It takes more than irreverence and a good lawyer to subvert contemporary art. The duo behind MSCHF discuss their methods

When I first mentioned to a friend (who makes her life in the media, but outside the artworld) that I was conducting an interview with some of the members of the American art collective MSCHF, she professed ignorance. But then, after a beat, she said, “Wait! They did those rubber boots… They’re my eternal enemies!” She was of course thinking of the collective’s Big Red Boots (2023), which came to dominate social-media feeds early last year by making their wearers look improbably like cartoon characters from the knees down. Her half-serious ire was directed not at MSCHF, but at the online clout-chasing that turned this particular MSCHF product into, as she so acutely diagnosed, a “whole emperor’s-new-clothes thing, but taken up by influencers”. After I directed her to the full list of MSCHF’s boundary prodding projects, she conceded that the work was “very, very funny”, and went so far as to express genuine affection for Rat Chat, a website through which members of the public could pay $3 to name the group’s pet rat, or refer ten friends and name the rat for free – a memeified lead-generation pyramid scheme.

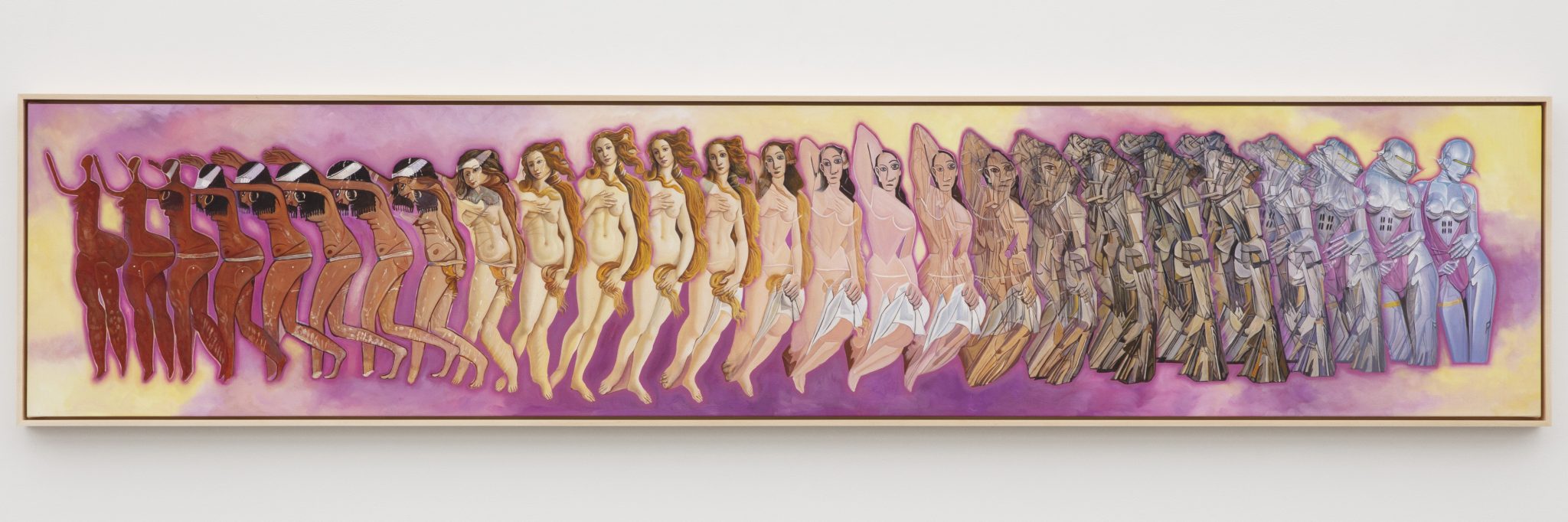

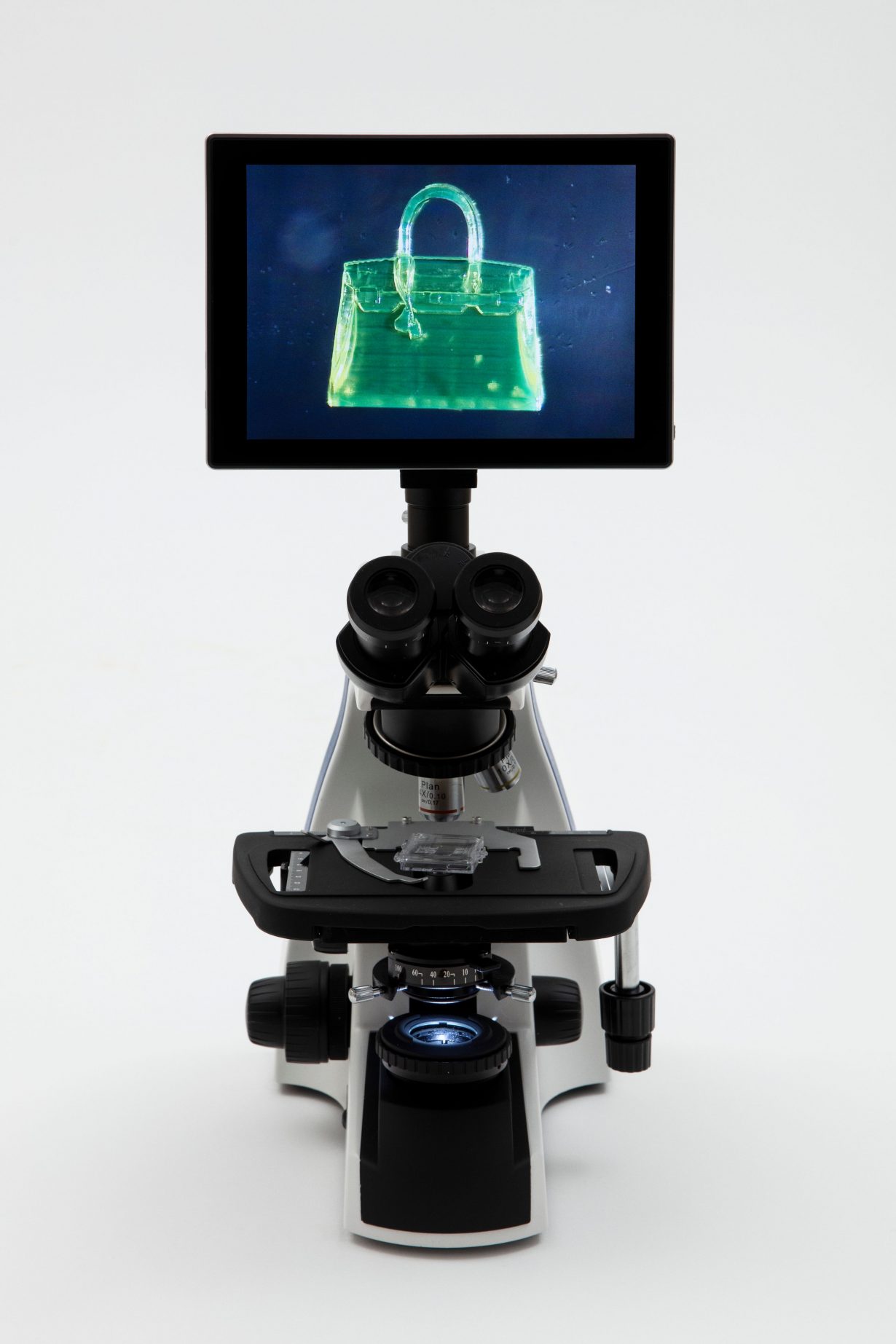

The most mischievous work in the group’s current exhibition at Perrotin (their second at a gallery, hence the title ART2) is probably Met’s Sink of Theseus (2024), a cast-resin sink whose plumbing and fixtures come from a public restroom at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where fully functional, high-fidelity copies were swapped out for the originals under the cover of an authorised repair. But the show includes everything from Candy Airpods (2024), which are just what they say they are, to a series of designer handbags (Bottega Veneta, Hermès, etc) that have been ‘knocked off ’ at microscopic scale, to paintings that depict art-historical artefacts morphing into contemporary art icons (like Muralangelo, 2024, in which Michelangelo’s David transforms in stages to Murakami’s ejaculating Lonesome Cowboy anime figure), making something like pictoral literalisations of a generative-AI prompt.

