As Ligon prepares to open his first exhibition in Hong Kong, he talks about race, place, meaning, legibility and why looking at art should be a form of labour

In a public conversation organised at The Church, Sag Harbor (NY), last July, Glenn Ligon was asked about the challenges that viewers face when interpreting his work. In response Ligon said, “Do the same work you do to understand de Kooning.” Ligon demands that viewers be prepared to work when in the company of his projects. Over the past three decades and across multiple continents, the artist has introduced audiences to the prophetic insights and language of Black philosophical thinkers. Ignoring the limited basis through which most people would or could understand the drive and commentary of James Baldwin or Zora Neale Hurston, Ligon’s ever-intimate critique and thinking about every facet of their oeuvres is not to issue a corrective or provide a legible monolithic trope of Blackness. Rather, Ligon riddles the texts through material erosion to include all viewers in questioning their personal subjectivity and position in their realities. We are currently in a world bent on waste and expanding extremist beliefs. This state ossifies the human imagination and inhibits our ability to inquire what things do and could mean to us. But Ligon initiates viewers into a process of uncertainty and transformation as a necessary exchange of play and ritual. It is as much about you freeing yourself from a closed system of meaning, especially systems that produce false certainties around race, sexuality and being. Here, ahead of the opening of an exhibition of his work at Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong, Ligon speaks about how his work is given subjectivity through the interpretations of others, and the new artistic distances to which he is pushing foundational texts.

ArtReview Asia Tell me about the upcoming exhibition.

