“I think humour is one of the very beautiful things to me”

Born in Kobe, in Hyōgo Prefecture, and having been based in Berlin for more than a decade, Shimabuku now lives in Okinawa, the smallest and least populated of the five main islands that make up Japan. His artwork, which can take on many forms and adopts an array of media, is often the product of his travels and focuses on the possibilities of communication between species and cultures. Moreover, much of his art rests on discovering the extraordinary within the ordinary, while being acutely conscious of the potential for humour within that contradiction. This first might be equated to a form of poetics; the last might be equated to a form of modesty, and often allows him to locate his work within the realm of the everyday as opposed to the privileged or segregated space of the art gallery. At the very least, his art is wonderfully and at times uncomfortably self-conscious of the latter.

Shimabuku’s work has been exhibited, since the 1990s, in galleries, museums, biennials and public spaces around the world. ArtReview Asia caught up with him on the occasion of a survey exhibition of his work, Octopus, Human, Citrus, at the Centro Botín in Santander, Spain, which was on show from the autumn of 2024 to the spring of this year. What follows is based on the conversation that took place on that occasion, but rather than a conventional interview, this is being presented as responses to various provocations and observations provided by the artist himself. Not least his suggestion that his work, and his exhibitions, feature only his own texts and writings about what he is doing and showing, so that viewers can get unfettered access to the workings of his mind. Which, in some ways, is what you would expect a conventionally formatted interview to do. Or, at least, that’s what ArtReview Asia has always assumed it’s supposed to do. And in this magazine, what it says, goes.

“I always feel like I’m making a bridge for people to go somewhere”

Eight fishtanks propped up on metal stands sit in parallel in a large room. They’re filled with clear water, the glass reflecting the diffuse daylight, while the expanse of the room’s window looks out onto a cloudy bay, as if they’re all facing longingly out to sea. Outside, large tanker ships coast by, while in each aquarium bob assorted limes. ‘Some citrus fruits float and some sink,’ Shimabuku writes for the wall text of this latest iteration of an ongoing work, Something that Floats / Something that Sinks (2024), for his exhibition at the Centro Botín, Santander, which was on view earlier this year. ‘This is something I noticed in the kitchen and found mysterious. So I decided to make work about something mysterious, and leave it mysterious, and have people experience it just as is.’ The limes generally do what the title suggests: a few perched on the glass bottom of each tank, a few nodding at the surface, while a few rogue operators float inexplicably somewhere in between. As if, you can’t help thinking, they are wilfully disobeying the artist’s commands. Or to put it more directly, as if to keep things real. Because the world at large doesn’t always behave as we wish or would like it to do. Or, for that matter, as artists would like it to do. Despite the impression given within the hermetic, shrinelike spaces that make up contemporary art galleries, designed at once to protect what’s inside and to keep out what’s without, the world is actually about relationships. And that makes it a somewhat unpredictable and necessarily unruly place, a fact that is consistently manifest within Shimabuku’s artworks.

As the citrus fruits bobble, it’s hard to tell if what you’re looking at is profound or pathetic.

“We should talk about why there is so much text in my work in the first place”

The artist himself puts this more poetically, describing that unruliness as ‘the mysterious’. You might argue that the form of his art – of playful encounter (whether it takes the form of installation, photography or video) combined with gently speculative writing – stages a space in which that can manifest. This unknown is, as he points out, something he finds in his own kitchen in Okinawa, or, as we can see in other works, something he equally finds in a packet of rubber bands, or flying a kite in the Alps, or encountering a group of snow monkeys in Texas. Moving between these places, and creating works out of his observations and unlikely obsessions, whether they concern the ordinary or the extraordinary, he comes to explore the distances between places and the translation of ideas, how chance encounters can become meaningful connections and how we might mediate and court the mysterious in our own lives.