It should be clear that MSCHF takes humour seriously. If much contemporary art today is unbearably and even unsustainably earnest, then MSCHF’s projects offer an antidote, a counter-practice that exceeds the bounds of art as something far more sacrilegiously intersectional: high design, direct action and institutional critique, but also comedy and satire, lifestyle brand and ambiguous politics – all backed by venture capital, and the group’s dedication to the detail-oriented hard work of irreverence as both ethos and business model. According to its own descriptions, MSCHF endeavours to ‘challenge every sphere with which it comes into contact’. This can make an interviewer nervous. How would the ‘sphere’ of our conversation be challenged? How would the members of MSCHF with whom I was scheduled to speak, Kevin Wiesner and Lukas Bentel, both chief creative officers of the studio, cleverly subvert the conventions of our Q&A (with me surely coming out as the butt of the jokes)? Mercifully, my interlocutors proved to be candid and forthcoming – dare I say earnest – about their work. They also, in true collective fashion, began and finished each other’s thoughts and sentences, so we, in turn, make no attempt to distinguish them in the copy below.

ArtReview The jester, the trickster, the mischief maker are well codified social roles that have always existed within power structures of one sort or another. How do you think of MSCHF, to the extent that you do at all, in terms of these roles?

MSCHF There are a few words we really don’t like, one that you didn’t mention, and that is ‘prankster’. People say that about us.

AR A prank suggests that there’s a victim.

MSCHF It’s a gotcha at the end. In contrast, humour is such an important part of our work, and I think humour as a tool is incredibly powerful to get people to engage with certain subject matter that maybe they wouldn’t be able to if they were approached in a much more serious manner. A lot of that trickster sensibility that people rightly see when they look at MSCHF comes from the fact that we’re often looking for exploits and loopholes, because those are the things that you only get when there are grey areas, and that tends to be fertile ground for exploration. So, for example, with regard to copyright, it turns out that places that art history has ended up are wildly different than the places that the legal system has ended up. That tension makes it very productive to play with, and often it involves a little bit of directed antagonism.

AR How stressed out is your legal counsel?

MSCHF John Belcaster, our lawyer, is great, and he’s a really important part of the process in terms of figuring out how to thread the needle through a lot of projects. Sometimes he’s really stressed out, and sometimes maybe he should be more stressed out than he is.

AR Who are your own artistic or design heroes?

MSCHF One that is specifically connected to Perrotin is Maurizio Cattelan. From our backgrounds, Dunne & Raby and the entire speculative-design tradition were a big influence. DIS magazine and K-Hole were very important for that ambiguous quasi-business-entity-as-artist-persona, the ‘young incorporated artists’, as they were so lambasted.

AR How does cynicism play a role or show up in the studio, or in the practice? Another way to ask this would be: what are you as a studio, or individually, most cynical about?

MSCHF We have seen many instances in the past decade where satire becomes powerless. Insofar as satire has to be a recognisable absurd intensification of an existing impulse, in many places it is no longer possible to go far enough to differentiate it from sincerity. Perhaps it’s the ineffectiveness of certain creative approaches. You see a lot of artists making things that they think are doing something but it really feels like it isn’t.

AR What are the rules that dominate the artworld that you would see your work as beginning to challenge or subvert?

MSCHF There is a very ‘if you build it, they will come’ attitude to a lot of art production. But there’s a lot of value in aggressively chasing down your audience, and having as a core consideration where the work is going to go and live in the world and who’s going to see it, and not something that’s applied after the object is perfect. To design things for their ability to spread, and with consideration for where they will be seen, as opposed to just making something, putting it on Instagram and hoping someone will see it.

AR There’s a balance between virality and containment at work. The gallery and museum are containment mechanisms, physical embodiments of a kind of constraint, that has a discourse related to it, has an economy related to it. The internet, in terms of virality, lacks some of that containment. How do you think about the containment or constraint mechanisms that you are working with as a medium? Perhaps intellectual property is one kind of containment mechanism. Inside the studio, are there other things that you have identified as containers or containment issues that you are dealing with?