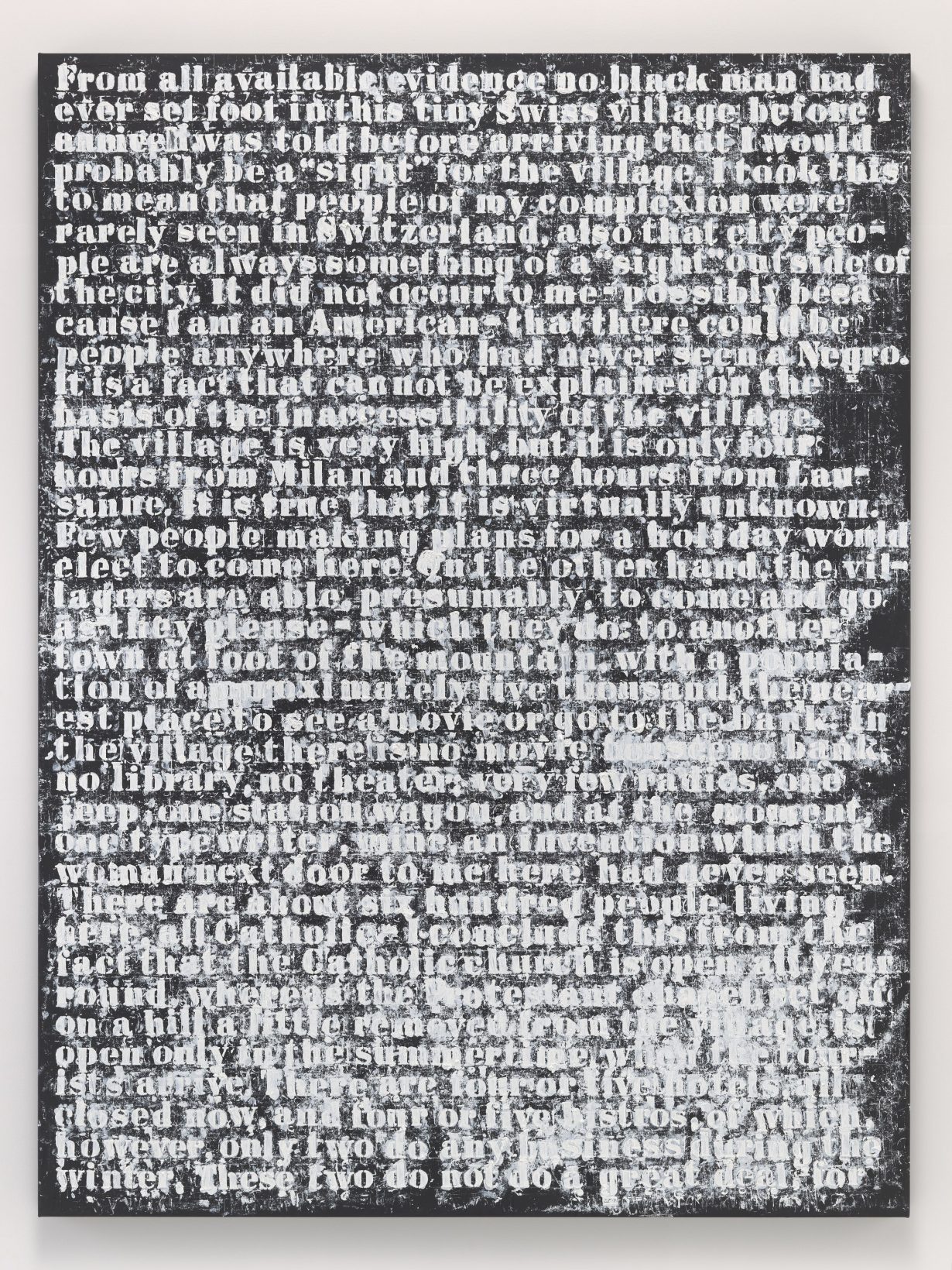

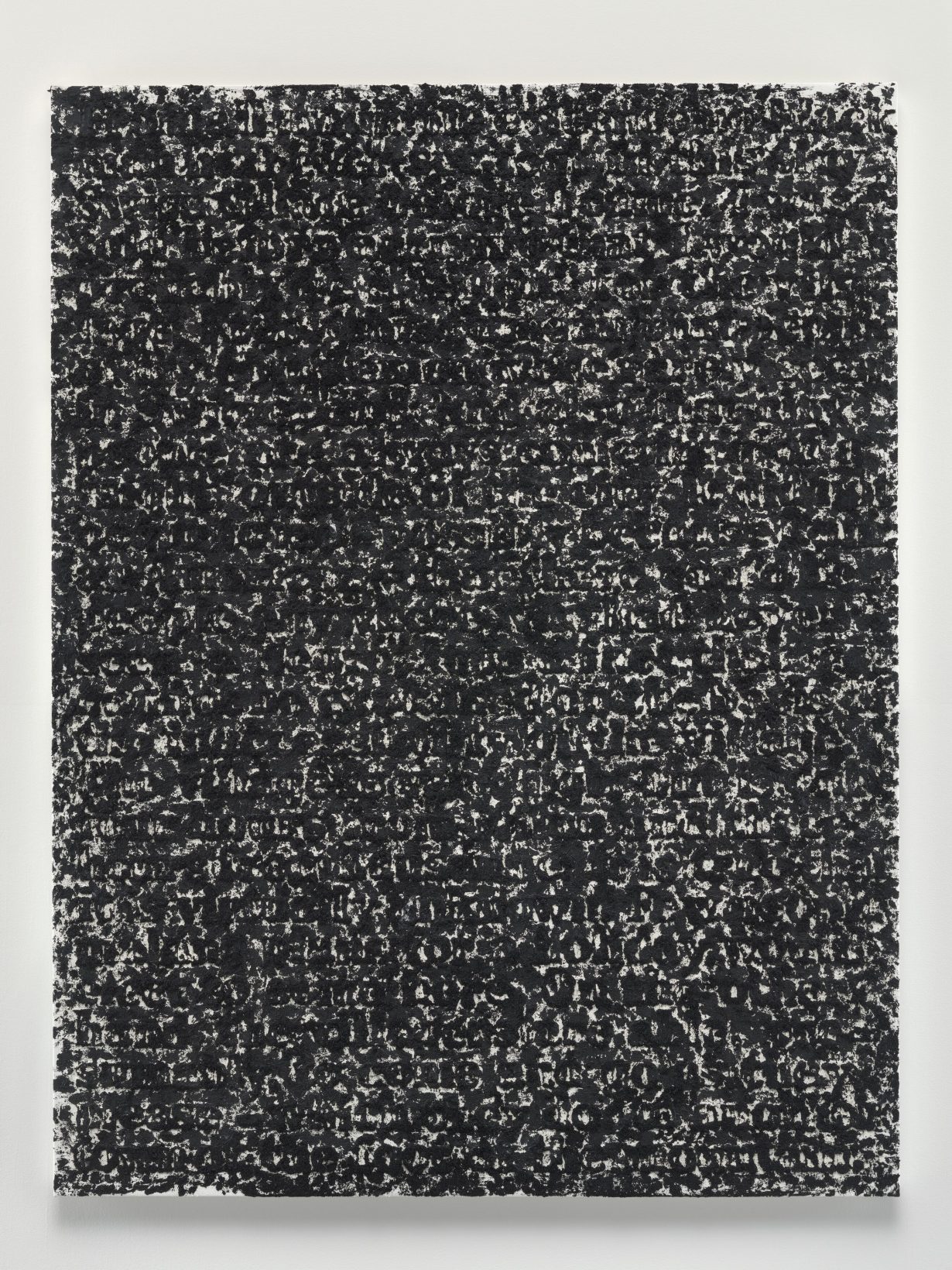

Glenn Ligon The show features paintings from the Stranger [1997–] series and works from a new series called Static [2023–], which are much more abstracted, text-based paintings. Then there is a series of graphite and carbon rice-paper drawings that are rubbings of existing paintings. The Static series came out of a white-on-white Stranger painting that I did seven or eight years ago. For various reasons I felt it was not working and put it away. Around a year ago I pulled it out of the racks and worked on it again by rubbing black oil stick over its surface. The black oil stick didn’t necessarily highlight the text in the painting, so the work became much more about patterns, static. Static is a strange concept for a younger generation. I have a nine-year-old godson who lives in Japan, and I had to explain what static was to him because he doesn’t listen to the radio and has never seen a TV station go off the air at the end of the night. But this idea of a transmission that’s not getting through, or scrambled information, is interesting to me.

