Rude, high-handed and unashamedly intellectual. Twenty years on from her death, what would the world think of Sontag today?

Always hate your heroes, that’s my advice. Then you won’t be disappointed. Susan Sontag seemed a mean piece of work. She has been described as a quintessential New Yorker, and that seems about right: the embodiment of all that is narcissistic, venal and self-aggrandising in that most inwardly fragile of cities. ‘Unflaggingly rude to waiters, cab drivers, hotel clerks,’ was Gary Indiana’s recollection of his fellow downtown denizen in I Can Give You Anything But Love (2015), someone who thought being on time was ‘servile’. The novelist Sigrid Nunez – her live-in secretary and then-partner of her son – described Sontag as ‘a feminist who found most women wanting’. ‘A bullying monster’, thought Salman Rushdie in his memoir Joseph Anton (2012). There’s a widely circulated meme, first produced by satire blog ClickHole, about the moment when the worst person you know makes a great point. But what about when a bully produces one of the best works of art you know? Or when someone whose personal abrasion you’d probably find abhorrent writes books you keep dear, dog-eared and close at all times, precisely because of the combative spirit and force of argument on the page? Sontag would be ninety-one this year – she died twenty years ago this past December – and I wonder what she would have thought about the world today, and in turn what the world would have thought of her, were she still around. My gut feeling would be mutual suspicion.

Sontag was born into a nonobservant Jewish family in New York City in 1933. Her father died of tuberculosis when she was five; her mother was drunk most of the time, and Susan hated her. Adopting her stepfather’s surname, Sontag moved around the US, from school to school; hiding out in the library, books staving off loneliness. She would go on to study philosophy through to a doctorate from Harvard. In 1956 she dislocated herself from the academic treadmill and moved back to New York, where she would live for the rest of her life. Sontag became a cause célèbre among the city’s literary elite in 1964 upon publication of her ‘Notes on “Camp”’ in Partisan Review, then the go-to organ of America’s liberal intelligentsia. The text was a provocation that popular culture should be treated seriously – a love letter to ‘artifice and exaggeration’, as Sontag put it – which amounted to an attack on the old guard that still dominated the publishing houses and museums of America. The fact an art critic can today reference something as facile as an online meme, in the introductory lines to an article on a philosopher, is in a large part down to Sontag. Critic Hilton Kramer bemoaned what he saw as Sontag’s severing of ‘the link between high culture and high seriousness that had been a fundamental tenet of the modernist ethos’. Sontag countered: ‘If I had to choose between The Doors and Dostoyevsky, then – of course – I’d choose Dostoyevsky. But do I have to choose?’

Camp, for Sontag, was to revel in a mask or a style and to be ‘disengaged, depoliticized’. Just as camp at its best contains a kind of monstrous frivolity, so it was monstrousness that drove Sontag. Perhaps the fact she wasn’t a nice person was where her genius lay; a position at odds with today’s desire for ethical purity. She herself saw this, believing: ‘The bigots, the hysterics, the destroyers of the self – these are the writers who bear witness to the fearful polite time in which we live… writers such as Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Dostoyevsky, Kafka, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Genet – and Simone Weil – have their authority with us precisely because of their air of unhealthiness. Their unhealthiness is their soundness, and is what carries conviction.’ Add the author of those words to that list.

Benjamin Moser, in his hefty, elegiac 2019 biography of Sontag (which won the Pulitzer), records the explosion of the Sontag name among the intellectual elite of New York, along with all the quarrels and jealousy that comes baked into that calibre of fame. Sontag seemed to relish it, indeed any shade of argument (she’d have skewered #bekind sentimentality). It is entirely in keeping with her personality that having been praised as the leading new voice in aesthetics, she followed ‘Notes on “Camp”’ with the book of essays Against Interpretation just two years later (a collection that included the former). ‘What is needed, first, is more attention to form in art,’ she declared. ‘If excessive stress on content provokes the arrogance of interpretation, more extended and more thorough descriptions of form would silence. What is needed is a vocabulary – a descriptive, rather than prescriptive, vocabulary – for forms.’

