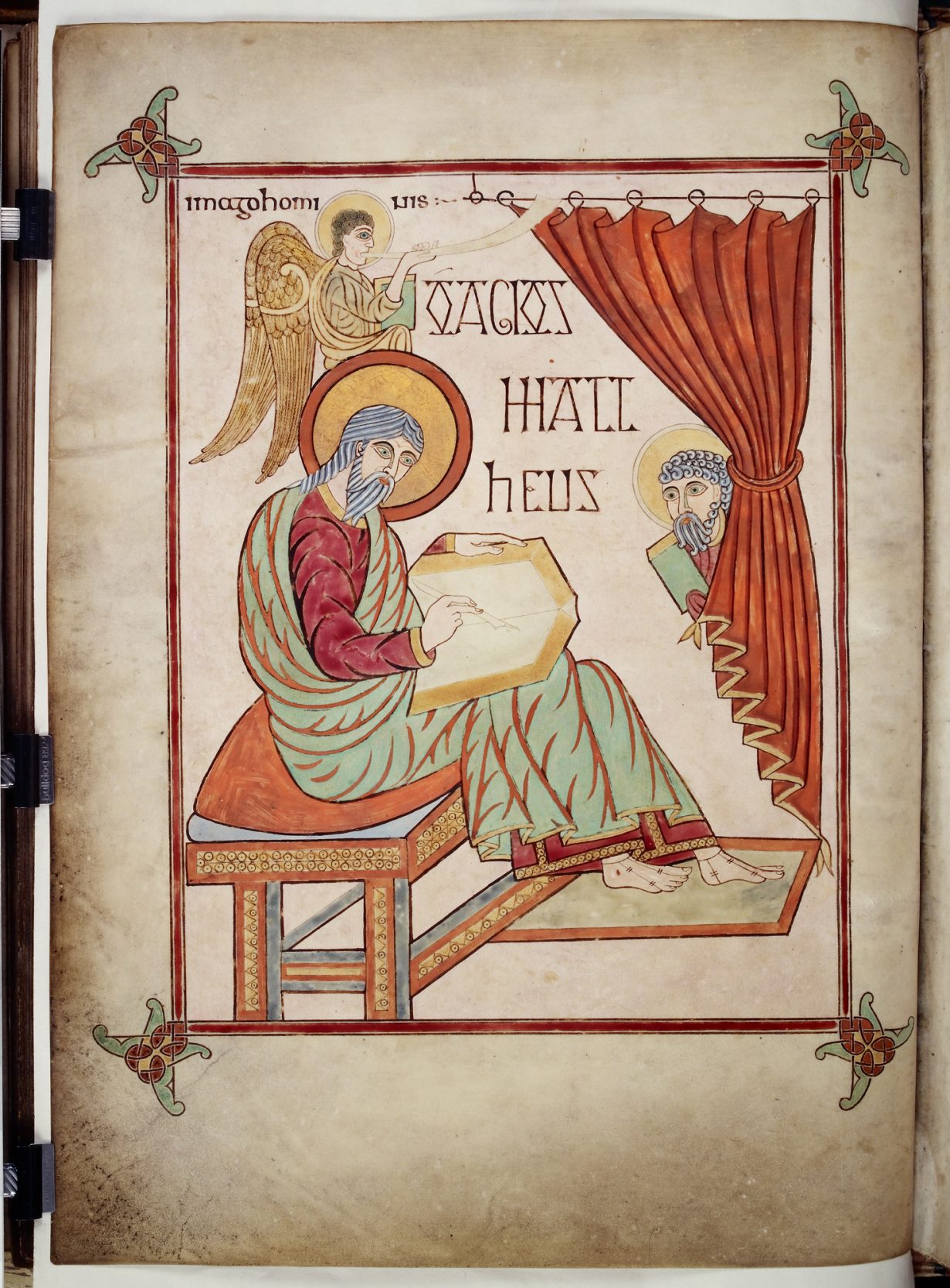

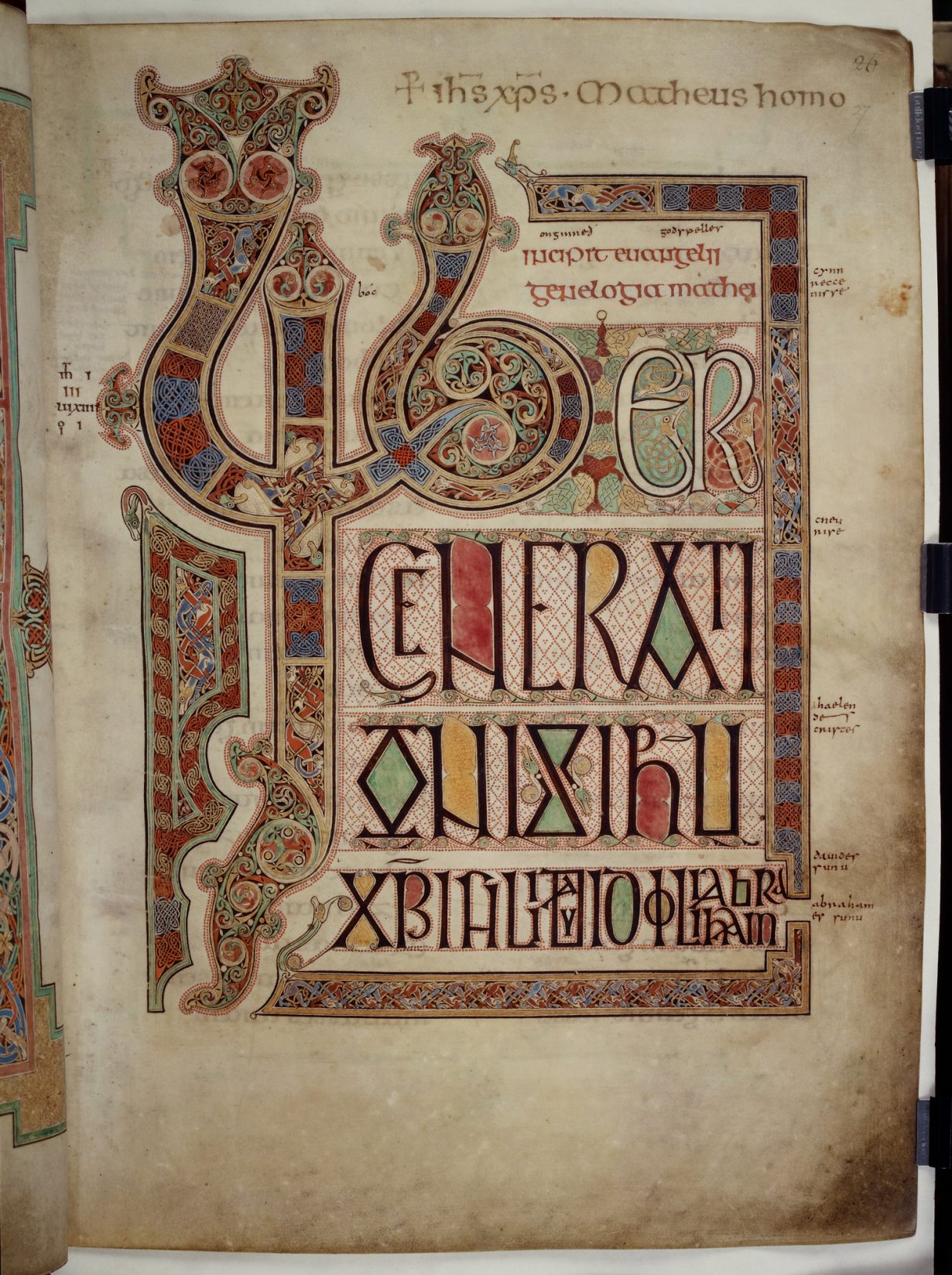

That said, the Lindisfarne Gospels are still, obviously, very beautiful – anyone can see that. Essentially, they are a brilliant example of ‘Insular’, or ‘Hiberno-Saxon’ art, from a time when artists in Britain and Ireland largely produced work in a common style distinct from that of the rest of Europe – although the Gospels do also incorporate elements of Germanic and Byzantine styles. From a time when producing a book was an immensely painstaking process that could take years, works like the Lindisfarne Gospels turned the practice of copying letters onto sheets of vellum into an act of worship: their brilliant incipit pages, for instance (opening each of the Gospels of Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John), turn the letters themselves into a dizzying abstraction, divided into rectangles, swimming with coloured patterns that on closer inspection turn out to be comprised of animals or birds. At times they almost resemble Islamic art: the immense complexity, and immense harmony, of their patterns a way of glorifying the creation of God.

