The prolific Indonesian director’s work has been censored, cancelled and erased. What can we learn from that which remains?

In recent years, the secret history of what took place in Indonesia during the anti-communist purges of 1965–66 – and its wider ramifications – has come to light through a range of important investigations. Joshua Oppenheimer’s extraordinary 2012 documentary The Act of Killing, for example, deployed an extreme closeup approach centred on reenactments of torture and murder by the perpetrators. Then there’s Vincent Bevins’s The Jakarta Method, a 2020 book that hails Oppenheimer’s film for having ‘smashed open the black box surrounding 1965 in Indonesia’, but which enlists a different technique. To tell the story of these events, and the global extermination network they engendered, Bevins’s political history traces the wider geopolitical contours of the Cold War – not least, the CIA’s deep involvement in the purges.

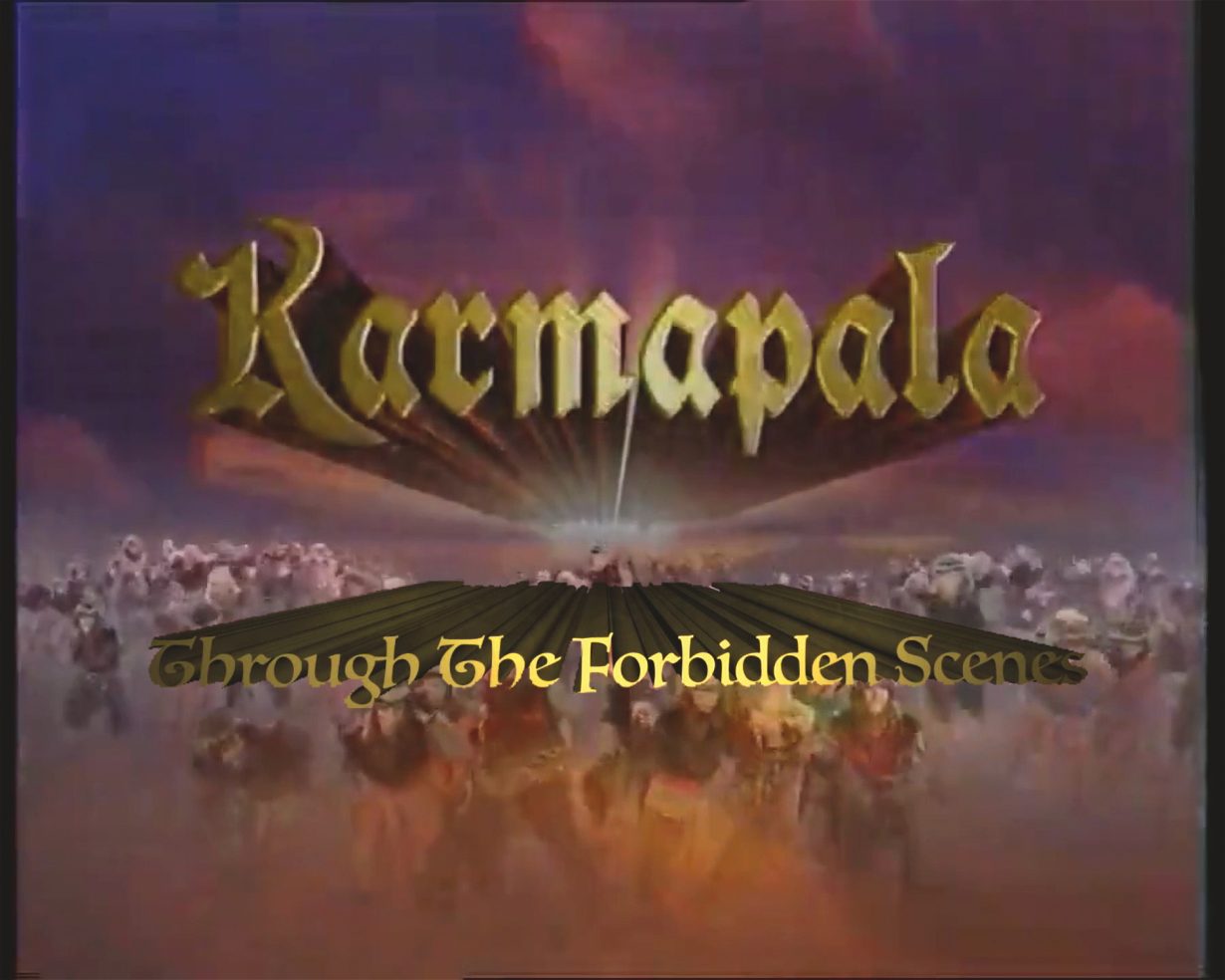

It was with these indelible frames of reference in mind that I recently caught a screening in Bangkok of Karmapala Through the Forbidden Scenes (2023), a short film that its cocreator, artist-curator George Clark, prefaced in an introductory speech with the claim that it “offers a different way to think about the history and representation of the Cold War”. What unfolds in this 20-minute short certainly lives up to that billing: comprising repurposed footage appropriated from an early-2000s ‘sinetron’ (Indonesian TV miniseries) called Karmapala, it features a cast of mythic beings who bound balletically through skies, gallantly wage battle in verdant Balinese forests, brandish gem-studded swords and generally make mischief. In the opening scene, a princess is approached by a thirsty old man, who transforms with a puff of smoke into a king, then whisks her up into the clouds to rape her. The princess, ashamed of her defilement by the king, then commits ritual suicide by leaping into a fire. In subsequent scenes, this turn of events compels her valiant brother, Wayan, to revolt and seek a new vision for society.

In Hinduism, the term karma phala refers to the ‘fruits of one’s actions’, and it is this connection of cause and effect (and its implications for our future lives) upon which this short hinges: it is an attempt to bring to fruition a film that a now-deceased Indonesian director never got to make.