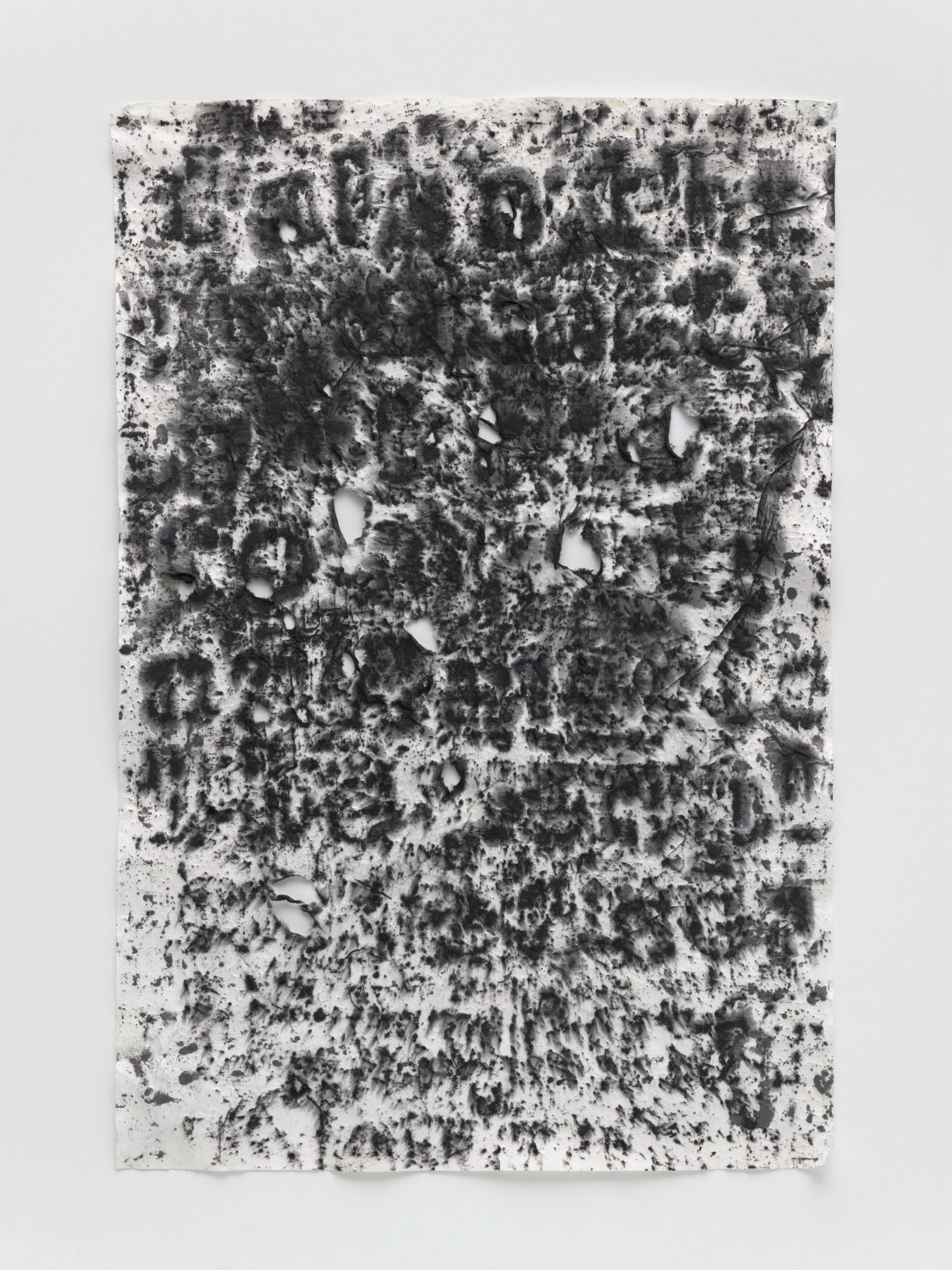

The drawings that use rubbing as a technique started because a friend went to Xi’an, China, which has an area where there are very ancient monuments where calligraphy students would be taught. He sent me these incredible rubbings of these stone monuments where there are corrections because they were carved by students and then the master would come in and correct their calligraphy.