MSCHF Sitting with ‘virality’ for a second, people that we’ve talked to often think that we’re just chasing that all the time. For certain projects that’s not really the case. Having something go viral is never an end in and of itself. It’s a tool that you can aim towards to spread. Certain projects need a big enough audience for them to work. I’m speaking specifically about Key4All [2022, for which MSCHF sold thousands of keys that all unlocked and operated a single car, with an expectation of Grand Theft Auto-type behaviour; the result was closer to a tight-knit Discord channel come to life]. That was an idea that we had for a really, really long time, and we needed a certain number of people with a pretty uniform distribution through the 50 US states for that to work before we could even consider it. People online trying to go viral, just to go viral, will do any stupid thing to achieve that goal. As a goal it is not a good goal.

When a metric becomes a target, it stops being a good metric. When we think about working online, we’ve tried to be as off-platform as we can. Part of that is: ‘just don’t make things that are intended to live on Instagram or YouTube or even Netflix’. We have built 300 websites in the course of this practice because we want everything to live on its own terms: firstly, often purely for technical reasons, but second, just because there’s a flattening effect for everything that passes through those platforms. And, obviously, for some of the things we’re doing, you can get kicked off.

We’ve been kicked off a number of platforms. When we started, we started on Venmo, because you can send a website link, and message people with one cent and a Venmo link. It was a very effective way to get people’s attention. You’d get an email and you’d get a Venmo notification confirmation because it was a financial transaction. Eventually Venmo kicked us off. Then we moved to texting because we had everybody’s phone numbers from Venmo. And eventually we did two projects – one that was slightly a campaign-finance rule violation, and one that was slightly drug related – and then we got banned by T-Mobile.

AR What would be, do you think, the highest compliment that someone could pay your practice?

MSCHF Depends on where it’s coming from. There’s a kind of popular recognition that I think we have been chasing, which would hold up things like the Public Universal Car [2022, the collaboratively tricked-out and graffitied 2004 pt Cruiser that was the result of Key4All] or Tax Heaven 3000 [2023, an anime-influenced dating simulation that files US Federal Income taxes for free] as MSCHF’s best artworks. It’s a funny place to be, because now that we make things that go in galleries, we have a vertical of outputs that are so clearly artworks, but they’re a very small slice of the practice. I’m looking for the interactive-performance-art read of a lot of the big, overtly mass-culture swings that we’re making.

For a while people didn’t see what we were doing as an art practice. I think they couldn’t make sense of it – that was partially deliberate – but we were trying to make things in as many different verticals as possible. Many of those projects wouldn’t necessarily have been served by presenting them as artwork. That mass accessibility is held by looking like a brand or whatever in the moment.

AR In the current show, what are your personal favourite works?

MSCHF For me the sink [Met’s Sink of Theseus, 2024], and also the Botero [Ozempic (Botched Fumador de Cigarrillos), 2024, in which Fernando Botero’s bulky smoker is given a weight-reducing retouch]. The car – Public Universal Car – is also a personal favourite project. But for works made for the show, the sink was difficult to do and kind of scary. I also feel like there are very, very few other people in the world who would or could have done that particular project.

AR If you had to create an earnest motivational poster or video for the studio, what would that earnest motivational poster or video tell the people in the studio? Not ‘nothing is sacred’, right? Because obviously there are things that are sacred in the studio.

MSCHF The feedback we end up giving more than anything else when talking through things is ‘can we make it shittier?’ That goes to our ‘preserve the idea and the concept at all costs’ mentality. There is a huge attention to detail, but at the end of the day, all the decisions are designed around the question: is this keeping the core concept, the beautiful initial spark that the idea had, and presenting it as well as possible – trying to maximise its delivery, its power, its lifespan? ‘Make it shittier’ is more of just ‘simplify’, make it more approachable. It’s shorthand for a lot of things.

ART2, a solo show by MSCHF, is on view at Perrotin, Los Angeles, through 1 June

Jonathan T. D. Neil is a writer and educator based in Los Angeles