This year’s edition, titled Séance: Technology of the Spirit, is curated, following an international open call, by Anton Vidokle, Hallie Ayres and Lukas Brasiskis. Vidokle is an artist, filmmaker and the founder of e-flux. He has worked and exhibited in Korea numerous times, including two editions of Gwangju Biennale, where he won the Noon Award in 2016, as well as a solo show at MMCA in 2019. Hallie Ayres is a curator, researcher and art historian who has focused on the reconciliation of Indigenous and Western knowledge production, among other topics. Lukas Brasiskis is a scholar and film curator who often explores the limits and potentials of moving-image media to present more-than-human perspectives.

ArtReview How do you think what you’re doing fits in with the particular history of the Mediacity Biennale? Is it about media, as the overarching title of the biennial might suggest?

Anton Vidokle When we started working on this project, we came to Seoul and we saw the catalogue of the first edition of Mediacity Biennale, which is actually super interesting. Two things really were quite striking. One is that it was actually a very, very good show with a lot of artists who are still very relevant and very interesting today (and this was 20 years ago or more). The other is that it wasn’t necessarily a media show. There were all kinds of work. I think the initial idea was to have some media boards in the city, because at the time the municipality of Seoul had this idea to rebrand the city as a media city. Since then, this was dropped, but the biennale got stuck with the name.

AR And yet moving image and new media are the language that most people speak today.

AV I think for us this is great, because we love moving image and we’re really fascinated with moving image works, but of course this is only maybe 30–40 percent of the exhibition. The rest of it is all different genres, from painting, to performance, to music, without a particular emphasis, I think.

Hallie Ayres When we talk about media, it’s as much about mediation, and this legacy of mediation is an expanded methodology of exhibition-making – what an exhibition can or should do. Which I think is something that we definitely thought a lot about and is why we’re doing this exhibition as séance, using séance as a metaphor for this exact type of mediation.

Lukas Brasiskis ‘Séance’ is a kind of metaphor that is driving that theme of exhibition, but it is also a method. What really interested us was that séance has this history, the use of the French word is very related to the spiritualist movement in the nineteenth century, but then it became used in a different context, still with a similar logic: gathering or sitting are the origins of the word, in French.

It was not only the spiritualist attempt to speak through the medium to the dead, but it became very important for the transference of psychoanalysis, and that’s more of a connection to the subconscious realm still operating in a logical séance. Not long after that, cinema séances became very popular alongside different theatrical performances.

For us, it’s basically a kind of a connection between the present and the absent that really informs the way we thought about the artists, but also how we create the space for artworks to be exposed.

AV The word séance, the way it’s used in English, is like one thing, but actually it’s a word that’s used in many languages, including all of the Eastern European Slavic languages; French, of course, etc. It’s a peculiar word because, like Lukas was saying, it can refer to anything from an entertainment-type situation, like a theatre play, a circus performance, to psychoanalytic therapy, to post-traumatic treatment, and things like that. It’s really quite unusual. When I was growing up, you called going to a circus going to a circus séance, for example.

