“I try to be a good artist, and to be a good artist I think you have to feel like you’re falling”

Seven years ago, I sent an email to the painter Josh Smith to ask about a possible interview. Four years later, I received a one-line response: ‘I will do the interview sometime if you like’. From that moment, it was another three years before we were able to find an afternoon to meet this past winter.

As we discuss in the following interview, Smith is resistant to socialising, and prefers to spend long stretches of time in his Brooklyn home, a largely windowless warehouse he’s transformed into a live–work complex. Throughout the building’s two storeys, he’s set up several spaces for his art: a workshop for building, a ceramic studio with a kiln, a casual studio, mostly used for storage, and a primary painting studio with a ping-pong table “for exercise”. The house also contains multiple lounges, kitchens and a large art collection, which includes a piece by Mary T. Smith (no relation) in the bathroom, and a living room tiled with Haitian paintings.

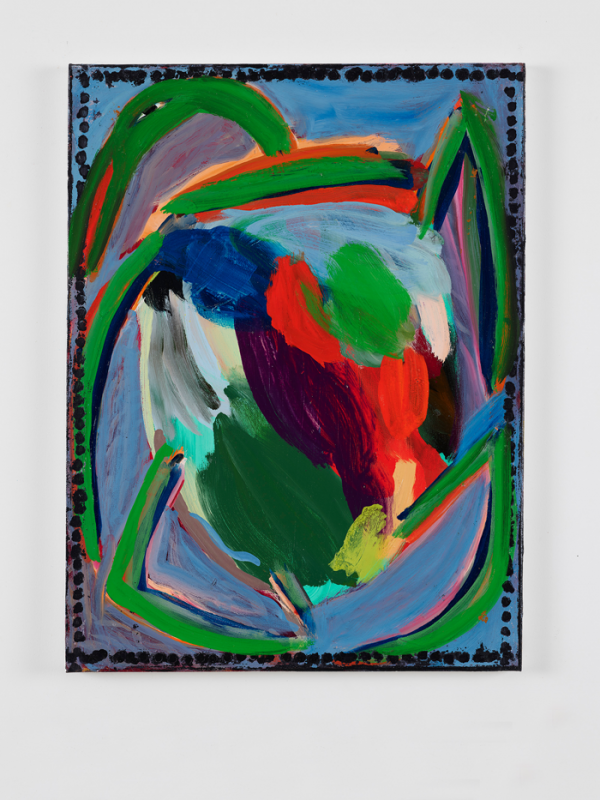

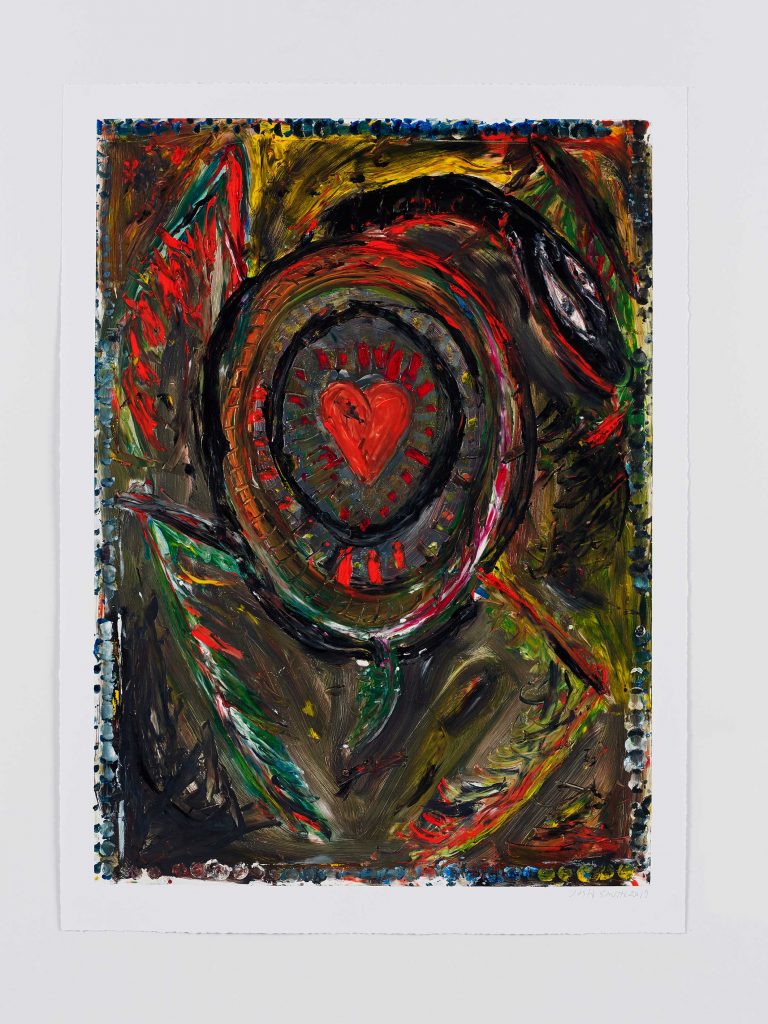

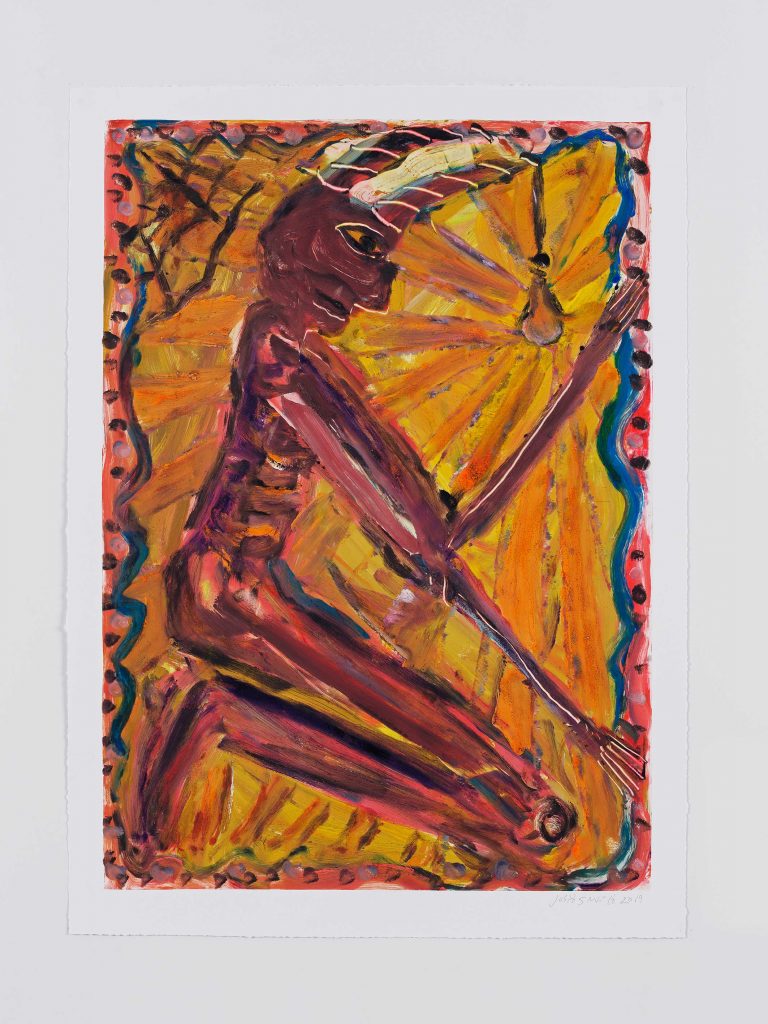

