A new show at MoMA PS1 asks if art can help us understand contemporary life’s sensory overload

Three prosthetic penises, dozens of junked circuit boards, yards and yards of silver cellophane and a surplus of red fire extinguishers conjure unrestrained manufacturing and technological excess in MoMA PS1’s The Gatherers. The 14 artists in this exhibition respond to contemporary life’s sensory overload with works – some exuberant, some muted – that range from loose and lyrical to hypertechnical and encyclopaedic, though all of them serve as containers for a surfeit of feeling that cannot be processed in everyday life. The show’s title evokes a preagricultural past and likens the artists to a nomadic group of foragers. The international roster is indeed peripatetic, composed of wanderers – from Tbilisi, Los Angeles, Dangdong, London, Stockholm, Vilnius and elsewhere, though many have made their way to New York and Berlin – who traverse the postindustrial landscape in search of materials for creative nourishment. It shows. Everywhere indicators of urban grit and capitalist excess coalesce with a longing for nature and the bygone pleasures of home.

An ambivalence towards overabundance pervaded the show and its accompanying texts: too-much-ness means waste and a warming planet, but it also leads to material possibilities and the very foundations of creativity. Georgian artist Tolia Astakhishvili is particularly inclined towards spillage. Wicked Plans (2025), the first of two new site-specific works for the show, fills an entire room, the walls lined with raw building material, adorned with taped-up personal snapshots and enigmatic scrawl: ‘mood curriculum’, ‘small things’, ‘missing Mississippi’. Fire extinguishers dusted with white fire suppressant sit at the edge of an empty trough. In the corners are rolled yoga mats, bins full of dishware and fruit peelings and other odds and ends. The effect is of an abandoned dwelling in a state of transition or postemergency – the walls unfinished, the trash and packing boxes waiting for relocation. Light streams in from the windows, which overlook Queens and bring the grit and industry of the city itself into the work. The decaying fruit peels find a corollary in Astakhishvili’s other installation, dark days (2025), which resembles a concrete air shaft, a hollow rectangular prism filled with and surrounded by discarded objects. The exterior is littered with keys, dollhouses and fake miniature trees. Some of the trees look burned, some are still green, but all seem destined for the dumpster. Throughout Astakhishvili’s work, the natural world is reduced to playthings and rubbish, while communion and domestic life are mere memories, preserved in photography and toys.

Natural elements and a sense of nostalgia similarly pervade a gallery of sculptures by Los Angeles-born artist Ser Serpas. it festers while it stances up in that tree (2025) features a black tube that appears to embrace a white ladder and several tree branches, one of which is placed inside a black umbrella stand. Nature, in other words, is harnessed. A sled drowned in silver cellophane, in a work titled tube of brief cadavers made sadder still (2025), suggests a ‘Rosebud’ moment of tenderness and meaning amid avaricious adult concerns. Despite their scale and sprawl, Astakhishvili’s and Serpas’s works do not seem excessive, egomaniacal or inappropriately messy. Instead, these artists simply meet the moment, channelling the hectic, never-ending anxieties and non sequiturs of contemporary life into meaningful new forms.

More muted are works by He Xiangyu, Nick Relph and Klara Liden. He, who was born in Liaoning Province, China, contributes a precise presentation of smooth, erosion-marked rocks mounted in metal loops that unite them like small planets in an orrery. Here, the erosion rings, signifiers of environmental shifts, become aesthetic elements. The refinement echoes the spareness of Relph’s process. The London-born artist used a portable scanner to capture city surfaces, such as ‘cash 4 cars’ flyers and gas meter covers. From these scans, Relph made dye-sublimation aluminium prints. Glitches defamiliarise these texts, catching them in fragments or in off-kilter format. Liden takes a different approach to urban signage, bringing street signs directly into the gallery. The metal and plastic sculpture Untitled (Haltestelle) (‘stop’ in German; 2024) features grit-covered panels with a faded bus symbol and time frame for which, ostensibly, certain parking restrictions and traffic patterns once applied. Removed from its urban habitat, the sculpture appears as a yellow pole mounted with white plastic blocks, operating within a minimalist vernacular, a street sign without the street, or clear signage.