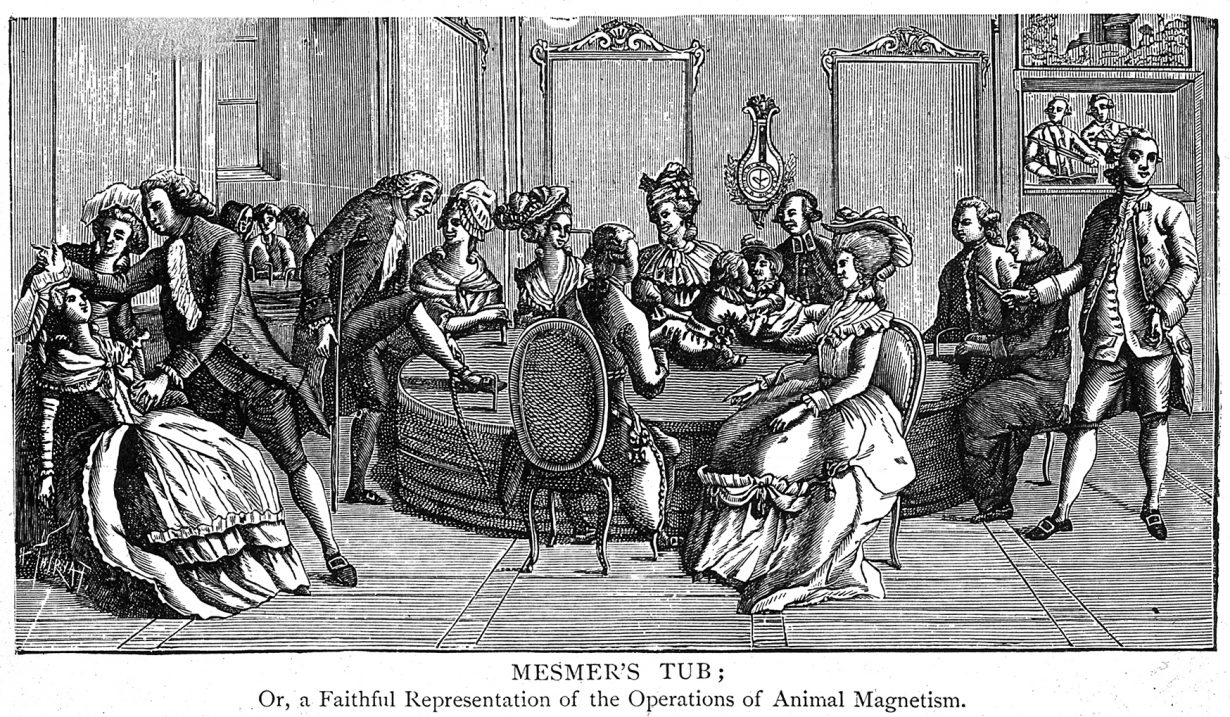

But it starts even before spiritualism. It starts with Franz Mesmer. I think these strange sessions that he was organising in Vienna with water and magnetism: for some reason, people started referring to them as séances.

Franz Anton Mesmer’s ‘animal magnetism’ sessions (later known as ‘mesmerism’) centred on the transference of energy between animate and inanimate objects. Today the techniques pioneered by Mesmer are generally known as ‘hypnosis’.

It’s really quite strange, but we like this as a model because it allows us, in the exhibition, to work with many different registers, from something that is very analytical or historical, to something that is almost dreamlike, to something that comes close to a state of trance. Somehow it permeates all of these different registers of interacting with art, let’s say.

AR Your subtitle – technology of the spirit – contains two nouns that people wouldn’t necessarily put together.

AV It’s true. Except that the word technology comes from the Greek techne, which means art. So perhaps it’s not necessarily an oxymoron or a paradox.

Yuk Hui’s ideas are very useful in this regard, in particular on cosmo-technics. The idea that there are many different technologies – as many as there are cosmologies in the world – and many different concepts of what a technology is. Through the works in the show, we’re trying to make an argument for other types of technologies that are not necessarily about an iPhone or that automatic-device type of approach, but related to other ways of being in the world.

Yuk Hui is a Hong Kong philosopher who teaches at Erasmus University, Rotterdam. Much of his work argues against universal conceptions of science and focuses on the intersection of technology, philosophy and politics. It has been particularly influential in shaping concepts such as technodiveristy and cosmotechnics, and in the emergent genre of Sinofuturism.

AR How much of that is a response to the emergence of AI?

LB In terms of what Anton said, it’s like these other alternative technologies, we consider them as nonextractive ones. It’s not necessarily a response to AI; it’s more almost about thinking outside of an extractive capitalist logic. AI, I think, is not at the moment a very big part of that logic.

