A new survey at Palazzo Grassi, Venice positions Mehretu amid a wider web of artists, musicians and theorists – including Paul Pfeiffer, Tacita Dean, Fred Moten, Pharaoh Sanders and Huma Bhabha

The sound of Pharoah Sanders’s improvisations on tenor saxophone hit on first entry into Julie Mehretu’s survey exhibition, Ensemble at Palazzo Grassi. Promises (2021), an album born of a collaboration between Sanders, electronic producer Floating Points and the London Symphony Orchestra, forms the audible dimension of the film Promises Through Congress, by Trevor Tweeten. Sanders’s improvisation moves against and with a trill that repeats every nine seconds while the camera slowly retracts from the canvas of Mehretu’s painting Congress (2003) for the full 46-minute duration of the composition. In the first frames, intersecting black lines resemble notes on a stave, then as more of the painting enters the camera’s scope, shards and fragments reveal an ever-more complex enmeshment.

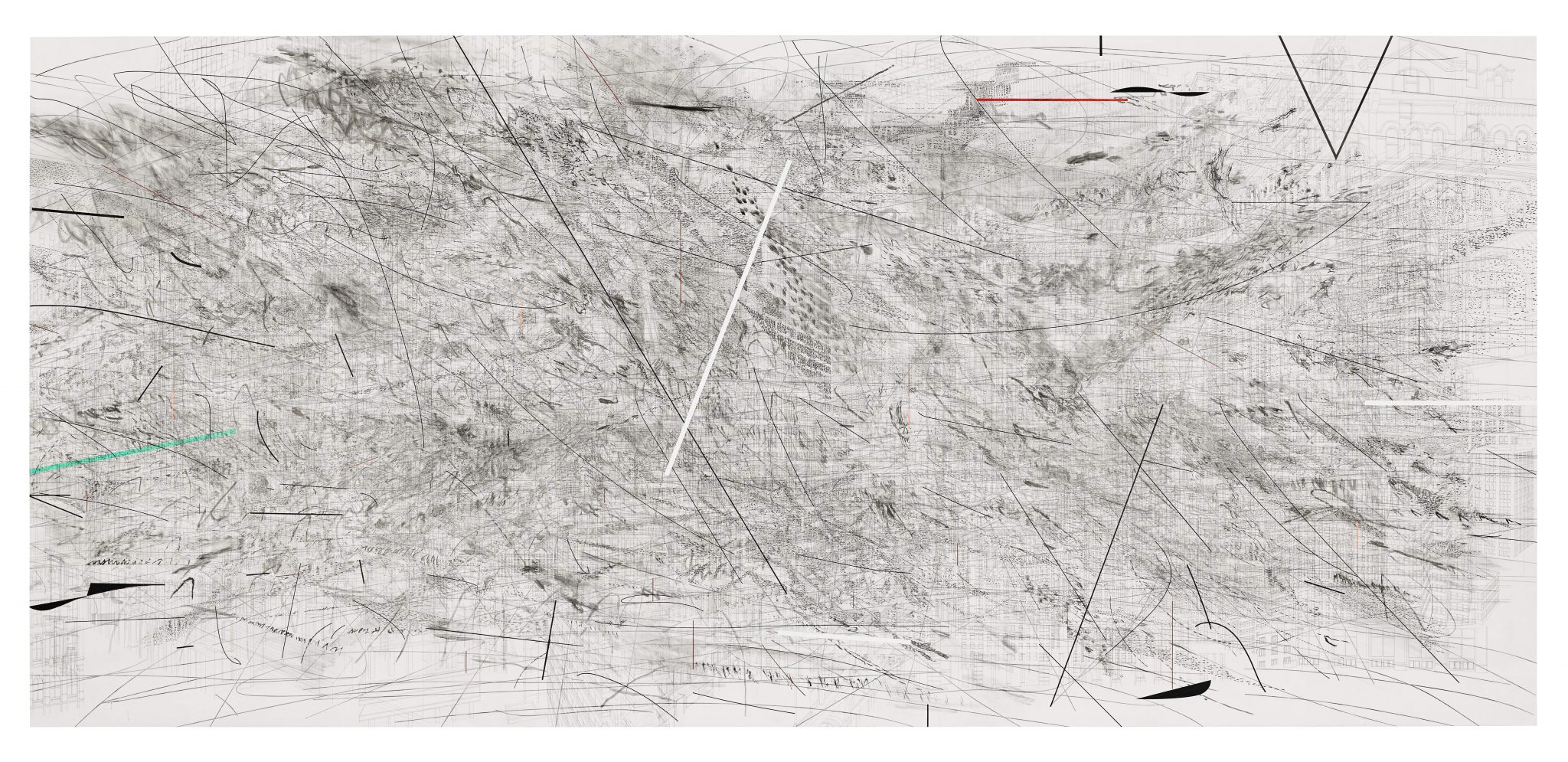

The structure of Promises echoes Mehretu’s technique from 2001 to 2016, and some of her most impressive works from that period are present across two floors of Palazzo Grassi. Like Sanders’s improvisation which runs, against, around, alongside and through the ritornello, Mehretu layers her freehand ink marks over the smooth, regular geometry of architectural drawings after they are ‘sealed’ with a clear layer of acrylic. The drawings are not a straightforward re-presentation (or reenactment) of buildings. In Invisible Line (collective) (2010–11), Mehretu combines New York’s past, present and unbuilt structures with pedestrian and aerial views of the city. Up close: freehand marks amass, entangle and merge with the architectural schematics; black dashes suture window frames from one edge to another, the mark-making working as much with the schematic as Mehretu’s precise black swoops move despite it.

The painting is installed on a long wall on the first floor, overlooking the Palazzo Grassi’s entrance hall and lit partially by diffused natural light. Opposite, against the balustrade is a bench where the painting cannot be viewed straight-on without a hulking sculpture by Huma Bhabha (New Human, 2023) encroaching on one’s peripheral vision. The magnitude of Invisible Line (collective) and the distance of the bench also makes it difficult to take the painting in all at once, requiring the viewer to move, at least from the neck up, to begin to experience it. The curation enhances Mehretu’s challenge to what the philosopher Michel de Certeau, writing about the view from the heights of the former World Trade Center, describes as the ‘voluptuous pleasure of the Solar Eye’, the fantasy of ‘seeing the whole’. For de Certeau, this vantage point obliterates the body: ‘The exaltation of a scopic and gnostic drive: the fiction of knowledge is related to this lust to be a viewpoint and nothing more.’ We are instead forced into spatial negotiations with Bhabha’s New Human, a captivating figure hewn of cork and MDF with circles at the eyes and nipples, a line marking the genitals, and a partial skeleton marked on its surface in bright white acrylic.