While Sontag felt the need to rally against the deadening hand of interpretation, in which a blanket of projected meaning suffocates the original artwork, sixty years later the artwork faces a different killer: the image of its maker. Today a painting or sculpture has been reduced to an avatar of its author, and their identity or biographical baggage, or at least an avatar of what a curator or critic wishes its author to be. Even in writing Illness as Metaphor (1978), she never once references her own cancer diagnosis three years earlier. ‘I’m anti-autobiographical,’ she would tell friends, in stark contrast to the cultural narcissism of autofiction of the present: for Sontag, her life provided the subject matter, but she did not need to be the subject. Her medical treatment was never discussed in print, nor were other matters, such as her sexuality, yet her writing remains personal and reflective and lived. A lesson for today’s obsession with the first-person I… I… My…, however meagre the story.

In 1970 Sontag was part of a trip facilitated by the North Vietnamese government for US antiwar activists and writers. The resulting report for Esquire is a bland picture of Hanoi, filtered through the prism of US left-right political discourse, as opposed to a portrait of a real country in that moment. Nonetheless, it had a transformative effect on the writer, evident in her work thereafter. Sontag recognised that war, and the experience of society in its most perilous form, could be the monstrous foil to art, far removed from New York’s bohemia. On Photography (1977) was her next landmark work to follow her visit to Vietnam, in which she notes the tight embrace between pain and art. She questions the political purpose of the camera (‘photographing is essentially an act of non-intervention’) and sees the lens symptomatic of a life lived at one remove. ‘War and photography now seem inseparable, and plane crashes and other horrific accidents always attract people with cameras,’ she writes. ‘A society which makes it normative to aspire never to experience privation, failure, misery, pain, dread disease, and in which death itself is regarded not as natural and inevitable but as a cruel, unmerited disaster, creates a tremendous curiosity about these events – a curiosity that is partly satisfied through picture-taking.’ For her, the question of the ‘Western gaze’, or the privileged subject, merited diagnostic interrogation, but the antidote was not isolation.

Illness as Metaphor (essentially Against Interpretation repurposed for sickness), published just one year later, is yet another appeal to embrace the grit of life beyond mediation, and intellectually dissect the agony of it; to pull away from the deadening hand of aesthetics and linguistic obscuration: ‘Nothing is more punitive than to give a disease a meaning – that meaning being invariably a moralistic one. In the name of the disease (that is, using it as a metaphor), that horror is imposed on other things,’ she wrote in the book’s most famous lines.

Sontag first went to Sarajevo in 1993, at the invitation of PEN International, a year into the Bosnian war and the siege of the city by Serbian troops (when the ‘mountains surrounding the city became our worst enemies’, as one journalist recalled). Here was a place in which art could only exist – could barely survive – in its rawest form, stripped of the ritualised theatre that surrounded culture back home in Sontag’s New York. The trip affected Sontag deeply, but it was not her idea to produce a play amid the conflict. That came from Haris Pašović, the director of the MESS international theatre festival in Bosnia, to whom she had been introduced and who faxed her on her return to New York challenging her to come back to Sarajevo and ‘make a real piece of art’. ‘While you make the fog the real life and the real death are happening here,’ he wrote. ‘Move your fucking asses and make something real.’

