Indonesian artists are developing new and diverse responses to politics, culture, locale and form, centred around the conjunction of artistic autonomy and a socially-engaged commitment to responsibility

Ruangrupa’s artistic direction of Documenta 15, the five-yearly art exhibition which opened in Kassel, Germany, in June, introduces a global audience to the conscious collectivity that has been a feature of modern Indonesian art since the early twentieth century. Appropriating the idea of the lumbung, or communal produce-storage barn, ruangrupa has developed an artistic direction that fragments and delegates creative input, drawing on the resources of a community of art collectives from Indonesia and around the world.

In Indonesia’s creative and intellectual circles, collectivity’s roots are to be found in the archipelago’s rich and diverse agrarian-subsistence cultures, with links also to past Hindu-Buddhist civilisations. Embedded concepts like gotong-royong (mutual cooperation) and sanggar (creative communities) were elevated by the communitarian values that underpinned the anti-colonial independence movement during the first half of the twentieth century, and in Indonesia’s subsequent nation-state.

However, like lumbung, which has also recently been appropriated by the government to describe a controversial ‘food estate’ programme for increasing agricultural production, these embedded concepts that dominated the emergence of modern and contemporary art in Indonesia have remained sites of contested interpretation. They encompass an intriguing conjunction of the artistic autonomy championed by modernism in Euro-American ‘centres’ and a socially engaged realism with concomitant responsibilities to society.

In 1969 eminent Indonesian art critic Sanento Yuliman pointed out that even if a singular framework for the ‘Indonesian-ness’ of Indonesian painting could be determined, ‘there would still be artists who would deliberately deviate from it’. ‘Why not several frameworks, why not many?’ he wrote. ‘Is it not possible that Indonesia contains rich and unknown facets and concerns… including those that are mutually oppositional?’ In his 1970 analysis of the emergence of abstraction, ‘Seni Lukis Di Indonesia: Persoalan-Persoalannya, Dulu Dan Sekarang’ (Painting in Indonesia: Issues Past and Present), Yuliman went on to conceptualise a complex artistic continuity that alerts us to the ways in which modernism in Indonesia diverged from the rupturing and universalist tendencies it showed elsewhere. He identified its earliest precursors in the attitudes of one of the nation’s earliest modern art collectives, PERSAGI, the Association of Indonesian Draughtsmen. PERSAGI was founded in 1938, as Indonesia’s nationalist movement was gaining momentum, by the painters Sindudarsono Sudjojono, known as the father of Indonesian modernism, and Agus Djaya.

Yuliman quotes PERSAGI painter Basuki Resobowo, who in 1949 argued that the difference between ‘the teapot’ and ‘the painting of the teapot’ lies in their functions: ‘The teapot on the canvas has other obligations… the line and colour that we intend to arrange harmoniously (a unity of emotion) functions to fill the field of the canvas.’ This, wrote Yuliman, shows that ‘the development of painting in Indonesia has, since PERSAGI, prepared the ideas and sensibilities – let’s say it prepared the climate – for the development of a number of abstract paintings’.

Yuliman later identified this continuity as an ongoing ‘artistic ideology’ that respects the artist as an individual; and holds the belief, perpetuated through the teachings of the sanggar and institutions, that ‘visual elements and their arrangement, regardless of the object they depict, can evoke, declare or convey valuable emotions, feelings or artistic experiences’. In time, this was an ideology that extended beyond the canvas.

Thus, PERSAGI and the conception of sanggar both prepared the climate for the abiding importance of dual attention to collectivity and the individual in Indonesian art. Sudjojono’s own charismatic personality and strong nationalist sentiment, coupled with the progressive teacher-training he gained at the Taman Siswa school in Yogyakarta (inspired in part by the educational philosophies

of Rabindranath Tagore), made him a natural leader in a number

of sanggar.

Sudjojono’s principle of Jiwa ketok, or ‘the visible soul’, clearly linked aesthetic beauty to social truths. In the late 1930s he decried the beautified landscape-painting genre known as mooi Indië (beautiful Indies): ‘… our painters only imitate the works of these foreign painters and serve the needs of tourists… They are people who live outside our real life. But fortunately a new generation is coming up… a generation with new and fresh ideas… that will dare to say “This is how we are”.’

