“I’m trying to be James Joyce and I’ve never passed an exam”

Northern Irish choreographer Oona Doherty’s latest work, Specky Clark – which premiered at Pavillon Noir in Aix-en-Provence last November and is currently on an extensive UK and EU tour – has been described as her most personal piece to date. “I think a producer wrote that down once when we were looking for money,” Doherty says on a Zoom call from her home in Southern France, brushing off the description with her trademark candour. “It’s one of those lines that gets picked up and repeated, but not by me. Consciously or unconsciously, all of my works are deeply personal.”

Doherty, who won the Silver Lion at the Venice Dance Biennale in 2021, has been a rising force in the European contemporary dance scene since the premiere of her seminal solo Hope Hunt and the Ascension into Lazarus in 2015. A raw exploration of working-class masculinity, the piece introduced audiences to her visceral movement style, gritty realism and distinctive use of language, where dancers seamlessly embody the rhythm of words spoken by themselves or through voiceovers. Since then, she has applied this approach to a broad range of themes, from the impact of religion on her native Belfast in Hard to Be Soft: A Belfast Prayer (2017) to the value of dance amid global turmoil in Navy Blue (2022).

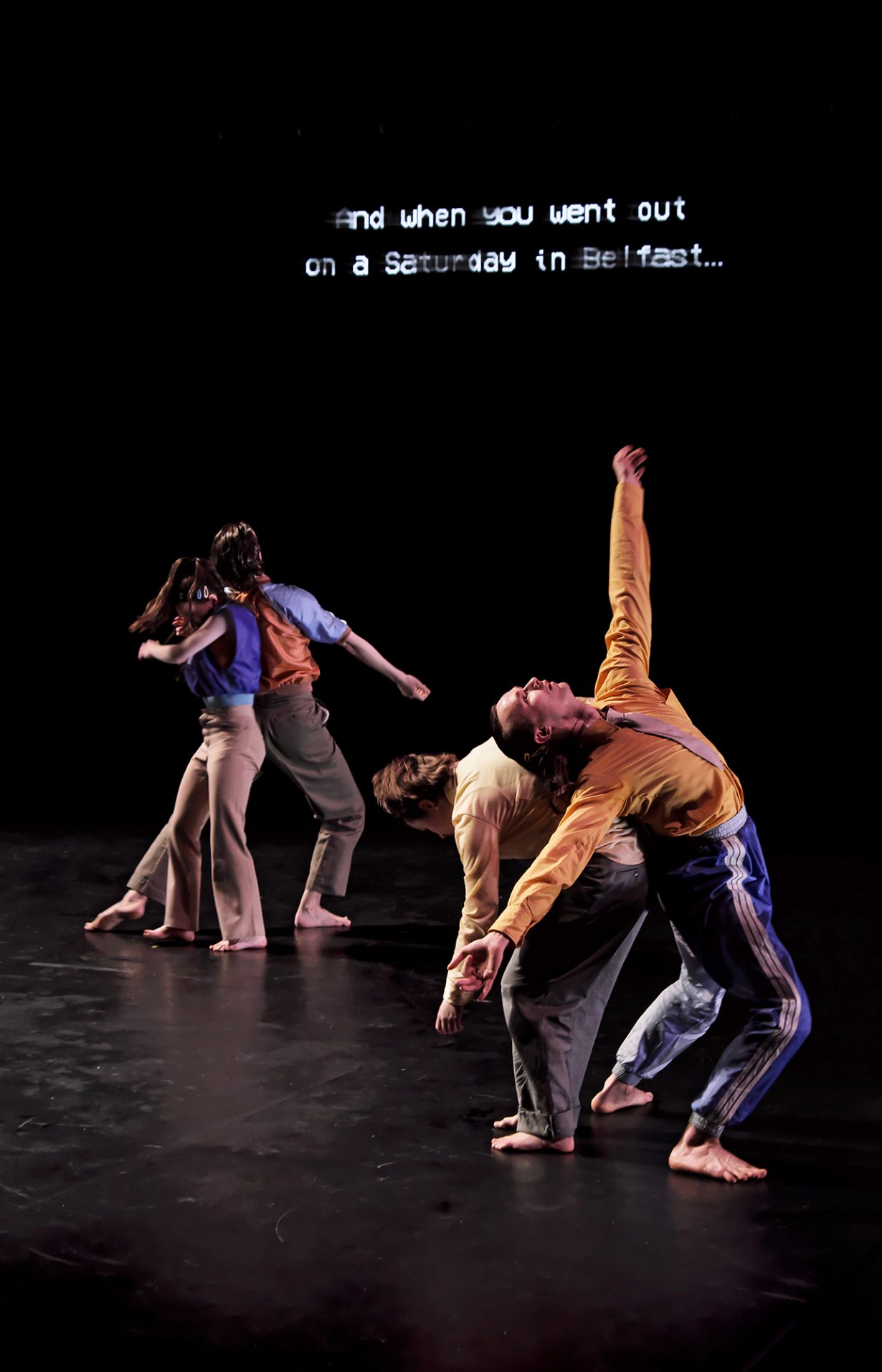

Specky Clark, however, marks an evolution in her work. Inspired by discovering her great-great-grandfather’s nickname, which now lends its title to the piece – “I thought it sounded like a fucking movie!” – Doherty originally intended to research her genealogy and write a play about her family. “There’s always been talking and words in my work, so I thought, what if I just try and do it?” she says. In the end, there’s more movement than intended, and the real family history is limited to the opening scenes. A young Specky – played by dancer Faith Prendergast in a moment of signature Doherty gender-swapping – moves from Glasgow to Belfast to stay with two aunts and work in a local abattoir. “The rest is invented, and references Irish mythology,” Doherty adds.

The result is a surreal, witty journey set on the night of Samhain, the Irish Halloween, where a slaughtered pig comes back to life and leads Specky on a quest to find the spirit of his deceased mother, peppering the journey with wry bacon-related wordplay. Along the way, they encounter a host of spirits dressed in paganlike horns and straw headdresses, who come together in a ritualistic dance to a cover of The Specials’ Ghost Town by the Irish contemporary folk band Lankum. If it all sounds a bit mad, that’s because it’s meant to be.

Becoming the Beast

ArtReview Navy Blue featured a speech nihilistically questioning the value of dance and its contribution to society. Was Specky Clark’s turn away from pure movement towards theatricality influenced by this sentiment?