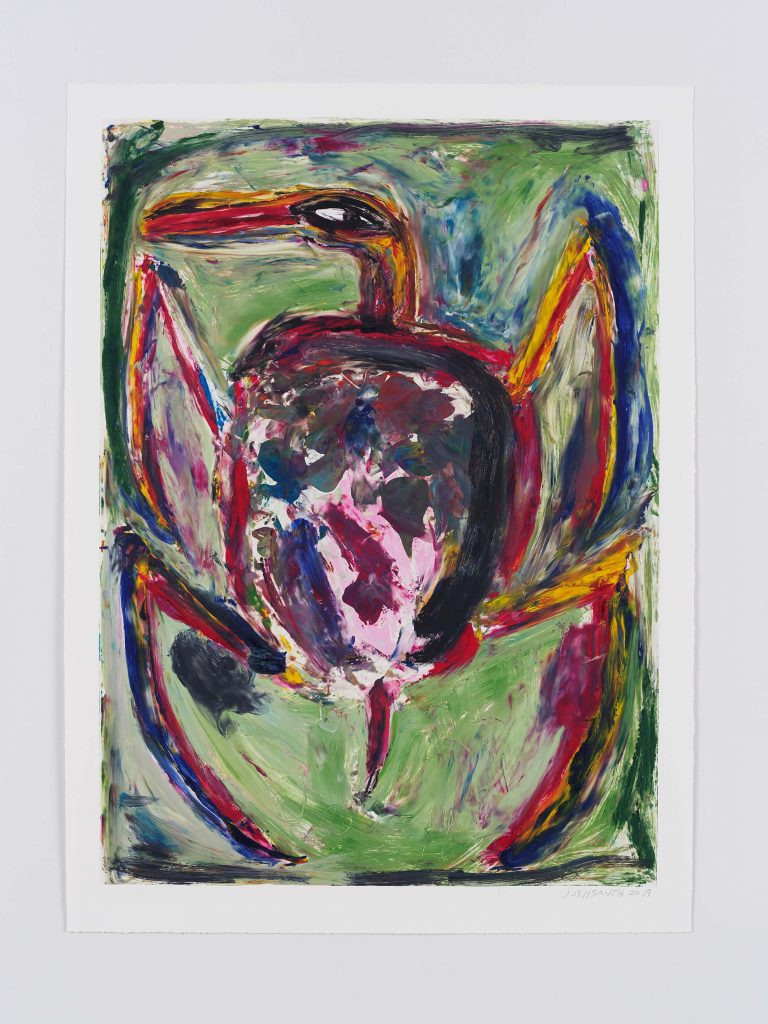

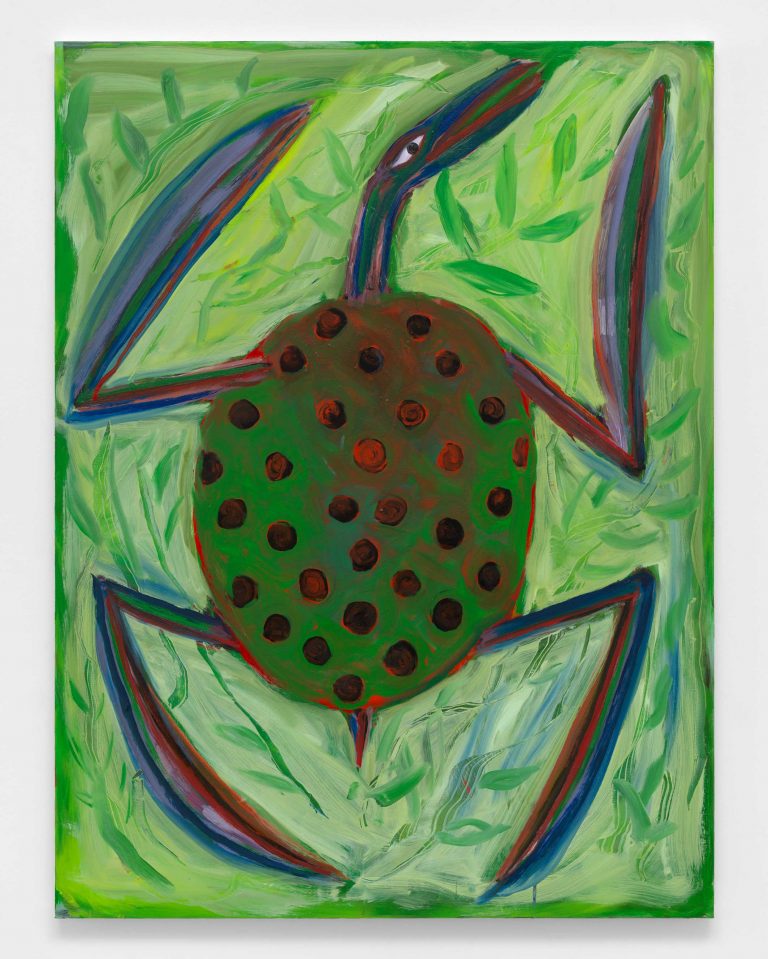

On the day we spoke, Smith’s studio was empty of new work, but I was able to flip through a few stacks of paintings from the various series he’s made over his career. There were some grim reapers, tropical sunsets, fish, devils and monochromes, all rendered in his loose, full-armed strokes. Not present was his early work: the abstractions, the canvases he uses as palettes or the paintings of his own name, the ‘signature’ works that are most often associated with his success.

