“Whether they understand or not, still I’m making a conversation with them and me. I’m asking audiences to come and see and understand my history, see how everything is connected, and how even my war is also connected with everything”

Pushpakanthan Pakkiyarajah is a multidisciplinary Sri Lankan artist based in Batticaloa, Sri Lanka, whose work spans drawing, painting, video, sculpture, installation and performance. Much of his work is informed by the legacies of Sri Lanka’s Civil War (fought on broadly ethnic and religious lines between Tamils and Sinhalese, 1983–2009) in both human and nonhuman terms, and the potential healing qualities of art. Through his art he invites us to consider these issues on a more global or international scale. In particular, his work seeks to give a voice to those victims of conflict and trauma who have none. Importantly, Pakkiyarajah’s work also seeks to ask how peoples burdened with a history of conflict might deal with that while at the same time looking towards a regenerative future.

Peeling Back the Layers

ArtReview Asia When did you first become conscious of the effects of conflict on the natural environment as a subject for your work?

Pushpakanthan Pakkiyarajah The first time travelling to the University of Jaffna for my undergraduate studies, I passed through land with trees that were burnt, with no leaves. [Jaffna had been a stronghold of the rebel Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam, and the site of heavy conflict with government forces.] I didn’t know that much about art. I was drawing people – I was really good with drawing human portraits and landscapes. But being taught by [Jaffna-based artist and head of the Department of Fine Arts, University of Jaffna] T. Sanathanan prompted us to think more.

This led me to a memory of something from when I was four, when my father died. They buried the body underneath two palmyra palms. I began thinking about these two elements together, and I was drawing about my father, that particular incident. Recently, I went there again for a funeral and the palmyra are still there, still exist as island witnesses. I began thinking of other memories, like when I was in a torture camp, one or two days with my two peers. It happens because people are suspicious of people, then they’re beaten and released. It happened when I was in high school, in 2005 or 6.

Later, around 2015, I was travelling to Mullivaikkal with a bunch of artists and activists. I found a tiny, charred photo album, burned so much that you couldn’t see any images. When I opened it, it felt like I was opening some stratum or skin of some kind. It made me think of the expectations of this family who were carrying that album. I took the album back to my studio. But in the middle of the night, I started to feel it wasn’t ethical, it felt like stealing someone else’s property.

It was around then that I started to tear and burn my drawings. At that time, my studio was in Jaffna, and there were artists talks, an art archive and books, so many things happening there, a good avenue to learn and grow. Then when I got the teaching position in Eastern University, which is near Batticaloa, I came back. By that point, I was working in this way.

ARA You work across a lot of different media as well.