Oona Doherty There’s a line in the voiceover of Navy Blue where I say, “There’s nothing left to do but mutate, eat it all alive, kickin’ and screamin’, become the beast.” I got to the point writing the speech where I was like, I have no solution. This is fucked. And I don’t even know if I have the bravery to stop and get a real job either. I am full of ego.

Navy Blue was supposed to be my last show, because I have a kid and this is fucking impossible to do [with children]. But I just fucking made another one. I made it even bigger. I spent even more money and got even worse.

AR You’re worried that it’s a waste?

OD I’ve got one voice in my head telling me, “Of course it’s not a fucking waste. Look how many really talented people get paid [because of these projects].” I just did a restaging of Hard to Be Soft, where I worked with a new group of sixteen-year-old girls for a section we call the Sugar Army. One of them wrote me a letter about how art is really important and changes people’s lives. She told me not to give up. So, on the one hand, I’m like, “You’re a dick, you should get a normal job for your kid.” On the other, I’m not harming anyone.

AR In an interview in The Gentlewoman last year, you said you need a ‘really big reason’ to make a show, and that it being ‘aesthetically beautiful is not enough’. What was your big reason for Specky?

OD I’ve always thought origin stories are fantastic, like how the Joker is a victim who becomes a perpetrator. The reason to make Specky Clark was to look at the vulnerability of sanity. It only takes three things in succession – death, bankruptcy, homelessness – and you are close to the cliff’s edge. In the show, Speck loses his mummy and then ends up in an incredibly harsh environment. It’s through no fault of the people around him. It was harsh for them growing up too.

The Irish Renaissance

AR Irish mythology heavily influenced Specky Clark. Has this always been an area of interest for you?

OD I have no interest in mythology. I keep trying to get into it, but I’m not a very good reader. I’m quite dyslexic, maybe adhd too. The only reason I’m into mythology now is through listening to The Blindboy Podcast by the Irish musician and writer Blindboy Boatclub. He made it cool for me. Blindboy was how I fell in love with Lankum too. Irish art in all its forms is having a renaissance.

AR There was a piece in Dance Magazine recently about the Irish contemporary dance boom, referencing the likes of yourself, Emma Martin and Michael Keegan-Dolan.

OD Ireland’s poppin’. Ireland’s always popped because of playwrights. The amount of fucking heavy, hardcore playwrights that have come out of Ireland is unbelievable. Maybe we’ve just been silenced for so long because of the [influence of the Catholic] Church. Now its grip is easing and art is pouring out of the scar.

AR Enda Walsh, a well-known Irish playwright, was the dramaturg for Specky Clark. What was it like working with him?