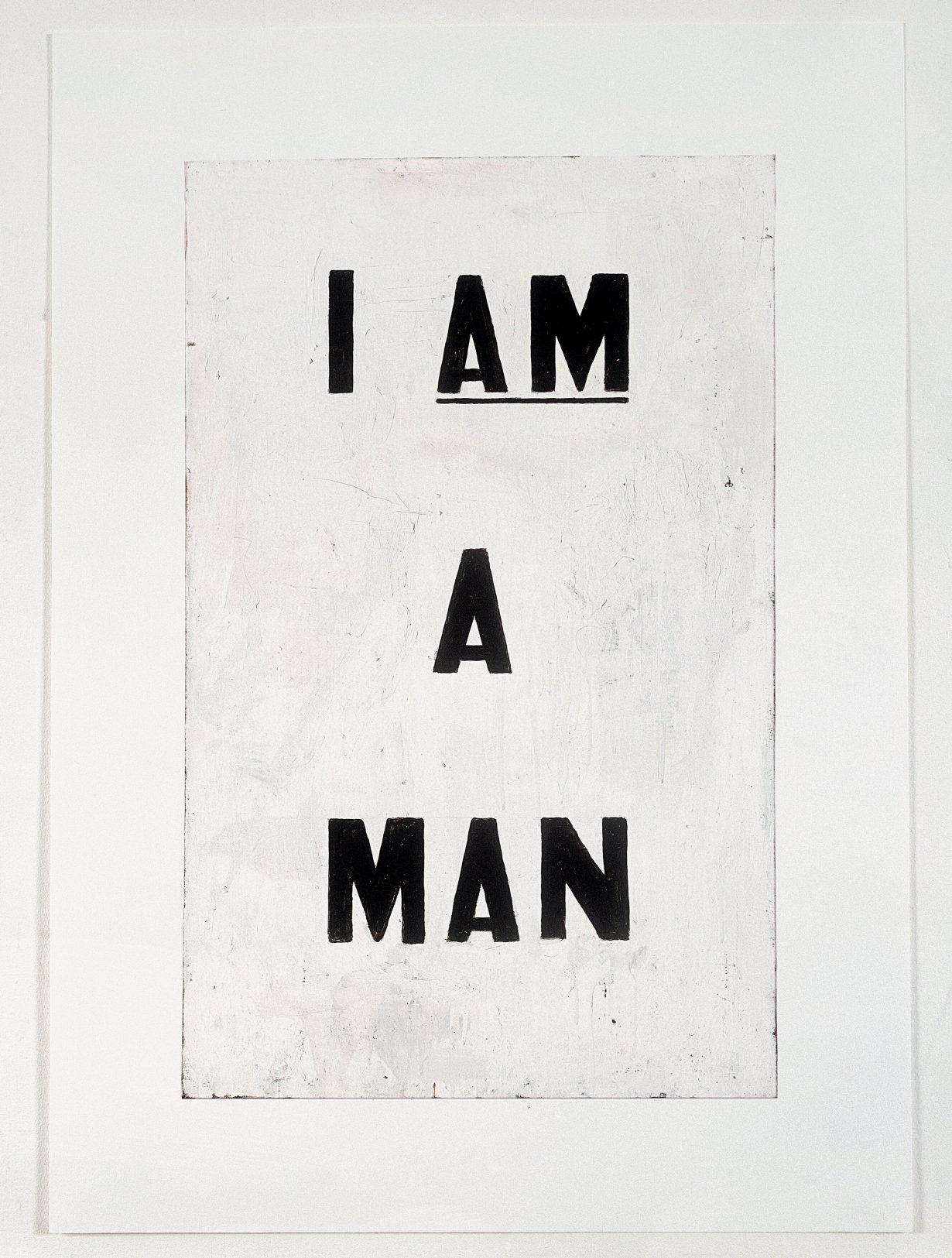

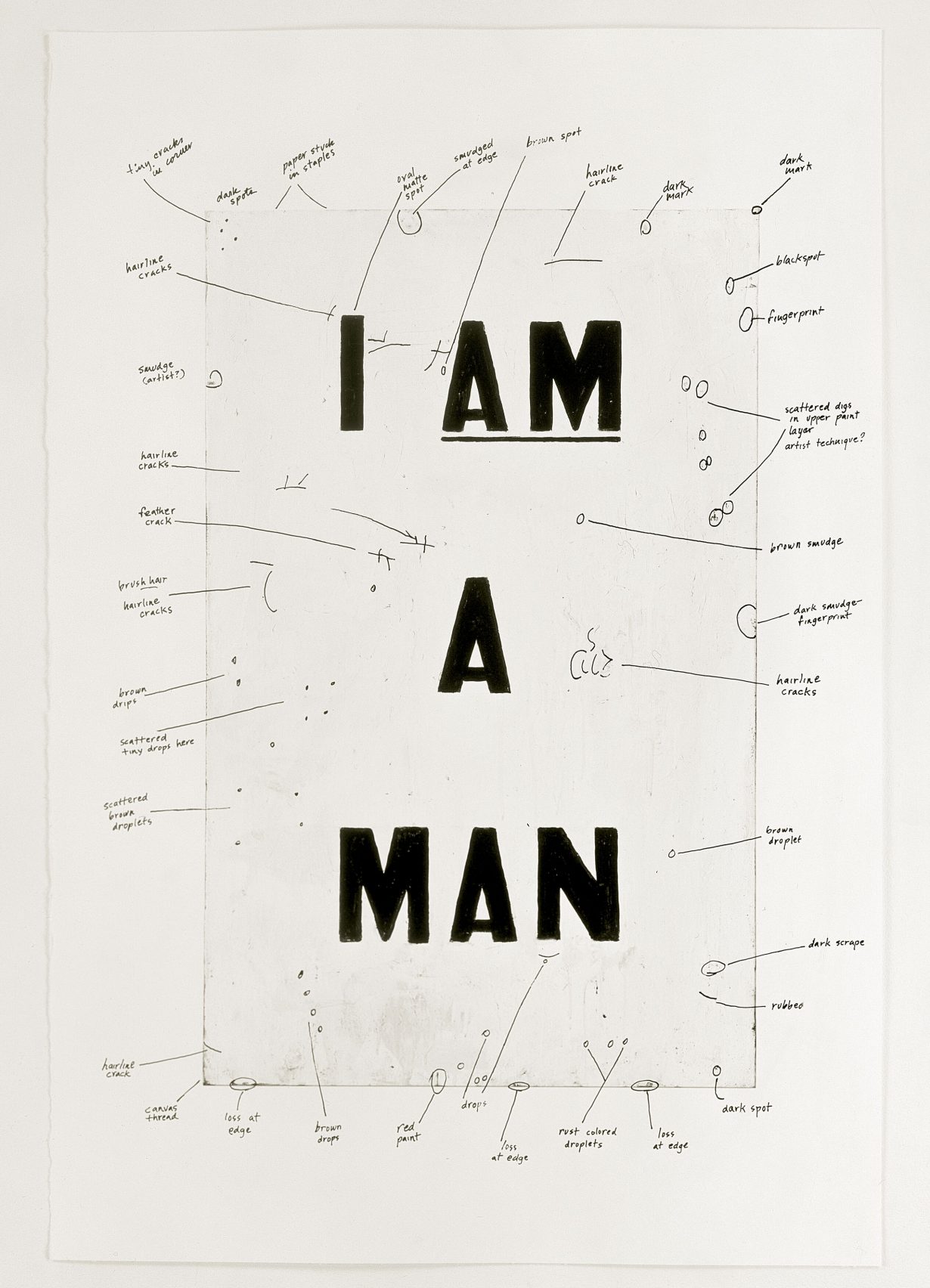

ARA It also resonates with the annotated ‘I Am a Man’ piece [Condition Report, 2000].