Smith usually paints in batches of highly specific, simple subject matter – fruit, animals, land-scapes, myths – which often have the appearance of being made feverishly and in the pursuit of honest, unmediated expression. He works in this same way across collage, bookmaking and clay, using seemingly arbitrary content as his engine for accreting material. Taken together, his work suggests one man recreating the fundamentals of painting.

For our interview, we settled into his library, walled with grey metal shelves and filled with books: art, fiction, poetry and history. In the middle of our talk, he pulled down a monograph of some American Colonial painters and opened it to a portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart. “I wish I could do portraits,” he said, “but I’d have to be more patient.”

After the interview, Smith brought me down to the basement, where he grows an impressive variety of leafy green vegetables. For ten minutes, he carefully snipped until he had stuffed a plastic baggie filled with lettuces and chards, which he gave me as parting gift.

6 images

Locked In

Ross Simonini We’re sitting in this library, surrounded by books, almost all of which are artbooks. Do you read these or just look at the pictures?

Josh Smith Mostly I just look. You know how you read an artbook: you open it, you look at a picture, you read what’s around the picture, then you kind of lose interest. And there are periods where I read a lot. Like a lot. But that’s when I’m not smoking, not using, you know, any pot or anything.

RS Smoking isn’t good for reading?

JS Not even a little. I get hung up on every word and everything becomes so intensely interesting for me that I can’t make any progress. But other times, I’ll take a load of artbooks upstairs and read.

RS You get your input from books.

JS Yeah, because you need gas to keep going. I mean, you can see from the books around us, it’s a collage of everything I love.

RS Do you read non-artbooks?

JS What I like to read about is other civilisations and history. I love South American history and indigenous history. All the people who lived in America way before us. I listen to a lot of audio-books when I work. I think that’s just a great gift. That technology. I can just really learn so much. It’s like a child – having someone read something to you. I listen to a lot of nonfiction, but I can’t really do fiction when I’m working. Nonfiction books, you can miss a little bit here or there and it doesn’t matter so much. You can tune out. But in literature, the whole thing is so considered and thought out. In my life, I would never have time to read thick books about the Aztec culture. But on an audiobook, I can. And I mix it up with music too.

RS Like what?

JS I would say pretty much exclusively a synthetic type of hip-hop music. I don’t like very folky mu-sic in the studio. I also like 8-bit stuff a lot. I like to feel like I’m punching when I’m working, so mostly I like Southern and New York rap. These people are so young, and there’s such fresh energy in it. I think of those people like painters.

RS How so?

JS Just the way people dress and the way they develop personalities. The casualness of it. It’s like they’re pulling stuff out of the air, out of the back of their brain, and for me, all of that can be applied directly onto the canvas.

RS Do you consider your personality as it relates to your painting?

JS Well, I spend long periods of time alone, like maybe months. Sometimes I won’t leave my studio for six months.

RS You won’t leave this building?

JS That would be like a worst-case scenario, and it’s not healthy. So yeah, you kind of get delusional a little bit. Like, I know I’m not some rap guy, but you kind of lose touch with reality. I love that. I think that’s a luxury, but when you do go back out into the world, you realise how fucked up you are, ’cause you don’t know how to talk to people.

RS Does good work come out of these periods?

JS Of hiding out? Yeah. I have to do it to get my work done. Ideally, I’d be more of a person who works a few hours a day and then goes out for drinks with friends. But I have a social problem. I know really great people and I know this city’s teeming with wonderful people, but I don’t know how to access them necessarily. I have to work a lot to make sure that my work is really good. I don’t clock out. I call work being “locked in”. I’m not painting like all the time. I just, it’s just locked in, like, just waiting for work and thinking and digging around. It’s a lifestyle. I don’t have any responsibilities. I don’t have a family. I like to stay up all night when I’m working, because you’re the only person in the world at night. You don’t hear the cars outside or anything. I try to be a good artist, and to be a good artist I think you have to feel like you’re falling. Like you’re kind of slipping and falling. It’s uncomfortable and it’s kind of a sick lifestyle.

RS Are you most happy when secluded?

JS You haven’t seen me during these phases, like you’re seeing me now. In hindsight, yeah, there’s nothing like going into your studio with two bags of Fritos and six Red Bulls. And then, you know, you just work all night and just – you’re by yourself. I like to get stuff done. But then again, you emailed me years ago and it took me many years to write back. But I mean, I’m not a jerk. I’m just in a spiderweb. I’m not a spider. I’m just trying to avoid being eaten by myself. Eaten up! I mean, how do the great artists get it done? There’s also a lot of tricks that people do, and I don’t want to do those tricks.