The focus on social responsibility combined with artists’ autonomy meant that artists from the early nationalist period (the 1930s through to the 50s) were seen as interpreters of society’s needs. During the 50s and 60s, these tendencies were institutionalised as leftist organisations gained political power following the declaration of independence in 1945. The Institute for the People’s Culture, or LEKRA, in which Sudjojono was a prominent figure, mandated its members to ‘Go down below, through interviews and in-depth investigation of the conditions and aspirations of the people’. Known colloquially as turba (an acronym derived from turun ke bawah – ‘go down below’) this practice inspired creative workers across all fields, but it also became a millstone for those who sought less prescriptive expression. Those who did not adopt the turba approach found funding and exhibition opportunities hard to come by.

With the rising influence of the Communist Party and the dominance of leftist organisations attracting censure at home and abroad, a series of conspiratorial manoeuvres conducted between politicians and the military led to an anticommunist purge in late 1965, conducted with unspeakable and indiscriminate violence across the archipelago. Turba, with its socialist aspirations but fundamentally classist approach, was able to continue in the new authoritarian regime’s developmentalist politics. Like gotong royong, it was co-opted into the linguistic framework of the New Order, used to describe politicians’ visits to underprivileged communities for photo opportunities. Artists, if they endured, moved to less overt tactics; collectivity survived.

In 1974 a collective of art-school students, Desember Hitam, boldly sent a letter mourning the death of Indonesian painting to the organisers of Indonesia’s largest selective painting exhibition (and were expelled as a result). By 1975 they were members of the GSRB (Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru, New Art Movement), whose manifesto stated that they were ‘striving for a more alive art, in the sense of demanding attention, natural, useful, a living reality throughout the whole spectrum of society’. PIPA was a shortlived collective of 13 artists including several members of GSRB, whose confrontational exhibition 1977 in Yogyakarta was banned just two days after it opened, as were many exhibitions overtly critical of the New Order regime and its cronies.