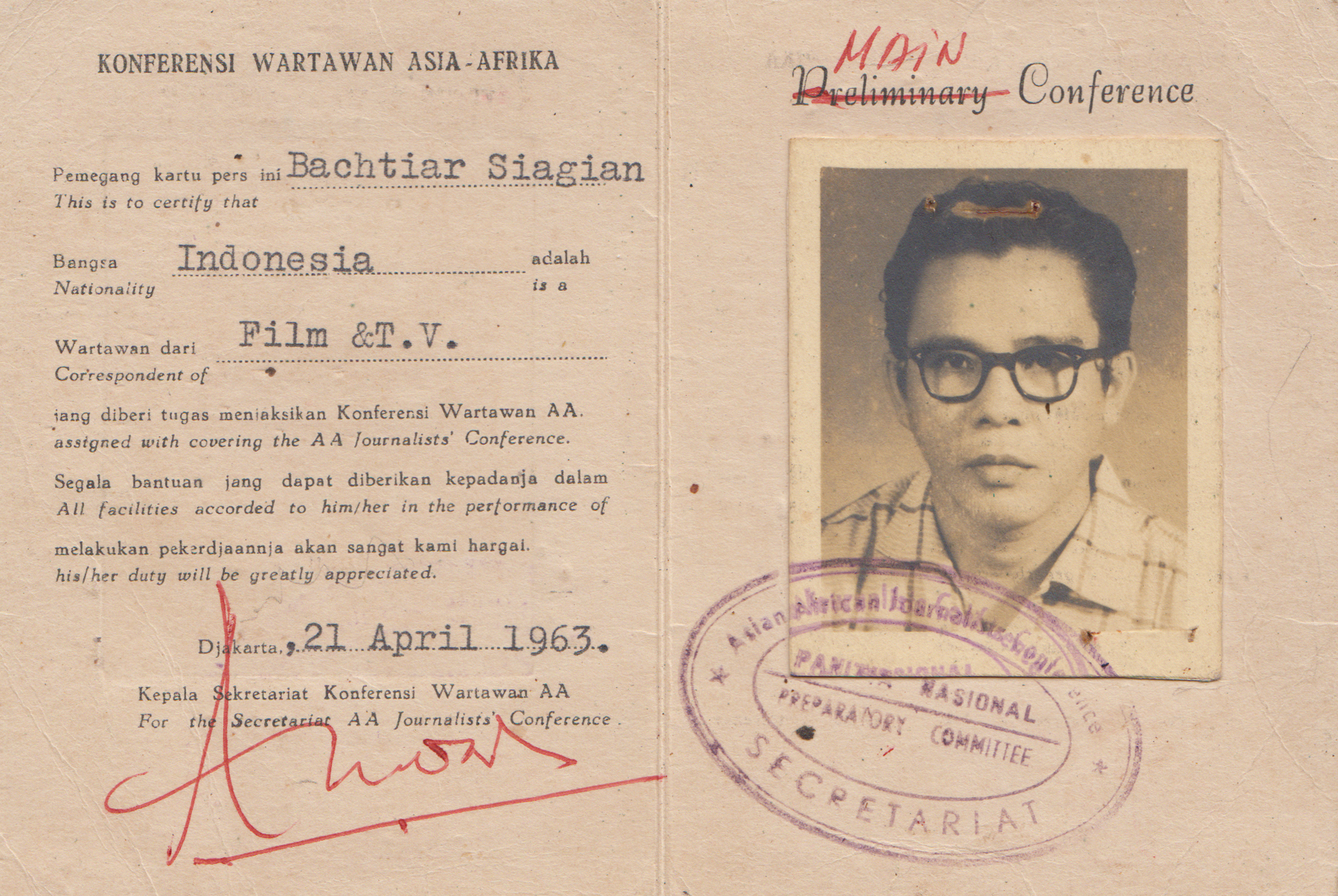

“In 1962, Bachtiar Siagian submitted to the Balinese Historical Council the concept for a film to be called Karmapala,” the prologue states. Backed by the governor of Bali and President Sukarno, this film about the making of a revolutionary was set to be his most ambitious to date. But the US-backed military overthrow of Sukarno’s government in September 1965 put a halt to it: Bachtiar spent the next 12 years in jail (the stigma of which meant his directing career was over upon his eventual release) as part of a sweeping crackdown on leftists and suspected communists, so the film was unrealised – until a version of sorts came out around the time of his death, in March 2002. “In the year of Bachtiar’s death, Karmapala was reborn as a sinetron TV series,” the prologue continues. “While bearing the same name, it is far from his revolutionary ambitions.” The outcome of a collaboration between Clark and Bachtiar’s daughter, artist-curator Bunga Siagian, Karmapala Through the Forbidden Scenes uses the ten hours of this exuberant show as source material for an unauthorised revival of Bachtiar’s true ambitions.

