Misunderstood genius? Tick. Inspired by the muses? Tick. The formula, it seems, never grows old

Midway through Hilma (2022), Lasse Hallström’s just-released biopic of Hilma af Klint, we see the Swedish turn-of-the-century proto-abstractionist – played by the director’s daughter Tora – in her studio, painting. Or, rather, ‘painting’, since while Af Klint stands there and smiles calmly, her first abstract composition appears stroke by stroke on a canvas, unaided. In some ways it’s the sort of silly business familiar to long-term (hate-)watchers of dramas about painters’ lives – the director all but throwing up their hands and admitting that the transit between mind, eye, brush and canvas is not reducible to visual terms. And yet, to half-defend it, the conceit crystallises something about Af Klint’s mediumistic approach to painting, in which she essentially transcribed visions from the ‘spirit world’. When, shortly after, the members of her recently formed all-women artists’ group The Five see the canvas, Af Klint says: “I was holding the brush, but I didn’t paint it.”

Art biopics are also typically in the business of presenting psychological root causes, as if to compensate for all the ineffability. Accordingly, by this point in the film it’s been clarified, step by step, why Af Klint paints how she does: because of a chancy complex of life events. (Spoilers ahead for those not au fait with her life story.) First, her younger sister dies, then she loses her naval-captain father, whose seawater-soaked ghost appears to her in the night. These losses make the grief-stricken youth and nascent artist a prime candidate for the then-fashionable doctrine of spiritualism, which held that the dead aren’t really gone but, rather, remain swirling all around us. Af Klint attends seances, has visions, believes the spirits want to use her as a vessel. Meanwhile, she battles against male chauvinists at art school in Stockholm, other people call her a ‘witch’, and in her spare time she has a complicated, under-the-radar thing with the artist Anna Cassel, one of The Five. Then the Austrian spiritualist Rudolf Steiner, her hero, tells her what she’s doing isn’t art, her mother finally praises her paintings but it turns out she’s gone nearly blind, and Kandinsky gets hailed as the inventor of abstraction. Much later, after a lot of melodramatic relationship stuff onscreen, and repeated setbacks as Af Klint fails to secure both Steiner’s approval and a ‘temple’ for her paintings, she dies, having insisted her work be sealed until 20 years after her death. It took from the late 1960s to the past decade for Af Klint to be recognised as a pioneer, perhaps the pioneer, of abstract art.