OD My original idea for the ending of Specky Clark was different. I wanted all of the creatures of Irish mythology, and anyone in Irish history that I thought was cool, to come out of the floor to meet Specky in the abattoir and have a conversation about regaining different historical important places. Then Specky would have to explain to them, “That’s a Tesco Metro now, kids. That’s a car park.” It was supposed to be a discussion about capitalism and the planet dying through the characters of Irish history.

Enda got rid of this massive dialogue scene in the end. He said we needed to twist the story to show that these things aren’t really happening, and that it’s all about Specky going mad. It really upset me for about a month, but he was so right.

AR Walsh also changed something else in the early stages of Specky Clark, right?

OD One of the original ideas was that I’d hire a lot of French dancers who would lip-sync to the Irish-accented script, and then they would stop and say in French, “C’est chaotique. I think she should have hired Irish actors.” As we progressed, Enda said, “Oona, you’ve moved to France and tried to write a play. That’s what’s funny, not what actually happens in the play.”

AR In other interviews you’ve drawn parallels between your move to France and other Irish creatives who left home only to reflect on it from afar.

OD I’m trying to be James Joyce and I’ve never passed an exam. Do you remember in the British version of The Office when David Brent wanted to write an album and go on tour? That’s me in France.

Escaping the Baggage of a Fancy Theatre

AR While Specky Clark overtly embraces the mechanisms of the theatre, you’ve also presented work in galleries. Death of a Hunter [2018–], for instance, translates narratives from several of your works into an exhibition format through film, soundscapes and an immersive crashed-car installation. What drew you to working in the visual art space?

OD The money. Fucking hell, there’s so much money. The first time I did Death of a Hunter was at the Golden Thread Gallery in Belfast in 2018. In the theatre world, you don’t get the chance to have big ideas [that span] three rooms. The [technical] proficiency that people who work in galleries have is also really satisfying. They really know how to do things well and [they] give a shit about what things look like.

We did a similar [show], but featuring more performance at Lothringer 13 Halle in Munich the following year. We got loads of smashed phones, uploaded videos onto them and stuck them to the wall. That frame suits [my work] even more than the baggage a fancy theatre brings.

AR You’ve also collaborated with high-profile visual artists: Turner Prize winner Mark Leckey created the soundtrack for The Wall, the piece you made for the UK’s National Youth Dance Company last year. It’s about the younger generation’s perceptions of today’s Britain. Why did you think Leckey was the right fit for this project?

OD Mark’s documentary Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore [1999] and his 2019 under the bridge project at the Tate – [which he asked me to dance in] – are both about Great Britain in a way… the good, the bad and the ugly. Mark totally gets that kind of shit.

When the National Youth Dance Company asked me to choreograph, at first I felt really weird. I was like, “I’m from Northern Ireland. We don’t have a National Youth Dance Company. I’m jealous.” I decided to just tell the kids how I was feeling and to ask them, “What’s great about being from Britain, and what’s really shit about being from Britain?” I gave Mark a hundred of these interviews with the kids and their grannies, as well as this song called Union, Jack by Big Audio Dynamite. I said, “Give me an hourlong track. Good luck.” He was working on five other shows at the same time, so he made a bit, and my friend Luca Truffarelli mixed the rest.

AR What was the most interesting thing that came up through the interviews?

OD I was mostly drawn to the parents’ and grannies’ opinions. From those interviews we got quotes about disappointment and lack of faith in the government. I guess that was what I was digging for, because that’s how I feel.

The main issue the younger ones mentioned was the climate, which was beautiful. But were there poor kids there? That is the question. The National Youth Dance Company is doing their very best to be able to have multiple voices in the room. But the reality is, your mum or dad has to have a car and drive you to London… to be able to do it. It’s terrible, but is [climate] the main issue [only] when you’re comfortable?

AR This year marks the tenth anniversary of Hope Hunt. While it’s now primarily performed by dancer Sati Veyrunes, you initially danced it yourself, gaining recognition for your intense, powerful delivery. Do you ever miss being onstage?

OD Maybe I regret becoming a choreographer a little bit. I love all the training before you go onstage. Not thinking about [anything else] other than “I’m going to get my leg higher” is so addictive. Sometimes I wish I’d stayed a dancer.

Oona Doherty: Specky Clark was at Sadler’s Wells, London, 9–10 May, and will be at Théâtre de la Ville, Paris, 24–27 June. Hope Hunt and the Ascension into Lazarus is also on tour, on 20 May at Théâtre Joliette, Marseille, and on 21 June at ADC Pavillon, Geneva

Emily May is a writer and editor based in Berlin

From the May 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.