GL I was thinking about that too. I’m also doing a show at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge that’s about annotations. I was looking at that ink rubbing in my studio for a long time and trying to figure out how to make one of my own.

You see, when you’re producing a rubbing of, say, a tombstone, you’re pressing against an incised flat surface. But my paintings are all impasto – the surfaces are built up. I realised that if the text on the painting was flat enough, I could wet rice paper, put it on the surface of the painting and then press down into the negative space in and around the letters. There are some precedents here, like Jack Whitten, whose work I admire a lot. Sometimes the text that I’m rubbing on top of appears very clear, and sometimes, if the paper’s too wet, the graphite and the carbon smear. It almost becomes like a watercolour.

ARA Something else that also occurred to me is that the abstract is associated with illegibility and dissociation in the background of the ideas that your work brings up.

GL I think one of the things that I was thinking about when I first started making work with texts in the 1980s was how little-known those authors were. I mean, they’re known if you’ve taken African-American Literature.

ARA Or you had a family that was about that life.

GL About that life, exactly… Part of the desire in that early part of my career was to put these authors who I was deeply engaged with into the space of art, so that when one walked into a gallery or museum and my work was there, those were the authors you’d have to engage with. As the work travels farther afield and time has passed, it circulates in very different kinds of ways. Baldwin’s visibility in the 1980s is different from how we view Baldwin now. His presence in contemporary culture is very different from when I first started out. In a way, my original project was about visibility – which I guess was always a bit ironic since text is mostly illegible in my work. I feel like when I’m using a Baldwin text now, I use it as the ground on which the painting or work on paper is made. Consider my rubbings: if I’m creating a rubbing off of a Baldwin painting, the painting is literally the ground on which I’m making this other artwork. The Static paintings also have Baldwin text underneath them. I’ve absorbed Baldwin’s words, and the artwork gets made on that ground that he has provided for me.

ARA To what extent do you think your experimentation with the materiality of the impasto of your previous series is like a critique of the text itself? Do you have frustrations with Baldwin or Hurston?

GL In Baldwin’s ‘Stranger in the Village’ [1953], he never mentions that the owner of the Swiss chalet he’s staying in is his quasi-lover; his gay-ness is not apparent in the essay. Though one imagines that, in the village, there must have been questions… Baldwin tries to do everything in that essay. It’s about colonialism. It’s about his relationship to European culture. It’s about his relationship to the villagers. It’s about his exile from America. I think the difficulty that I stage in my paintings means you have to struggle with the text. Baldwin’s aim in writing this essay is to make things clear. And I think in some ways that’s always going to be a failed project. There’s always going to be a kind of opacity in the essays, because he’s trying to do something so panoramic in nature and tackle topics that are too big. There are always going to be blind spots in his work. In some ways, I feel like the difficulty I stage in my paintings, how hard they are to read and how you have to struggle to read them, is the struggle to understand anything about race or identity. The topics are difficult; they are not fully knowable or known. Toni Morrison talks about the idea that Blackness is not already known or fully knowable. It’s reinvented constantly. The idea that Black people as a subject matter are knowable and therefore exhaustible means folks can say, ‘We’ve done you, we understand you. We get you…’

ARA I think that where you sit in the art-historic landscape is so interesting. You’re influenced by late Impressionism that emerged after the end of slavery in the United States and when Japanese woodblock prints and exposure to non-Western arts are eroding this centuries-long dedication to figuration. At the same time, Black people, despite it being illegal for centuries for them to be literate, are expected to exhaust ourselves through slave narratives. Can you speak to how this moment influences your sense of legibility and opacity in your career?