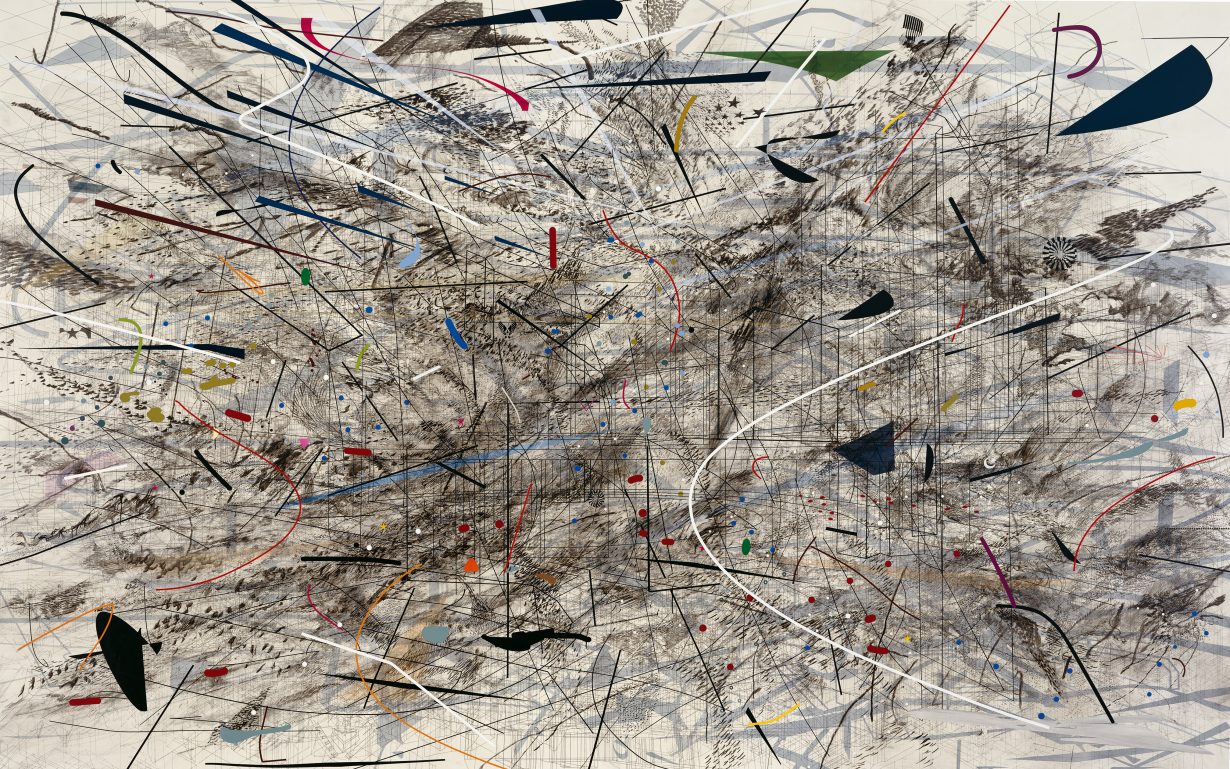

If a line demarcates, instructs us that one object or moment has passed and another has begun, then Mehretu’s mark-making complicates that function. In Black City (2007), Mehretu slants and morphs castle and fortification walls until they are indistinguishable from clusters and waves that move across the canvas in every direction. The kinesis of her mark-making overtakes the architectural schematics that in other paintings stand out or hold their own. Black dots, marks, smudges, swoops and colourful clean shapes reminiscent of Suprematism move even at the edges of Black City. Where the architectural form reappears in the top left corner, Mehretu paints a tick. If architecture is an act of demarcation on a grand scale, an exercise of the power to organise our lives, does Mehretu’s gesture warn that this hand will either approve the exercise of power or obliterate it? Or maybe the artist is just pleased with her work.

The architecture of our cities is decided for us, often subjugating the needs of people to the whims of financial markets. Even when Mehretu’s schematics recombine and remix existing buildings, producing plans for fictive cities, they still existed as a discrete layer, which had also become a recognisable marker of a Mehretu artwork. The paintings after 2016 remove this layer. In Hineni (E. 3:4) (2018), Mehretu achieved the painting’s smouldering orange tones by digitally manipulating a photograph of the 2017 Northern California wildfires and then airbrushing the resulting blurred haze of colour onto her canvas. The process makes the source image unrecognisable and the first layer indistinguishable from subsequent applications of ink and acrylic. In works since, as the title Everywhen (2021–2023) makes explicit, obscuring the layers removes temporal and geographical markers and renders dissection as a tool for encountering the paintings redundant. By making the layers legible in her earlier work, Mehretu’s paintings offered the kind of euphoria that we derive from looking at photographs of the galaxy – that even the unknowable can nonetheless be captured by the camera lens and contained by the human eye. They also made one operation of domination – spatialisation, urban planning, the schematics of financial capitals – visible and available for critique. The artist’s shift towards haze and blur resists the urge to ‘see the whole’ and to possess and understand by seeing.