But equally: for all the Lindisfarne Gospels are a visible, comprehensible part of north-east heritage, they do not literally belong to the north-east. Normally, they’re kept at the British Library in London, which a lot of people don’t like (there has been a campaign to relocate them). So it’s exciting, for north-east heads at any rate, that the Laing Gallery in central Newcastle is exhibiting them right in the middle of the north-east’s capital, from now until the start of December. The exhibition arranged around the Gospels includes a film which tells the story of the abbey on Lindisfarne, a number of other similarly old (less accomplished, but still beautiful) books, and works by more recent artists which explore spiritual themes – the most striking are pieces by Mariele Neudecker, Markéta Luskačová, and Khadija Saye.

Neudecker’s mutilated Bible evidences a very different to attitude towards religious texts since the invention of the printing press; Luskačová’s photographs document religion and resistance in the former Eastern bloc; while Saye’s haunting self-portraits depict the artist, who tragically died at Grenfell, obscuring her face with a series of West African religious objects. Saye and Neudecker’s works, in particular, offer a powerful thematic complement and contrast to the Gospels themselves. There is also a new film by Jeremy Deller, produced specifically to celebrate the coming of the Gospels to Newcastle.

Deller’s film seems to have been designed to capture some of the excitement people might feel at the return of the Gospels to their native region. Starting at the British Library, we see the Gospels being lifted from their usual cabinet by a curator, before they are very cautiously placed into a specially-designed box. They are then put in a sort of storage facility, alongside the smaller Saint Cuthbert Gospel (which isn’t usually on display). After the books chat to each other in Old English for a bit, a sort of New Order-y sounding tune starts playing, and the Gospels are whisked off on a ’90s computer animation-looking journey through space and time, whereupon they land in the Dog & Parrot pub next to Newcastle railway station and are greeted by some zoomers who look like they’re advertising the joys of sharing a particular brand of crisps with your friends. The zoomers dance with the Gospels through the streets of Newcastle – before depositing them, joyfully, in the Laing.

I kind of get what the film is trying to do, but the feeling it is attempting to summon up feels rather forced. It reminded me a bit of Phil Collins’s magnificent Ceremony (2017), where an Engels statue is seen being transported to Manchester from east Ukraine. There, the sense of wonder and community at the arrival of the statue felt real, if for no other reason than that the statue had previously been considered junk: it was something deemed substantial enough to touch, ephemeral enough for people to assign their own meaning to.