“One reason why is that I wanted to be a poet as a teenager. I like to deal with other languages, but my mother tongue is Japanese. It’s beautiful but quite limited when it comes to having a relationship with people in the world. For that I thought that visual art would be a more direct language. This is the reason why I became a visual artist”

An artwork might result as a photograph, a video, a drawing, a sculptural display or an interactive piece; but there is always a text, which might explain the origins of the piece, or the musings that precipitated it, or even simply be the only document of an ephemeral action – as if it were part of a conceptual score and partly a laid-back liner note. The texts aren’t intended as explanatory, in the way a typical wall text might function in a museum, designed to illuminate or clarify. Or, more crudely, to tell you what to think.

“When I visited the monkey mountain in Kyoto in 1992 I heard an interesting story.

In 1972 a group of Japanese snow monkeys were brought from the mountains of Kyoto to a Texas desert. The first year, their numbers reduced dramatically. They didn’t know how to live in the desert with cactus, cougars or rattlesnakes. But in the second year their population grew. Do monkeys adapt to new environments faster than people do? I wanted to go and meet them someday.

In 2016 l finally visited them in Texas. I saw that they looked a bit Americanized, somehow. They are a bit bigger, and started to eat cactus. Now they know how to deal with the cougars and rattlesnakes. They have a new language to alert each other.

When I spent a few days with them under the Texan sun, I decided to make a mountain with ice for them. I filled a car with bags of ice. And I wondered, do they remember snow mountains?”

Wall text for The Snow Monkeys of Texas: Do snow monkeys remember snow mountains? (2016), 20 min.

“I’m not teaching. I’m not saying you have to do, or you have to read, anything. If people read my text, it’s access to my head directly. Not through people like a critic or a museum creator. I like that. I like this one-to-one relationship. They can feel freely”

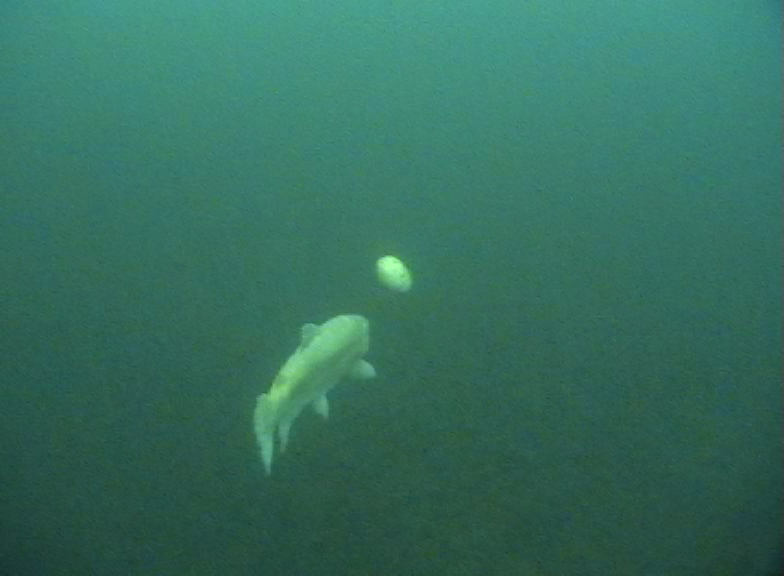

Shimabuku’s Fish & Chips (2006) is an artwork that begins as language – taking the words of the classic British seaside fare at face value – and translates the words into physical objects that then are let loose as players in a chance encounter. In the resulting short video, a potato is carried along by shallow currents, until a grey fish finds its way through the murky water, inspecting it, almost as if communicating with it. ‘Fish & Chips signs are all over the place in English towns. To me, it’s like the towns are brimming with simple and beautiful poetry. One day I wanted to make my own version of Fish & Chips. So, in Liverpool [for the 2006 edition of the Liverpool Biennial], I made a film about a potato swimming to meet a fish,’ reads the typically matter-of fact statement that accompanies the work. Thus, what is normally a greasy paper wrapper full of deep-fried food becomes instead a meditation on encountering the other.