RS Like what?

JS Settling into something and making a run out of it. Going your whole career doing one thing. It drives me insane that some artists are just repeating themselves over and over. I think it’s conservative.

RS What is it about the outside world that feels unattractive in these periods?

JS I just don’t feel like I have the time to engage in it. It’s like fasting or something. So, for the last show I did in New York – which was in May or April – I wanted it to be very good, so I had to focus. But I feel like all the shows could be my last show. There’s times when you’re a little more easygoing about it, but in New York, I feel like there’s so many artists and so many galleries, and my peers are here. And I don’t want them to think that I didn’t do the best that I could.

RS Do you enjoying showing work?

JS I think I like to show off. I want a receptive audience, and I don’t like mediocrity.

RS Do you just exhaust yourself? Is that why you feel like it’s your last show?

JS I mean, I also try to make work that is really bad, you know, like bad enough that it could go either way. I did a monochrome show, for instance, and I’m fortunate, ’cause I can roll through things. And a lot of artists don’t have the agility. But I don’t think I’ve closed any doors for myself. It would be hard for some people to change, and I can change.

RS You’re rejecting the outside world in your personal life, but reacting against it in your work.

JS I can spot trends really easily. And I don’t like trends. You know, people getting in other people’s footsteps too much. Like I don’t think that’s why you should come to New York. Make your own footsteps.

RS Is selling your paintings a way of being social?

JS I try to make my work so that it’ll appeal to a lot of different people: kids and adults. I want people to look at my work and understand exactly how it was made. I mean, ’cause you can see all the brushstrokes. I like my work a lot. It’s the thing I like most about myself. Really. I love the idea of my work in homes. I was in DC recently for tourism and went to all these museums, and all that stuff was protected. The stuff that we’re seeing, the old stuff, it went into the homes of wealthy people and managed to survive. Like, I love eighteenth-century and nineteenth-century American art. This country was just being made, and the art survived all that. And there were only a few painters, you know, you could count them on two hands. And it still looks so fresh.

Big Love

RS Do you ever show paintings that you don’t like?

JS Why would I show anything that I don’t like? That seems cynical.

RS Or maybe it’s an act of honesty, which is something you seem to value in your art. You’d be show-ing work that is not necessarily an expression of greatness, but an expression of failure, or falling, as you call it, which is a way of being vulnerable.

JS A lot of my work does illustrate my depression, especially the abstract paintings. I think abstract paintings are a supreme artform, but I don’t know if that’s really true, aside from a few artists in the middle of the last century. I think there’s still a lot of space there, that there’s still another step there that can be hammered down.

RS Do you look at contemporary work?

JS I don’t know how helpful it is to see that much contemporary art. I think it can really hurt you to see earnest people kind of missing so clearly. It bothers me. You know, the art, the energy expenditure and art materials, and you could see they’re trained well and everything, but they’re just missing. It kind of eats me up. It makes me feel guilty.

RS How much time are you spending in the studio?

JS Oh, probably about every day. Twenty minutes at least. But a lot of times I just come and get one of these racks and fill it up with books and bring it upstairs, just to learn.

RS What are you learning now?

JS How to take care of my body. So I’ve been reading a lot of books about health. I’m getting old and I don’t feel that good. No one teaches you diet and exercise in school.

RS Upstairs, in the studio, there’s a ping-pong table. You said you use that for exercise?

JS Yeah, I try. I try to use that. I lost a lot of weight, and now I’ve gained it back.

RS On purpose?

JS I think it was just stress. I lost like 60 or 70 pounds. And then when I saw people again, I think it scared them, you know? I looked so different. So I don’t want that to happen again.

RS Are you still a vegan?

JS Yeah. I’ve been a vegan for nine years. But I started thinking maybe I was depriving myself, ’cause I’ve been feeling so tired, just fatigued. So I don’t know. I love being a vegan, but it makes social stuff really hard – not drinking and being a vegan. The only thing I don’t like about it is the word vegan. It’s a stupid word. It’s sharp.

RS You told me that you use psilocybin mushrooms as a way of helping when you socialise.