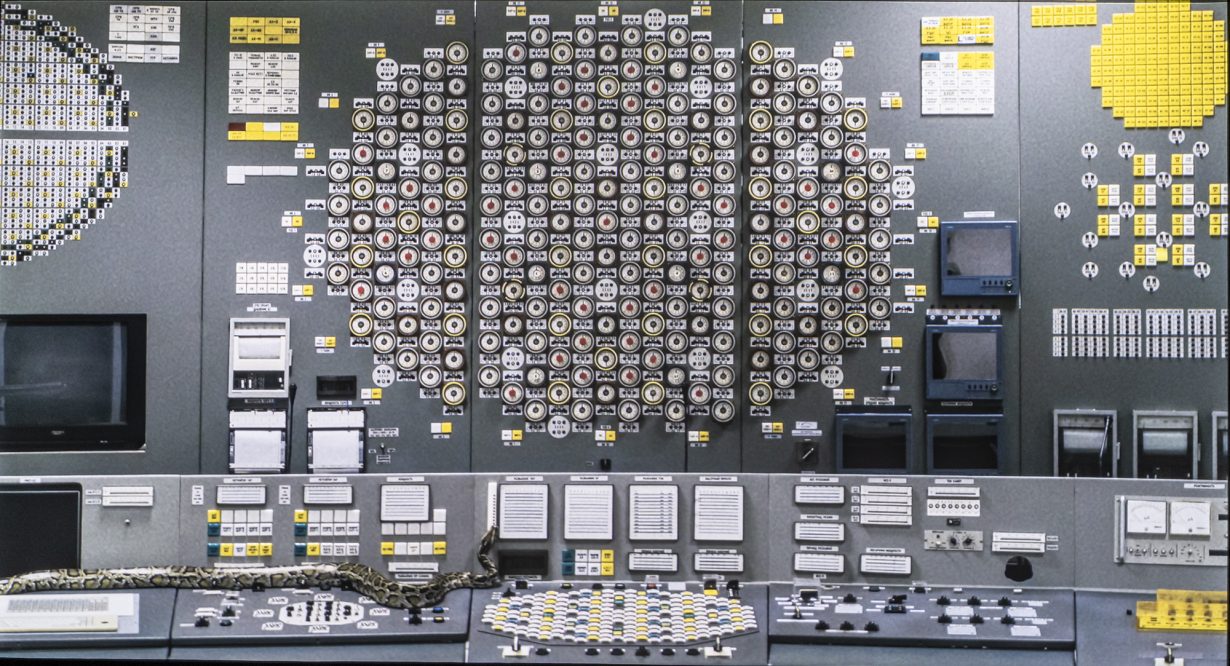

As the museum comes to seem an absurd enterprise in an increasingly inhospitable world – a repository for rocks and cast-out objects that even the city street won’t take – Emilija Škarnulytė’s Burial (2022) offers something of a way out. The Lithuanian filmmaker integrates eerie, futuristic shots of a burial site for radioactive waste with gorgeous scenes of the natural world. Rows of vessels and racks of clothing suggest curating within an institutional or domestic setting, while in other shots a snake flicks its tongue and moss grows thick on sedentary stone, as if to say, ‘There is still life out there’, teeming and threatening and green, if we stop categorising and catastrophising and go out and look for it. These striking moments in Burial offer some of the few rare glimpses of beauty to be found in The Gatherers, an exhibition that operates much more from a sense of mystery. By carefully suspending striped rocks above the ground, assembling domestic artefacts in a particular heap or juxtaposing discarded objects just so, these artists bring out the strangeness that’s too often glossed over in our algorithm flattened and information-glutted world. In this sense, artists who hoard offer a model for a more conscientious way to deal with the material and symbolic output of our own lives – and a call to reconsider our excretory habits. In this advanced age, when digital devices can answer most questions with stunning accuracy, they remain unable to respond to the query artists engage every day: what in the world to make of all this?

The Gatherers at MoMA PS1, New York, through 6 October