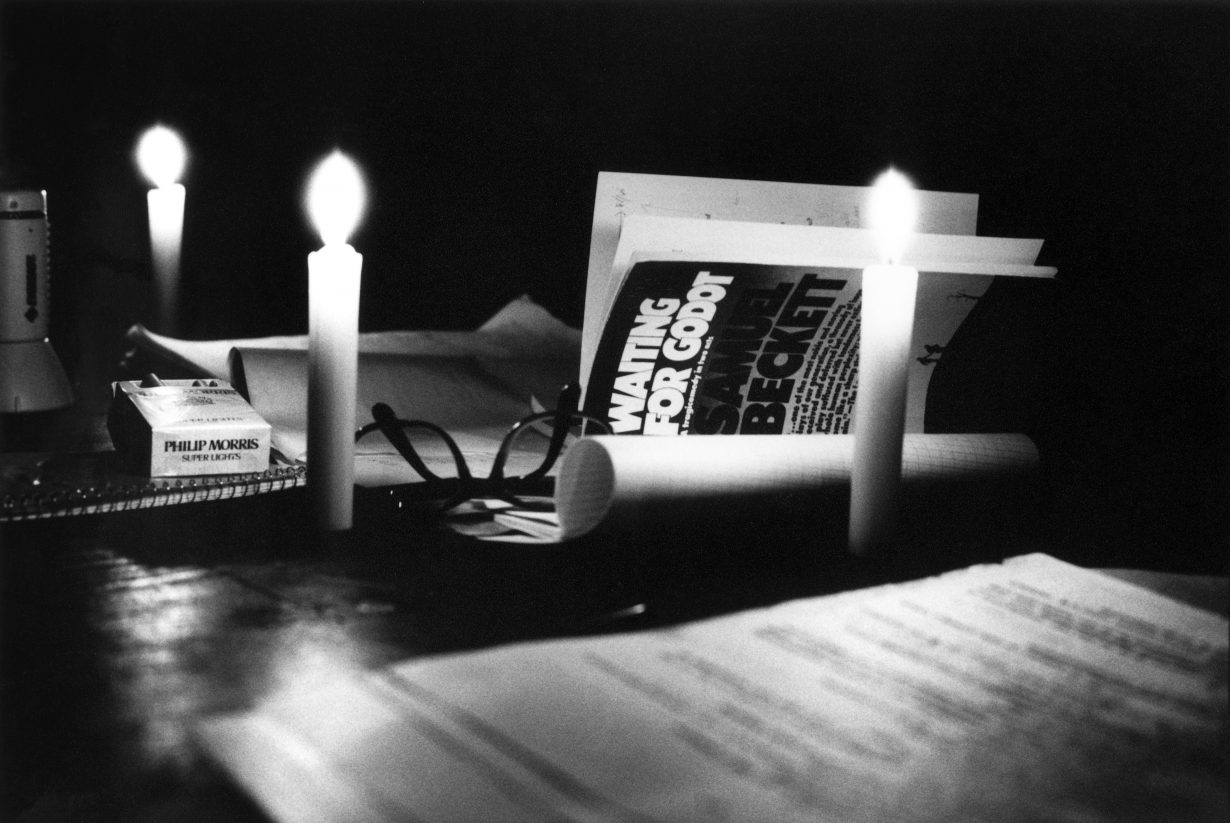

A battle against the fog – interpretation, metaphor – was Sontag’s lifelong project. She could not refuse the invitation. She arrived in Bosnia with great wads of Deutsche Marks hidden in her clothes, the wages for the actors and technicians she would employ to stage Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (1953). No production of that play has an elaborate set, but Sontag’s must be one of the starkest, the only stage furniture being the plastic sheets the UN provided to cover windows from the view of snipers. Moser writes how Beckett’s Vladimir and Estragon are ‘waiting for a salvation, a climax that never comes. In Paris, in 1953, these were artistic choices: metaphors. In Sarajevo, forty years later, they were daily reality.’