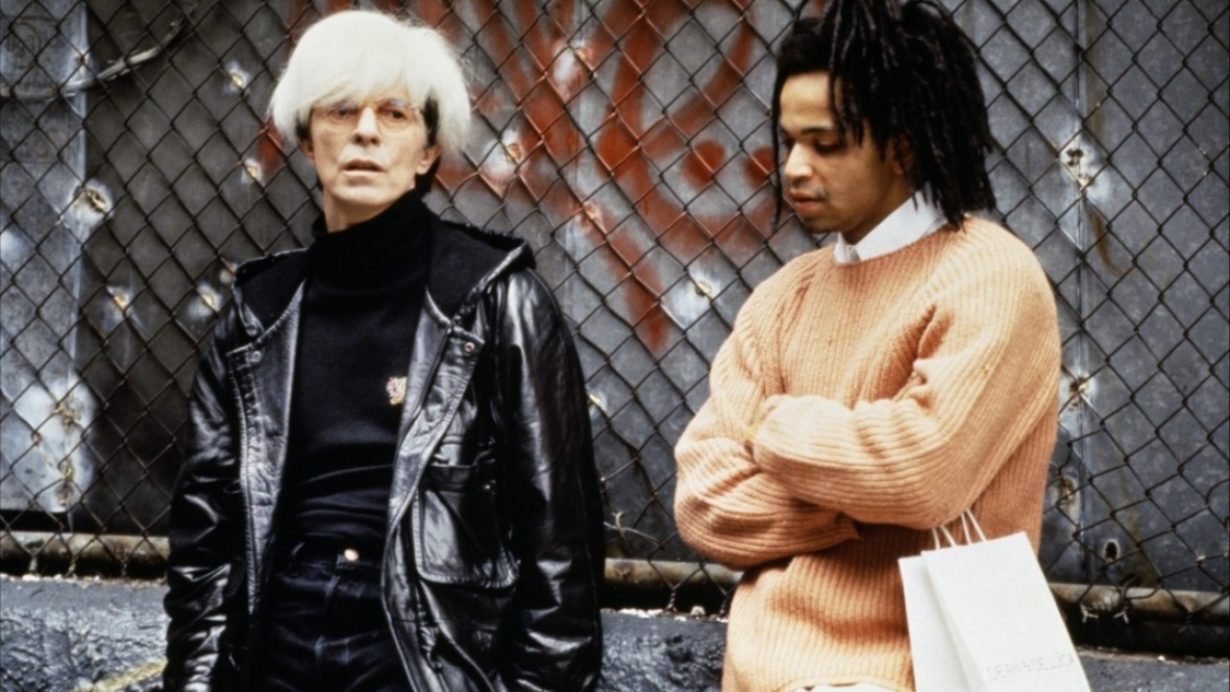

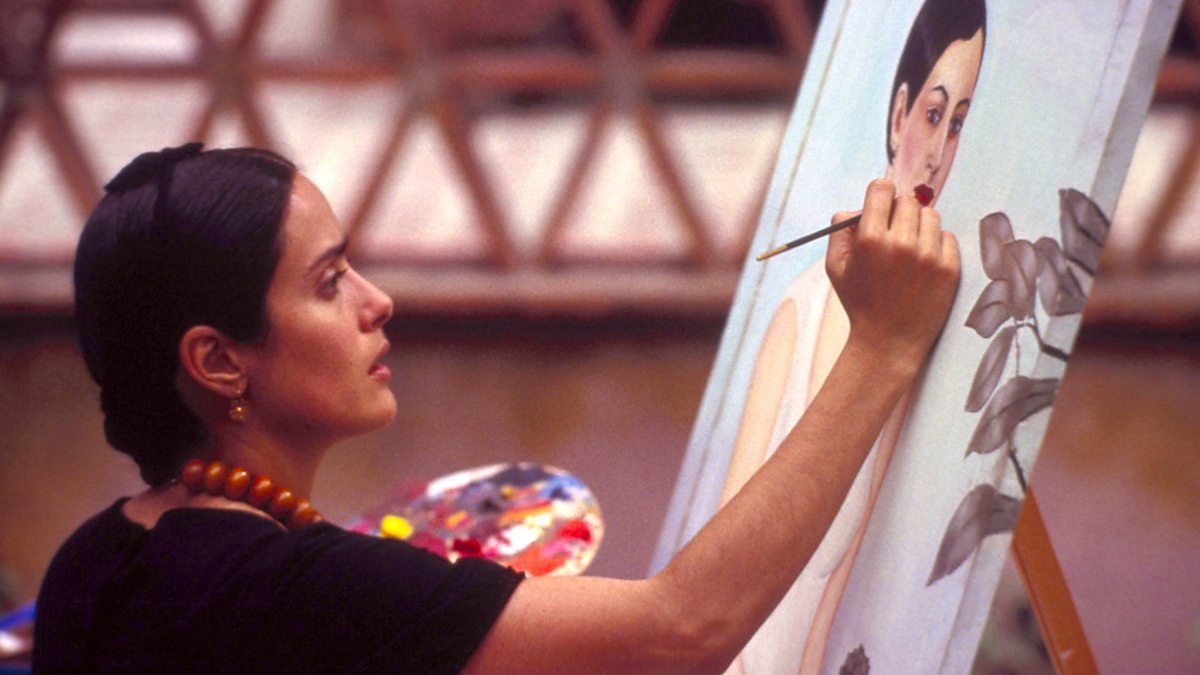

Which, if you’re versed in modern and contemporary art, you probably know, since Af Klint is firmly ensconced in the pantheon now. Hallström’s film, while movingly emphasising the hardly historical sexism inside and outside the artworld that stymied Af Klint, thus isn’t a demand for redress, though it certainly nestles comfortably within a larger moment of restitution for unfairly undervalued artists. Rather, Hilma, with its elegant cinematography, careful-looking period detailing and rounded performances, recounts a legible narrative of adversity for, one would assume, a relatively mainstream audience, and mobilises several pre-existing templates to do so. Boxes ticked: the idea of the artist as both inspired by the muses and a misunderstood genius, plus ye olde inspirational message that if you stick to your guns, especially if you’re a woman – a la Salma Hayek’s indomitable turn in Frida (2002) – people will ‘get it’ in the end (though, annoyingly, you might be long dead). This formula, it seems, never grows old; only the details and nuances change. Kirk Douglas’s scenery-chewing Van Gogh in Vincente Minnelli’s Lust for Life (1956) is tonally dissimilar from Willem Dafoe’s haunted, half-defeated, ill-fated but not suicidal painter in Julian Schnabel’s existentially spacey At Eternity’s Gate (2018), but they’re both Vincent, wrangling great art from a chaotic and cinematic life, as with Ed Harris’s Pollock (2000) or Schnabel’s earlier Basquiat (1996).

There’s little point, then, complaining that films about artists that aim for a sizeable audience prioritise lively lives, because they’re self-selecting that way. Don’t want that? The astringent inverse exists: try Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet’s second film about – or perhaps around – Cézanne, A Visit to the Louvre (2003), a sort of anti-portrait which contains no images of the French painter’s work and no images of him, focusing instead on works he saw in the Louvre and a perhaps inaccurate text, written after his death, by a confidant. The artist’s life, Straub and Huillet suggest, especially the quiet artist’s life, is not the subject for a meaningful and sincere film. Of course, a lot more people will see Hilma, and though it’s not the worst offender and will probably bring its subject to some new viewers, it does reinforce the stereotype of artists of whatever gender careening painfully through life while awaiting the next bat-signal from the muses. That’s not invariably untrue, but it’s worth remembering why most major artists’ lives don’t end up on film: because the part that’s worth looking at is already out there, in galleries and museums.