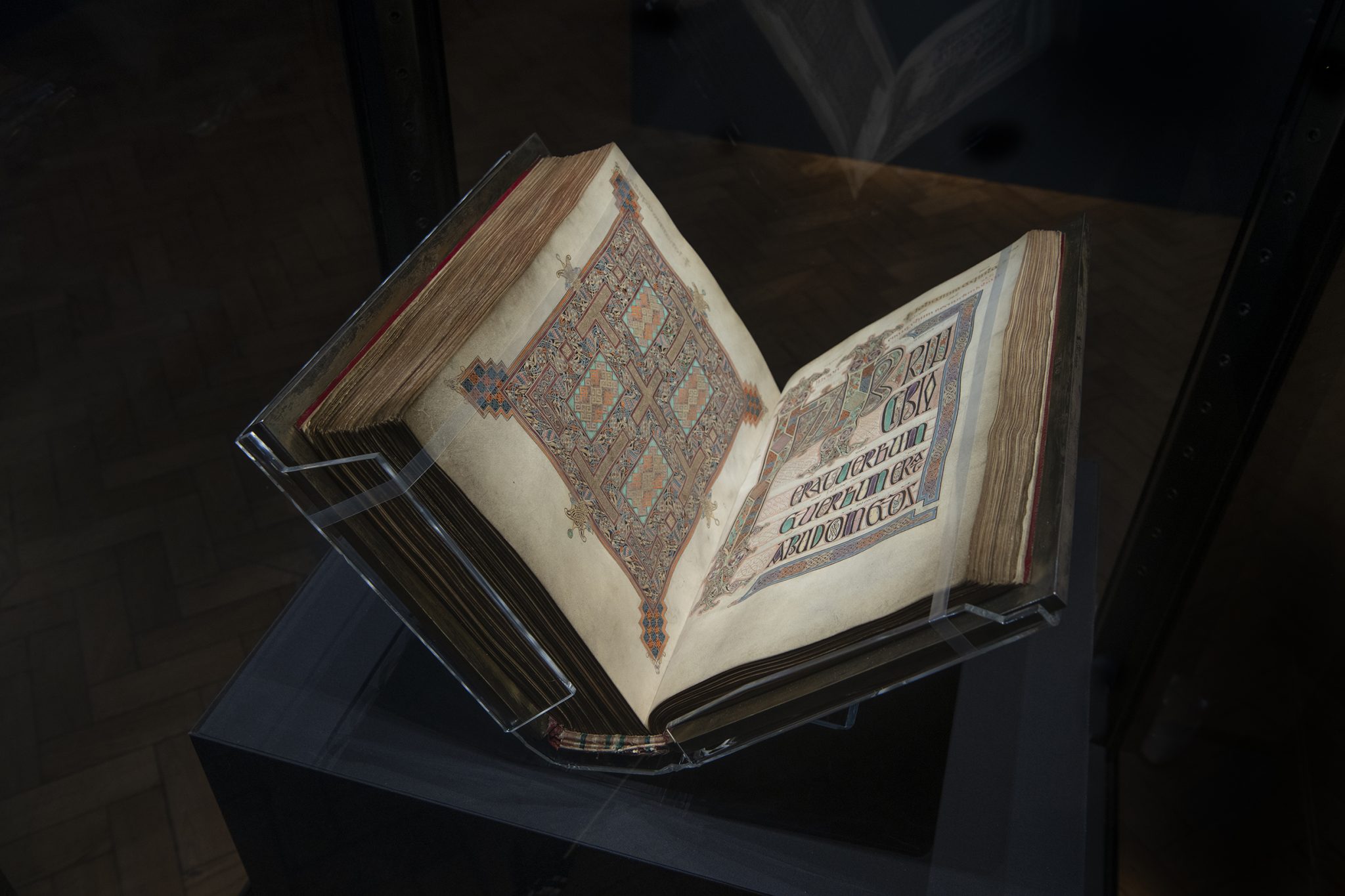

But this is not what the Lindisfarne Gospels are – nor what most of the other stuff accompanying them is, in the exhibition. What struck me most, looking at the dates involved here (eighth century, ninth century) is how all of this stuff is just so incredibly old. There is one book on display here, an Irish ‘pocket gospel’, which was originally transcribed around the time of the Lindisfarne Gospels, but then has later embellishments: extra pictures, which were added when it was rebound sometime in the sixteenth century. The clear implication being: that this is a religious text which functioned, as an active part of religious life in some distant part of rural Ireland, for over 800 years (conversely, there is a fragment of a Celtic cross on display here which was discovered in the Victorian period being used as a tool for squeezing water out of laundry in Yarm). Distances in time like this can barely be thought about: they are almost impossible to get your head around. The Gospels themselves form the centre of the exhibition – but they almost seem too small, smaller than they ought to be, and of course there are only a couple of pages actually on display. They are beautiful, but they also seem incredibly far away.

What these objects have is ‘aura’, as Walter Benjamin described it in essays like ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (1935): they are cult objects, religious objects that are unique, authentic; that possess some quality which could never be replicated. They are the real thing: the Lindisfarne Gospels, exhibited here in the Laing, really are the real book transcribed and illuminated by Eadfrith, on an island off the Northumberland coast in the 700s AD. And so they possess something which eludes us: we could never replicate what makes the Gospels so special through mechanical means.

You don’t actually see a lot of the Gospels, at this exhibition which is dedicated to them. But equally, you never could. The Gospels were designed to be beautiful, but they are beautiful religious texts, from an era where almost everyone could not read. Their beauty honours God, and not the public. It is not there for you. The beauty of the Lindisfarne Gospels will always sort-of escape us: just like the past they have emerged from, it will always feel far away.