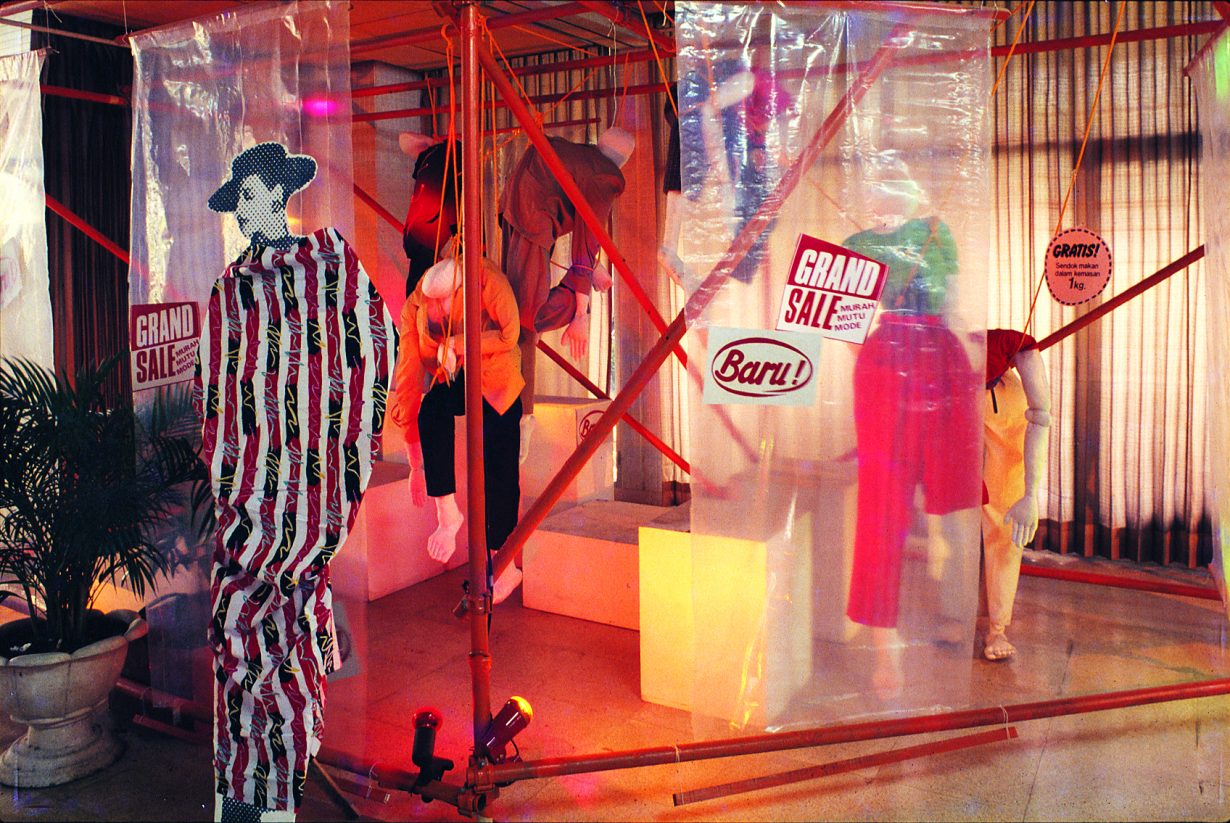

These three groups had in common an enthusiasm for interdisciplinarity, experimentation with form and medium, and a focus on concept over form: installation and found objects became the language of their art. In his catalogue essay for GSRB’s 1987 exhibition Pasar Raya Dunia Fantasi (Fantasy Supermarket), artist and critic Jim Supangkat reflected that what had carried over from the group’s earlier work was ‘a manifestation of exploration, opposition to elitism and revitalising pluralism in fine art through practices of art in everyday life’.

During the 1980s, collectives and individuals began using social-research methodologies, collaborating with other researchers and NGOs to address pressing issues. The artist Moelyono’s work with rural villagers was reinterpreted through the lens of progressive Brazilian pedagogist Paulo Freire and became ‘conscientisation art’. Performance artists in Bandung conceived of events that came to be known as jeprut, which were roughly analogous to, but less predictable than, the ‘happenings’ of their peers overseas, appearing unannounced in public spaces, a radically subversive act in an atmosphere of authoritarian vigilance.

By the late 90s, a thriving arts and cultural scene, and flourishing student movement coalesced to bring political criticism onto the streets. Indonesian president Suharto’s New Order fell.

One of the abiding debates that surround these kinds of practices – exemplified in critiques by art historians Claire Bishop and Grant Kester – is that of amelioration versus antagonism. Should artists bandage the wounds that capitalism and neoliberalism visit on society, or should they fight back? In Indonesia, many do both, often simultaneously. One example is Jatiwangi Art Factory (JAF), a collective of art-workers in rural West Java, and one of the organisations ruangrupa has invited to contribute to Documenta 15. JAF’s perspective is defiantly village-oriented, albeit with a sophisticated and organised framework with national and international reach. From 2008 they worked closely with the village-level government; one founding member was even elected village head. Visiting Jatisura in 2013, I witnessed an attempt by local bureaucrats (invited, but arriving tardy) to turn a community art event, in which residents were busily sharing creative drawings envisioning the village’s future, into an urban-planning focus group. JAF organisers prevailed, inviting officials to stay as observers only; such visits were not unusual, they told me.

Another example, the Babakan Siliwangi Residents Forum, active until 2013, was an interdisciplinary collective of artists, activists and other civil-society representatives who gathered with the specific goal of protecting an urban forest in Bandung city from the fulfilment of an infrastructure development permit. Under the guidance of their appointed chair, artist Tisna Sanjaya, the collective organised a creative festival and a ‘long march’ to the town hall, carrying graffitied panels purloined from the developers’ zinc fence. Five days later, at an exhibition organised by the Forum, candidates in the upcoming mayoral election signed their commitment to revoke the permit – a pledge honoured by the newly elected mayor.

These oscillating relations with authority are strategically antagonistic and ameliorative, again undermining binary interpretations of collective and individual practice in the social and political sphere. Beyond overt social-engagement, the Indonesian art scene also fosters a range of collectives that give succour, peer support and often shelter to artists and their work. Ace House Collective – whose membership includes painter Uji ‘Hahan’ Handoko – is one example, alongside printmakers’ collectives Krack! and Studio Grafis Minggiran in Yogyakarta, and Grafis Huru Hara in Jakarta. In Bali, Klinik Seni Taxu (Taxu Art Clinic) collective was formed out of disillusionment with preceding collectives of Balinese artists who were seen as too self-exoticising. Other collectives, like Kongsi Benang (Thread Syndicate), bring artists together at specific stages of their careers and lives – in that case, textile artists caring for young children – and disband or recede as needs change.

Indonesian artists are developing new and diverse responses to politics, culture, locale and form, claiming a place for distinctive practices that is increasingly recognised at the forefront of global contemporary art practice. The work taking shape in Indonesia represents an exemplar for understanding collective and socially engaged art practice, a lens through which to consider the significance of movements of collectivity and their implications locally and globally: where they have come from, and where they might lead.

Documenta 15 is on view in Kassel, Germany, through 25 September