Of course, it’s related to AI. This was maybe our point of departure, because a lot of ideas came from just looking at how uncannily similar historical moments are: the moment we’re living in now and the moment about a hundred years ago at the advent of modernism. Because what actually drove so many artists and intellectuals towards the occult, mystical, all sorts of syncretic religions and stuff like that, was a feeling of being oppressed or alienated by the very rapid transformation of life due to industrialisation and industrial capitalism. It was just reshaping life brutally and really rapidly along very, very rigid paths.

I think we’re living through something like this again with AI: the digitalisation of everything, algorithmic automation of everything, it produces a lot of anxiety. People feel that they will be replaced by machines, lose their jobs, etc. It’s not a surprise that we see, again, this proliferation of artistic practices that engage with the metaphysical, engage with the mystical, or the occult. I think this may be a very similar reaction, because maybe the historical moments are a little bit similar.

HA Also, at this historical moment, the advent of modernity, these kind of spiritual practices, or folk traditions, or healing remedies, or rituals were seen as the exact opposite to the modernist project. In some ways, it’s the reinvigoration of opposites, with this wave being conjectured as some sort of way out of something that’s engendered by AI.

AR You have quite a few dead artists in the exhibition. How does that work with the séance theme?

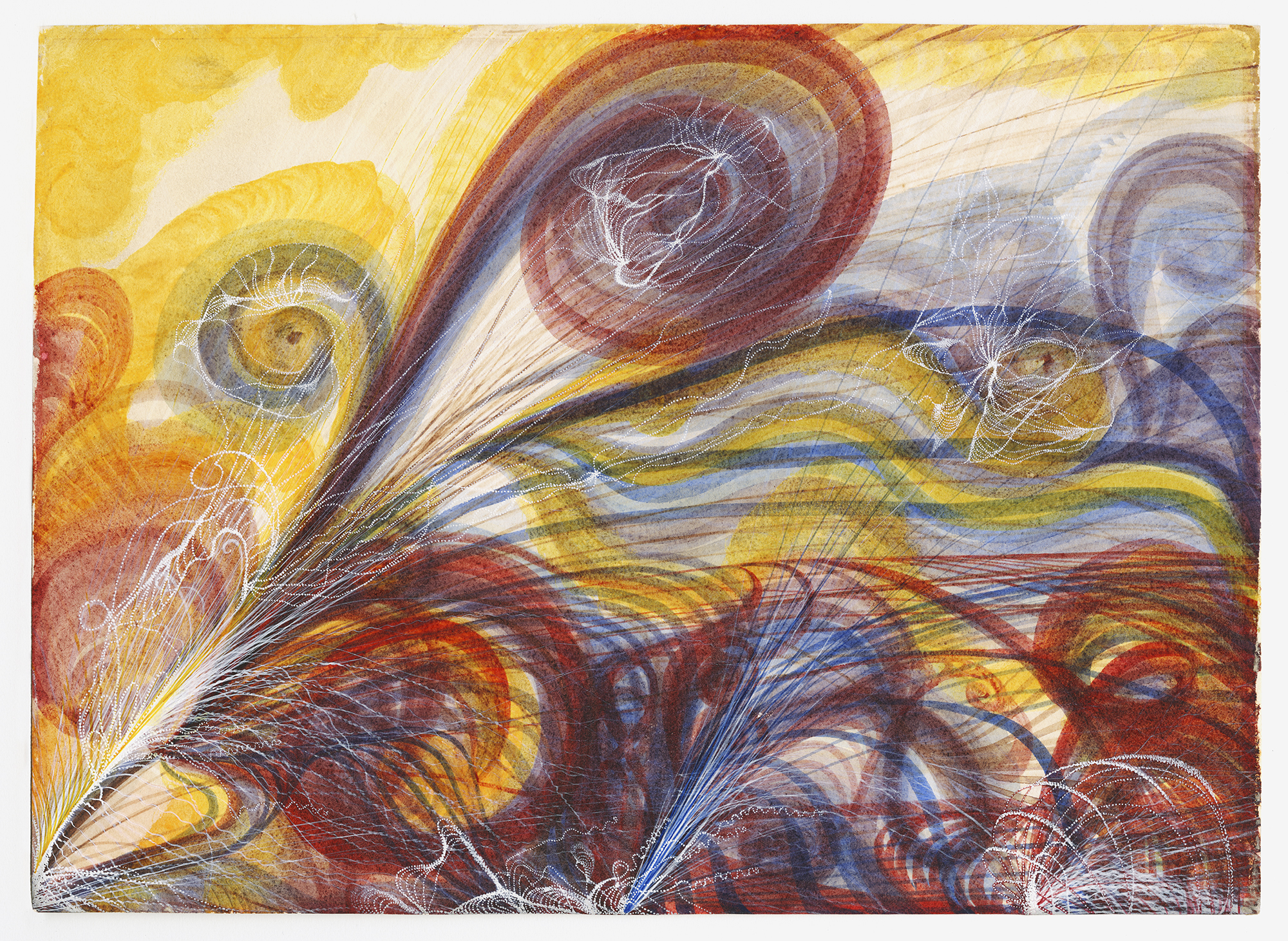

AV In a couple of different ways. Partly, it was important for us to approach this a little bit historically, just because of what we were talking about before – that we feel that we’re actually in an analogous period – so it’s very interesting to ground it or contextualise it in the first iteration of this kind of moment. We were able to get some incredible works. For me, the big discovery was Georgiana Houghton. Her work was rediscovered relatively recently – in particular there was a show at the Courtauld Gallery [in London in 2016]. She was this British woman who lived much of her life in Australia actually, but in 1861 she started making abstract paintings out the blue. It’s completely unprecedented. She could not have seen them anywhere else, because nobody would make these kind of images for another 40 or 50 years. This is 50 years before Hilma af Klint or Kandinsky or Malevich, or anything like that.