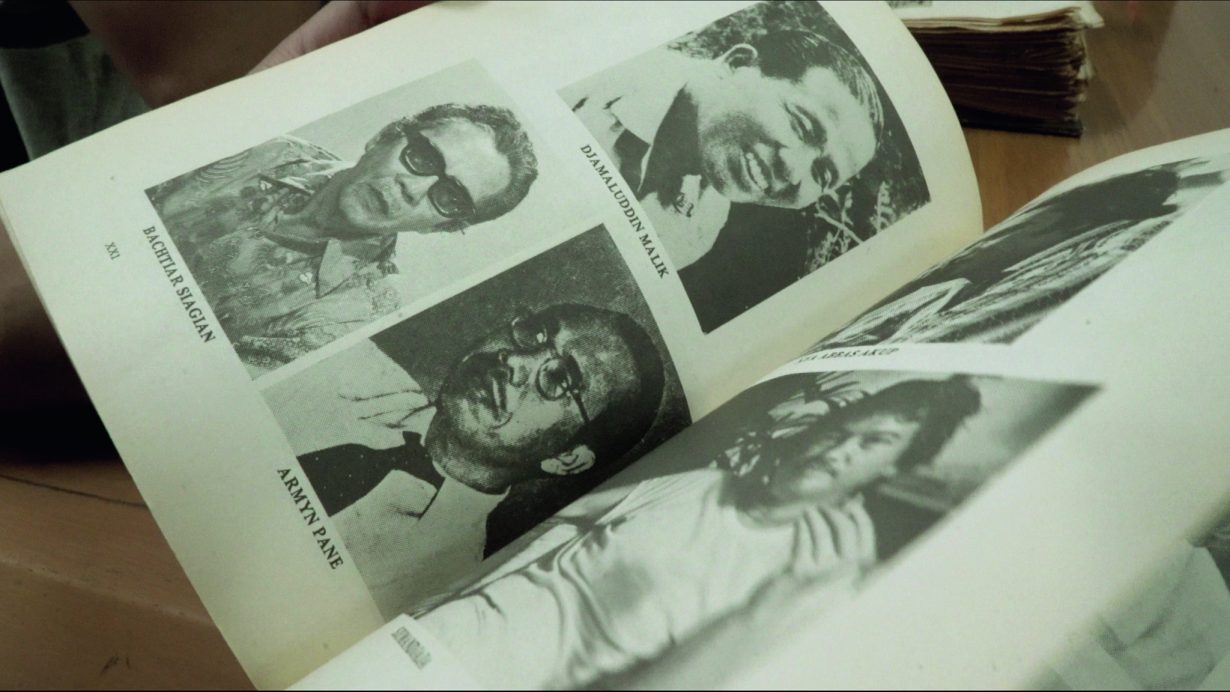

Inadvertently, this speculative work (originally conceived for the ‘Film Undone – Elements of a Latent Cinema’ gathering in Berlin in 2023) now looks like an elaborate preamble – other notable gaps in Bachtiar’s legacy have subsequently been filled. Focused soberly on the events of his life is Hafiz Rancajale’s new documentary Bachtiar (2025), which follows Bunga and her brother as they struggle to bridge the biographical lacunae resulting from their father’s captivity and subsequent pariah status during the 32-year-long New Order dictatorship led by President Suharto. They head to the farmlands of Binjai, North Sumatra, where their father was born in 1923; they sift through his heavily annotated scripts, diaries and letters; they meet with his old friends and acquaintances. And by seeking out the scattered traces, documents and facts relating to Bachtiar’s films, they begin to challenge the warped official history resulting from the almost complete loss and destruction of them.

Permeating this documentary is the suggestion that Bachtiar’s imprisonment without trial was the result of a perverse misreading, or oversimplification, of his true sympathies. (He was a member of LEKRA, a leftwing cultural and social movement closely associated with the Communist Party of Indonesia, we learn, but he claims not to have been wedded to its doctrine of social realism: “What was needed was not socialist realism”, he says in a rare audio recording, “but a romantic realism that was anti-imperialist.”) But also preoccupying its makers is the question of where he belongs in the annals of Indonesian film history. One of the most prolific film directors of his generation, Bachtiar wrote and directed 13 feature films between 1955 and 1965, as well as numerous documentaries. But, with nearly all of them missing, his legacy has been overshadowed by the likes of Usmar Ismail, a more aristocratic and staunchly individualist director who worked contemporaneously but sat at the right of the ideological divide, and so did not experience prison, nor the purging of his films (prints of which are preserved in Sinematek Indonesia, the country’s film archive).

According to Krishna Sen, a journalist who interviewed Bachtiar during the early 1980s, this is a travesty. ‘Although Bachtiar had less than a decade of involvement in cinema, his work seems to have taken a direction that was different from that of any other prominent filmmaker of his generation,’ she writes in her 1994 book Indonesian Cinema: Framing the New Order. The suppression of his films – which were produced at a time when postindependence Indonesia was still in a phase of becoming – marks, for her, ‘the end of a form of cultural critique’ that yielded atypical protagonists (such as an evicted slum-dweller, a prostitute, a poverty-stricken horse-keeper) and aligned with the ‘growth of a forceful egalitarianism’ that wasn’t coming from ‘any utopian socialist or developmentalist vantage point’.