JS Yeah, like, you go out, you just take a little bit, and you’re just more relaxed. I wish I could do it more often. You know that you get a tolerance for that stuff really quickly. You can’t do it every day.

RS Does it help with your depression?

JS Yeah, it does. I mean, I assume everybody has depression a little bit. I don’t want to say mine’s worse than anybody else’s, but Jesus, I think maybe mine might be worse than other people’s. I just think too much about things. And when someone does something mean to me, I just don’t understand it. I’m a coward, so I just keep myself out of the line of fire. I just put it in the art.

RS Do you think that you are progressing as an artist?

JS That’s such a good question. No. I think I’m the same artist. I think I’ve picked up more confidence. I’ve got better art materials, you know, brighter colours, and I’ve gotten more time. I think I’m the best artist that I can be for now, but I don’t think it’s good enough. Or else I would stop. I mean, the proof is someone like Jasper Johns or Louise Bourgeois. When I see an eighty- or nine-ty-year old artist that’s still doing stuff that’s fresh, I realise I haven’t even started yet, you know? But I have turned through some stuff pretty quickly.

RS Are you improving as a person?

JS I think I’m a much worse person. Or maybe I’m just hurt. I think I have a good heart, but I’ve lost my inner child. And that’s the quest I’m on now, to try to find my inner child again. I mean, I’m such a loving person, and I would do anything for anybody, but I’ve been hurt by people. They’ve done mean things to me that I don’t understand, and I’m not feeling like calling them out on it. So I just like internalise it all. I’m not really into forgiving shitholes.

RS Maybe the forgiveness is for your sake, not theirs.

JS Yeah, but fuck them. You forgive a bad person, they’re gonna fucking do something worse to you. Two seconds later, maybe. I’m also way too sensitive, you know, and I don’t really want to change that either. I don’t want to become less sensitive.

RS That’s what being an artist is all about.

JS And I have sacrificed a lot to be an artist, to be like this. Like I don’t have a family. I’ve probably seen my parents a handful of times since I’ve left Tennessee. And, yeah. You are totally right. You forgive people for yourself. But I mean, I don’t even think the people who I’m thinking of now, they did anything wrong. It’s all in me, you know? It’s all on me.

RS Do you want to have kids?

JS No. But when you get to be this age, everyone has kids. So you know, you don’t have options. Any relationship you have with someone you knew in your twenties or even thirties is fake. It’s kind of truncated, like, “I can see you between 7 and 7:15, but then you have to put Lucy in a bed”. It’s just not deep love, you know? And raising kids in the city is really tough too. Yeah, I feel like that’s kind of isolating, and also a lot of my peers are really busy. Everyone’s either out of town or recovering from some dramatic thing. It’s not a big love. You get that in your twenties. It’s just kind of missing now. It’s hard to have close friendships as an adult.

The Turnaround

JS Can I ask you, what’s the perception of me out there in the world? You can be honest.

RS For one thing, you’re seen as productive. You use quantity as a kind of material that’s essential to the work.

JS Yeah, that’s just what I do. Maybe other people are just not that productive, you know? And I have the luxury to, like, I have several galleries, and they move stuff.

RS Another way that people perceive you, I would say, is successful.

JS Well, to be successful, you have to give a lot away. I’ve given a lot away, and you know, I’ve been ripped off a lot and dealt with a lot of shady kind of situations, and I haven’t really kept a really tight control over stuff. I’ve just hammered, and not got hung up on every little thing or this or that.

RS This is related to the quantity, right? Somebody who makes three paintings a year would have a harder time with getting ripped off.

JS Safety in numbers, yeah. I learned that from my favourite artists: Picasso and Picabia. I get rid of a lot of stuff. I don’t keep any drawings. I get rid of tons of paintings. Or I’ll have them re-stretched. But my early work was cheap. I really spread it around, you know? And early on, I made all my stretchers. I had a really bare-bones operation. Like I wasn’t spending it to make it. I made hundreds of stretchers! I think about stretchers as money, you know? Having lots of stretchers makes me feel rich. Because you could do anything with these. I don’t know what to do with money, but I know what to do with stretchers.

Josh Smith’s exhibition Life is on show at Eva Presenhuber, Zürich, through 16 May 2020; a second exhibition, High As Fuck, staged on the roof of Smith’s building and consisting of paintings created during New York’s COVID-19 quarantine, is being hosted online by David Zwirner from 21 May 2020

Ross Simonini is an artist, writer and musician living in New York and California