From here the exhibition elaborates its challenge to the notion of the artist as a self-sufficient entity. Paul Pfeiffer’s sculptures of Justin Bieber, rendered in the posture of a crucified Jesus and dismembered, appear alongside Mehretu’s paintings, aligning the shock and humour of Pfeiffer’s human-scale works with Mehretu’s broader recognition, of the violence of atomization as a mode of possession. A piano composition by Jason Moran, created while Mehretu painted beside him, connects the first floor to the second and Jessica Rankin’s threaded canvases, which predate Mehretu’s TRANSpaintings (2023), large semi-translucent works on a monofilament polyester mesh that allow the light to pass through. These are also a collaboration. Nairy Baghramian’s frames stand the paintings throughout the middle of the gallery so that visitors must walk among them. Their positioning in the room privileges their relationships with each other.

These collaborations and conversations form the climax of Ensemble, which feels liveliest on the second floor once visitors have seen enough of the other artist’s works to recognise the resonances between them. Mehretu’s final work in the show, Desire was our breastplate (2022-23), derives from a line in Intimacy, a film by the poet Robin Coste Lewis which plays on loop in a nearby darkened room. Two smaller works by Huma Bhabha are here, too, echoing her installation on the floor below – and the gesture of the sprayed nipples and genitals from New Human appears in Mehretu’s about the space of half an hour (2019–2020). A single gesture in the work of one artist is amplified in the work of another. In her exhibition essay, Mehretu writes of ‘countless hours’ spent pondering the ‘third eye’ in David Hammons’s Untitled (1976), a body print in pigment on paper that ‘lives’ in Mehretu’s home. And indeed then, eyes are dotted across Oneironaut 1 and 2 (2021–22), Panoptes (2022), and most strikingly in Atlas (2016–21), where a cluster of open black eyes loom at the top of the huge canvas – a symbol of non-cognitive knowledge, a ‘third eye’, or an omnipresent surveillance that would attempt to map the whole globe.

A quotation from an interview with the theorist Fred Moten opens Mehretu’s essay in the exhibition publication. There, Moten attempts to get free of ‘possessive individuality’, the notion that ideas, thought, gestures belong to or derive from a discrete and bounded individual. So he eschews referring to ‘Édouard Glissant’s work’, for example, and opts instead for ‘that body of work under the name of Édouard Glissant’. The way Ensemble’s second floor affords as much space to apparently unintentional influence as it does intentional collaboration, points to the joy and possibility on the other side of such possessive individualism. In this part of the exhibition, at last, Mehretu is one in the ensemble.

Derica Shields is a writer, researcher and cultural worker from London. She is completing ‘Bad Practice’, a book about failure, for Book Works.