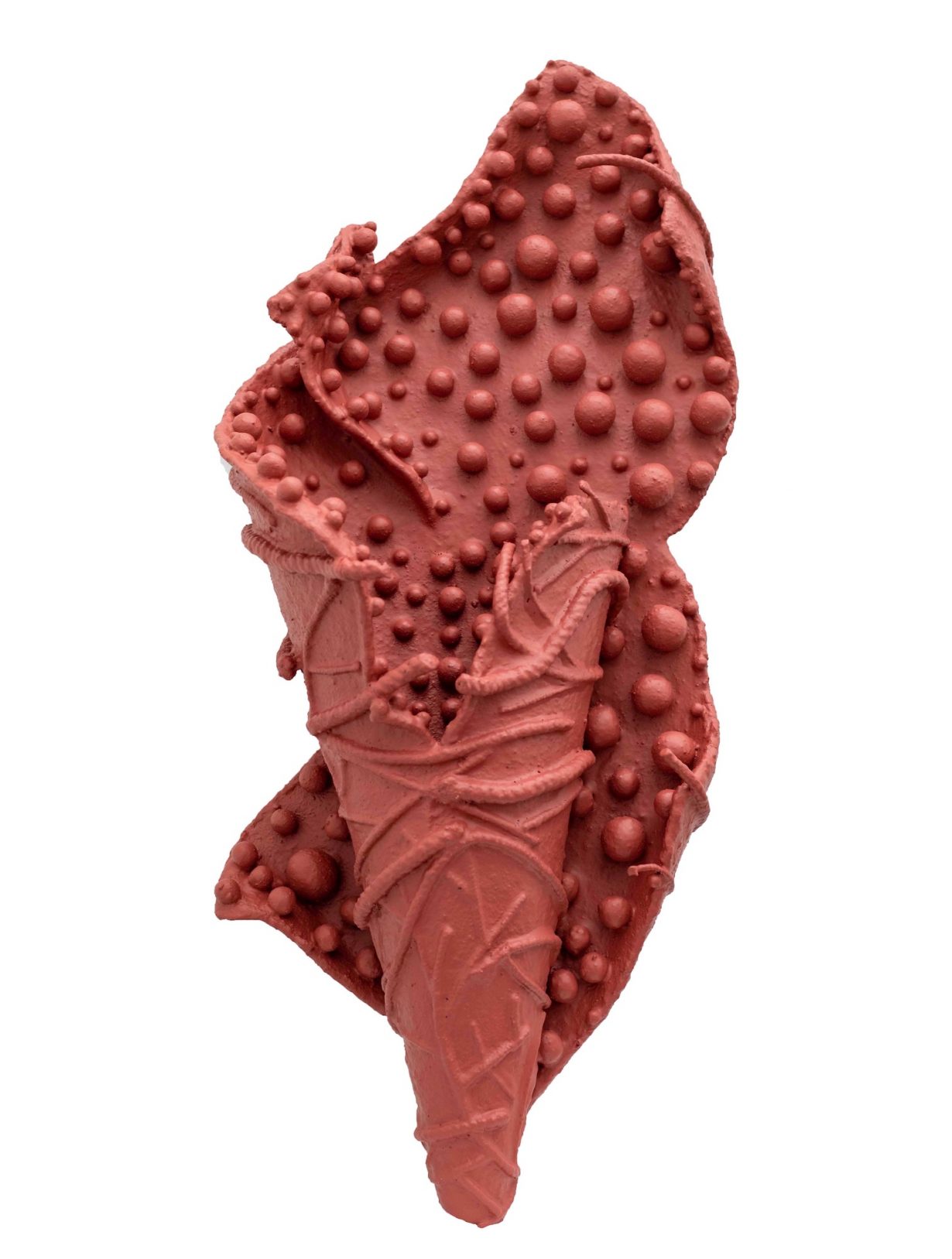

PP I’m not satisfied with any particular media. I don’t know why. I started with drawing and painting and then later sculpture, Photoshop, films and everything. Nowadays I feel like I want to touch and make something, so I’m enjoying sculpture. Where making a flower can represent an outline of fragility, or a human dead body or a tree can carry multiple representations.

Get Involved

ARA Beyond the Civil War, it also seems that the work speaks to the colonial impacts on the landscapes, and this much longer history.

PP That’s what I really wanted to portray. It’s both a portrait and a landscape, of human or nature or whichever. Already both are connected with colonial histories. Colonial drawings and images impacted my work, and how they depicted people during the conflict, how they look in front of a white person’s camera. There were several works that involved burning my own body, and work that resembled a burnt body from the war zone.

People who saw these works called them beautiful. But it made me consider how I was presenting my body as a Tamil, how they might be seeing my body and class and so on. I realised I didn’t want to present the human body in my work, especially that of my own people. My work is not about my people; it’s for everybody. But if I draw a Tamil body, it’s going to be only for Sri Lanka. How can I talk about Congo? How can I talk about Palestine? How can I talk about Lebanon, or Black Lives Matter, or anything? I want to talk about being human. I don’t want to present victims’ bodies as an object for others to appreciate.

ARA When I saw the work in Abu Dhabi, it was hard not to think of oil as well because of the black surfaces. The work is also quite open to different readings in different places; if you see it in Sri Lanka, it speaks to one thing. If you see it in the Gulf, or somewhere else, it speaks to a different thing.

PP From the beginning, I got criticised by friends and family for talking about the war, for my drawings with blood, we don’t want to see that or this. Even my mum called me one day, telling me how my drawings of screaming bodies gave her sister nightmares. I decided to shift approach, and not show blood directly. Sometimes people want to stay in their own dreamland, and they don’t want to be confronted or to be involved with anything. So I decided to shift the craftsmanship within the work, to ask audiences to travel through my complex lines of this and that, to become curious and involved, and through that to try to understand.

Whether they understand or not, still I’m making a conversation with them and me. I’m asking audiences to come and see and understand my history, see how everything is connected, and how even my war is also connected with everything. As an artist, I don’t want to think about this and that, as being isolated, as only mine. It’s ours, the conflict, everything is ours.

ARA That idea of connection is most obviously present in the Mycelium and the Charred Landscape works in particular.

PP It’s what I’m talking about talking through my visuals, talking about networks, taking mycelium and hyphae as a metaphor. It’s not only about decomposing bodies and regeneration, but also about how they are making networks. I’m inspired by a book called Forest Talk [2019], how the inhabitants of the forest speak to each other and how they support each other.

ARA Do you feel the environmental damage in Sri Lanka is continuing after the war?