Sen’s couching of her assertions with ‘seems’ is important: she had not seen any of Bachtiar’s films when she wrote her book, so was forced to rely on scripts, synopses and interviews. This predicament – and the educated guesswork it forces – is echoed in the documentary, in which an independent film collector asks: “How can we consider… Bachtiar Siagian as the father of national cinema if we cannot trace his films?”

Tracing his films is something that Bunga and others are actively trying to do. Towards the end of his documentary, director Rancajale announces in a wistful voiceover that a lost Bachtiar film was recently found at the Russian Film Archive, Gosfilmfond. Consequently, Turang (1958) – a neorealist film about rebel soldiers fighting the Dutch colonial army during the Indonesian National Revolution of 1945–49, shot in the villages and tilled fields of North Sumatra’s Karo people – is also now touring the international film-festival circuit. With its scenes of guerrillas and villagers joining forces, and romanticised theme of comradeship and self-sacrifice, one can see why it apparently played well at the 1958 Afro-Asian Film Festival in Tashkent, Uzbekistan (a festival forged in the ‘Bandung Spirit’, the set of anti-colonial, liberatory principles that emerged from the 1955 Asian-African Conference in Bandung, Indonesia). In tone and subject matter, it contrasts starkly with the only other surviving Bachtiar film, Violetta (1962), which is about a young girl and her overprotective mother.

Another strategy involves trying to work round the gaps using more creative methods – as Bunga and Clark do in Karmapala Through the Forbidden Scenes. This they did by engaging, firstly, with Krishna Sen’s written account of Karmapala’s plot (as relayed to her by Bachtiar) and, secondly, by borrowing the methodology of cultural activist Akbar Yumni. For his 2023 performance Watching Daerah Hilang, Yumni reenacted in front of a Berlin audience six scenes censored from a lost Bachtiar movie (Daerah Hilang, 1956) – scenes partially described, and so preserved, in an article he came across by a film critic. “So you can’t see the film, but you can read about the things the censors didn’t like,” explained Clark, speaking at the recent 7th Bangkok Experimental Film Festival. “We found the idea of a film becoming visible through the things that are prohibited very interesting.”

Resorting to this desperate measure, using it to imagine ‘possible forbidden scenes’ from Bachtiar’s Karmapala – in which the Balinese villager Wayan’s awareness of social injustice is raised – struck them as a fun, provocative way to honour Indonesia’s leftist cinematic legacy and its skirmishes with censorship. And a way of doing so while avoiding the ‘funerary air’ that pervades many, if not most, attempts to memorialise the absences, or unearth the secret histories, of the Cold War. “If we only deal with absence through memorial, the funeral procession will be so long,” said Clark, who went on to explain how Bunga and he, after imagining these forbidden scenes, carved them out of the ten hours of the TV show via a process of reordering and reediting. “All of the dialogue is translated as it is, apart from where we add a word on top of the subtitle,” he said. “But apart from that, we could find the story in there.”

Dicing and splicing this series – a national allegory dressed up as a tale of a rivalry over a sacred artefact – is also an ironic gesture, as it is itself an example of the enduring cultural hegemony of Suharto’s New Order regime, which lasted until the late 1990s. “Its image has persisted because it destroyed so much of any images that existed before,” he said. “And so it persists in the imagination. This TV show is a product of that.” Viewed through this pop-culture lens, Bunga and Clark’s intervention seems to echo, or belatedly bring into being, the dialectic of personal tragedy and emancipation central to Bachtiar’s unrealised version of Karmapala, wherein Wayan’s conscientisation leads him, as Sen writes, ‘from acceptance of established values to rebelling against them’.

More mediated conversation with scant source material than big discovery, Karmapala Through the Forbidden Scenes might not settle the still open question of Bachtiar’s filmmaking abilities, but it does, in the absence of a fuller archive, get us closer to his ideas – his preoccupation with the struggle and development of a nation, and the condition and role of the individual ensnared within it. Moreover, the processes of intertextuality and détournement (and humour) at play in it gesture towards some of the latent, underexplored ways that erasures of a tragic nature can be playfully navigated, thought through and, to a small degree, overcome.