“I’m a foreigner. That’s why I can see in that way. Maybe that’s what I’m doing: I’m trying to find the way only I, only a foreigner, could see fish and chips”

The fish staring inscrutably at the underwater potato highlights a recurring theme in his work, seen as well, for example, in an outdoor exhibition for the macaques of ‘monkey mountain’ in Kyoto, and in an underwater display of stones and coloured-glass beads for octopuses. We might be standing in a gallery, wondering what to make of his floating limes; what about other animals? The video, photography and potted cacti that make up The Snow Monkeys of Texas (2016) might document a group of snow monkeys transplanted to the desert as they curiously prod at a pile of ice that’s been left near a cactus grove – designed, perhaps, to cure them of any homesickness. But the questioning behind it is more elusive and existential. The artist observes these foreigners, who moved from Japan to the US. ‘They looked a bit Americanized, somehow,’ the wall text states laconically. ‘I decided to make a mountain with ice for them. I filled a car full of ice bags. And I wondered, do they remember snow mountains?’ Which might, on the one hand, be seen as an expression of empathy and care, and on the other as an unusual way of staging the romantic Shakespearean question: ‘What’s in a name?’

The octopus has been a multifaceted collaborator with Shimabuku for several decades, as a travelling companion, an audience for his work and a meal (though he’s clear that octopuses that are companions or audiences do not also become meals). With Octopus (1990–) is a series of texts detailing his ‘special relationship’ with octopuses – starting with an inadvertent ‘exhibition in a refrigerator’ with an old housemate who viewed the artist’s choice of food in disgusted fascination. The text and video Then, I Decided to Give a Tour of Tokyo to the Octopus from Akashi (2000) detail some of his attempts to give a tourist’s day out to a small octopus from the southwest of the country, before then returning it to the sea. The actual work is unattainable: the octopus’s memories, impressions and knowledge gained on its uncomfortable journey. Shimabuku’s exhibition at the Centro Botín gave rise to a new version of his Catching Octopus with self-made ceramic pots (2003), titled Going to meet the Octopuses in Santander (2024), a piece that arose from finding common methods of catching the cephalopods in Europe and his hometown of Kobe. A low plinth displayed dozens of artisanal examples – from small clear jars to ceramics painted with floral decorations, to elaborate hand-blown glass vessels of bright red – while a video, shot on the sandy bed of the sea outside the art centre, showed several of the creatures moving in and around the pots. The text asks a question that the video can’t really answer: ‘What kind of octopus is the octopus in Santander?’ (And, you might wonder, how is it different from the octopus in Akashi?)

In a certain way, the end product of all this is a suggestion that interspecies or geographic boundaries are really not that important. Even as the videos, actions or installations simultaneously suggest that they are.

We don’t know what happened to the octopuses caught with these pots, but in all likelihood they weren’t given a sightseeing tour of the seaside town, then returned unharmed. The exhibition was punctuated by an ‘edible sculpture’ event, the artist guiding a group through the nearby fish market to create a meal. Asked about this more consumptive aspect of his collaborations with octopuses, the artist is optimistic.

“Eating it becomes my body; the octopus becomes part of me”

This approach to material – transmutable, uneven and freewheeling – reflects the artist’s interest in cookbooks and cooking as more a model of working than as any artistic source or media. It also casts his texts as loose recipes of some form, open to adaptation and interpretation depending on who (human or not) might be preparing it. The artist likens his own way of working as being closer to a chef, “because they don’t care about which technique. They are more open, more multimedia. What they make can be served raw, can be cooked. Slow, fast. They improvise, depending on the ingredients, what they found today. When I cook, I just go to the supermarket and see things. Oh, I found a nice lamb or a nice chicken. Let’s do something with it. I like this way. I don’t care about the technique.”

Work by Shimabuku will be included in the Okayama Art Summit 2025, on view from 26 September to 24 November

From the Summer 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.