PP Of course, in a different way. Economic corruption, land issues, deforestation. Elephants have started to come into our village side, and people are scared. When they complain about the elephants, I point out that humans are taking their habitats and that’s why they are coming here. My neighbours couldn’t accept it, hanging on to human-centred views. It’s not just the elephants, me and the villagers have some conflicts as well.

ARA Showing the work in a gallery, like Experimenter or in the 421 Art Campus, is a different audience to the villagers, who have a different relationship to the landscape. Maybe a quite abstract one.

PP Of course, I’m bringing my culture, sounds, the work that I produced here, that is inspired by here. As a victim, I wanted to express something. Also, it’s not that easy to express these ideas overtly here in Sri Lanka. But I also wanted to express in the work how India is also connected to the conflict; how it could be about Kashmir, about Dalit. I wanted to express how people generate conflict, and to ask who benefits from that.

But I also wanted to show this work in Sri Lanka. As an activist, and a teacher for students from all over the country, Muslim students, Hindu, Christian, everybody, I try to point out that the regionalism, the racism, the favouritism, is all engineered for the benefit of politicians and capitalists, and they need to come together to fight it. That’s why among the anti-Sufi hate on the island, I invited Sufi singing as part of the Hidden Mycelium in a Wounded Land installation.

Good Confusion

ARA As a Sri Lankan artist, do you think you’re always expected to talk about the conflict and the war?

PP Yes, as a victim of this war. People seem to get confused whether the work addresses the climate crisis or war. I feel I wanted to connect these issues; the environment can give you peace, and it’s a way in which you can heal. Often the only talk around conflicts is more human-centred, but what about the environment and land issues? War destroyed the forests, and deforestation also came from the economic corruption, which was also impacted by the war. There is no separation from this war and racism and everything.

ARA Do you also like the confusion? When I first saw the works, it wasn’t clear which thing you were talking about. It could be either, or both, or maybe neither.

PP I wanted this confusion, too, not only for the audience, but also among the political activities and the military presence here. I’m living in Sri Lanka. I want to survive. I don’t want to die. Especially in your studio, where police come with guns, asking about your work. You face something and you’re scared, so how can you remain open to everything?

ARA Have the police come around to your studio?

PP Yes, before my drawing show, The Disappearance of Disappearances [which explored the trauma of mass disappearances in Sri Lanka during the conflict] at Cornell University in 2018. I thought they were coming because of my US visa. Then friends told me, “This is not about visas. They’re just telling you they’re behind you. They’re just monitoring you. That’s what they wanted to express.” They didn’t talk about any of the work. Once they left, my landlord told me to leave the house because he thought I could be a drug dealer or something because of the many police.

More Than Just Pretty Pictures

ARA Is it harder to find spaces in Sri Lanka to show the work?

PP In Sri Lanka we don’t have that many art spaces. If you want to show, there’s temporary infrastructure, like schools with huge windows. I love that, rather than showing in huge white walls, like a white cube. Here, this is our infrastructure that we should accept, and we should respond to. It’s hard though, because art audiences are missing; people really enjoy cinema – and not even good cinema, like very commercial cinemas from Tamil Nadu – and they are happy with music, and pay to go to the theatre, but if you put on an art show and say, “It’s free, come and see”, they are still not ready to see art. They feel like art should be something else: portraits, landscapes. But they are not happy to see other words or shapes, maybe it’s tough to accept because of their experiences, and they don’t want to see that. I don’t want to force the situation, and it will take time, I think.

ARA Do you think that’s part of your job as an artist: to persuade people to come to see the work?

PP Yes. To tell them that I’m talking for them, and especially that I’m talking about them. I target my friends who come from other backgrounds or who don’t know art, and they always comment on my social media posts, “What the hell are you doing? What is this?” Once I start to explain to them and talk to them about the work, they hear it and eventually they also talk about it with the others, so slowly we can start. I think many artists are doing this, but it’ll take time for Sri Lankans to understand about art.

I can try and show that I’m bringing them, I’m bringing their story, to other people. But at the same time, I don’t believe in any records. I feel like I’m just archiving or enjoying myself or creating my own world or healing. I don’t think about impact. I want to be a silent witness about what I’m seeing or hearing. That’s it. My idea is simple.

ARA You must want to maybe change a little how people feel and see the world.

PP Of course. That happens time to time.

Pushpakanthan Pakkiyarajah’s solo exhibition No Race, No Colour is on view at Experimenter Colaba, Mumbai, 11 November – 20 December

From the Autumn 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.

Read next The fraught symbolism of Sri Lanka’s national waterlily