GL I think, just on a kind of formative level, you’re right. When I was in high school, I went to after-school classes at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. European painting was front and centre with Cézanne, Matisse and Monet’s work hanging in the galleries. The message was, ‘This is the important stuff’. I became interested in those artists, partially, because of the oscillation between figuration and abstraction in their work. But also, I think, because I hadn’t been outside of the United States, so French painting was a way to travel. Also, I’m not a figurative artist. Text is my figuration. The project of a lot of Black American literature, especially in slave narratives, is an insistence on figuration, on ‘representing’. But that focus on representation is a constraint and it implies a certain kind of violence, in that the idea behind those narratives is, ‘We have to convince white folks that we’re human’, which, as a premise for writing one’s autobiography, is deeply problematic. It’s something that Toni Morrison deals with when she is writing Beloved [1987]. She says, ‘I want to pull the veil off of the violence of slavery, that those earlier narratives can’t really do.’ Those narratives are trying to convince folks and garner sympathies, so they can’t really go into the kind of violence that actually happened during slavery. Let’s talk about the scars on Sethe’s back. Let’s talk about why it was more important for Sethe to kill her children than to let them be sent back into slavery.

ARA I recall you mentioning hip-hop and graffiti, from your early life, but you also said you weren’t allowed to participate. I just tried to think, what was Glenn Ligon’s commute like from the Bronx down to Walden every day? What did he see?

GL I think it was an early influence that I didn’t know was an influence. My family grew up in the Forest Houses in the Bronx near Mount Morris High School. Trinity Avenue and East 165th Street, mid-South Bronx. My mother said, ‘I’m sending you to a private school that’s an hour and a half away from our house because I’m trying to get you up outta here.’ So from 1st grade to 12th grade, I went to Walden, a private school on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. I could understand her desire to keep me off the streets, but I had to go outside to go to school, and I had friends and relatives who lived in the neighbourhood. You could not get on a subway car during that time that wasn’t tagged top to bottom. It was also the beginning of rap and hip-hop… Fat Joe grew up in the housing project I grew up in. I didn’t know him, as he was a little younger than me, but he talked about DJ parties in the playgrounds in our neighbourhood. I probably heard them from the windows of the 11th floor apartment we lived in, but I wasn’t allowed to go out. But I think the idea of visually playing with language got into me because of the graffiti tagging. The best graffiti was illegible to me. Like, what the fuck is this? It was all about the elaboration of fonts: graphic inventiveness, scale, colour. I don’t think I understood it as valuable in an artistic context, because art, for me, was at places like the Met. But in retrospect, the lessons got absorbed. And someone like [Jean-Michel] Basquiat, when I first saw his work, I realised, ‘Oh, this is a direct connection to things that I grew up with’, but I didn’t know you could use that in the art space that he was inhabiting. So he was an important influence. Not that my work looks anything like his, but…

ARA The permission…

GL The permission to think about text as a primary medium for making one’s work.

ARA It is hard for me not to think of your work in relation to concrete poets like Nicanor Parra, Guillaume Apollinaire, Dom Sylvester Houédard, for example. I wanted to explore that idea of semiotics as a possible cognitive dissonance with you. You’re asking viewers to search, to ask, to look, through the negation of understanding. And so I wondered, what would Mr Ligon say about such a thing, doing the work that he does?

GL There’s the question of opacity, too. Of just recognising that there are things in the work that either you know, or you don’t know, and things that will remain hidden unless you’re deep in. When I first started out, there was a demand for artists of colour to be explicit, to be upfront. It was all about telling folks who we were and what we were doing. Over time, that shifted. Now I feel like folks got to come to us. That’s a super interesting development, which for me is tied to the rise of rap and hip-hop, which was all about inside knowledge. I think culture is so fast now, too. I was on a panel at the Brooklyn Museum recently, and we were talking about slang and how easily it’s co-opted. Someone on the panel said, “But that’s ok, because five minutes later, we’re done with that way of saying something and onto the next.”

I also think about the jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker. Part of the reason why he played so fast was so he couldn’t be imitated. He’s like, ‘Are you trying to do my shit? OK, I’m going to speed it up… play twice as fast. You can’t steal the shit if you can’t keep up.’ In general, Black culture is hard to keep up with, because it moves so quickly. But that is, I think, where its strength and vitality come from: that it’s about constant reinvention, and it’s about constantly moving on.

An exhibition of work by Glenn Ligon is on show at Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong, 25 March – 11 May