She basically said or wrote that it started with the death of her sister, who was an artist. Then she heard from some other spiritualist mediums at the time that they were putting down what they saw in their séances as works of art, as drawings, and she tried to do the same. She tried to get her sister to work through her, but that didn’t work for some reason. The sister did not want to engage in that way.

Onisaburo Deguchi cofounded the Shinto-based Oomoto religion in Japan during the 1890s . Alarmed by its subsequent popularity, Japan’s imperial government prosecuted its members under lèse-majesté laws, imprisoning members and destroying its headquarters. The religion nevertheless persists to this day.

In the end, she ended up channelling all sorts of Renaissance artists, but they didn’t make Renaissance-type work, they actually made abstract paintings. They’re incredible when you see them, because they’re made without any corrections. This is really eerie. It’s almost like the person knows exactly where every line, every colour, every stroke goes. It’s inexplicable. I’m not a religious person, and I’ve never met a ghost or anything like that, but when you see something like this, it really makes you wonder, how is this possible?

Onisaburo Deguchi is another key figure in the show. He was a Japanese mystic spiritual leader. He co-invented this religion called Oomoto, which was very, very important in Japan in the 1920s. It had a gigantic following. Then at the end of the war he suddenly made 3,000 small ceramic teacups that are incredibly beautiful and totally groundbreaking, because they go completely against the whole tradition of Raku ceramics and Japanese austerity. They look like Matisse paintings in a strange way, but this is done in 1945, when Japan was in ruins after the bombing of Hiroshima. It’s also a completely inexplicable production. Of course, this isa small part of the show, but it’s a kernel around which everything is built.

HA Thirty percent of the artists we’re showing are deceased.

AV Artists never die. Their work is there to speak for itself. You don’t even need a séance.

The 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale, Séance: Technology of the Spirit, is on show at the Seoul Museum of Art and other venues in Seoul through 23 November

This interview features in the ArtReview Korea Supplement, a special publication celebrating contemporary Korean art, supported by Korea Arts Management Service and available with the September 2025 issue of ArtReview