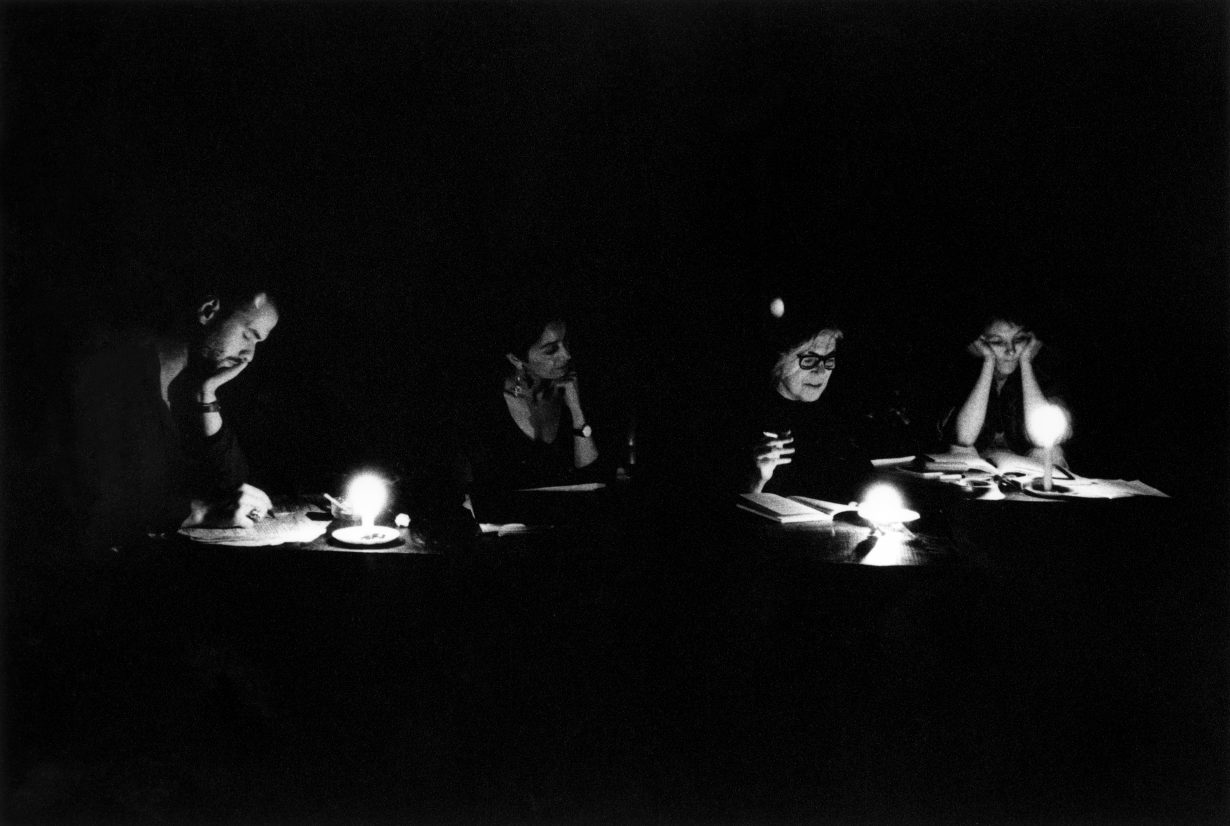

Sontag halved the play to just its first act, as if the second part must wait until after the apocalyptic context of its staging had passed. The two characters were expanded into three couples: a man and a man, a woman and a woman, and a man and a woman. Every Bosnian, waiting to be saved. We can expand this in our mind today: every Palestinian, every Sudanese, waiting to be saved, waiting for some humanity. The UN’s largest life-saving airlift in history had not yet begun; the Bosnian actors, starved, were slow in learning their lines. Being able to light the stage only by candle meant that the original directions were hard to replicate; the details of the performance were circulated only by word of mouth (a few months earlier an exhibition of political cartoons had been announced in the newspaper, and at the exact time of the opening Serbian shells came from the hilltops into the gallery). Despite such desperate circumstances – and indeed because of such desperate circumstances – Sontag’s Godot was a triumph, inducing tears in its immediate audience, lauded as a climax to her career by those beyond the siege.

It was art at its most visceral, an intellectualised horror; a culmination of Sontag’s vision in which Beckett’s words are stripped of artifice and put to work amid human depravity and a civilisation in near-ruin. It was unashamedly intellectual, a difficult proposition; beautifully immoral even. The antithesis of cultural sensitivity. ‘Someone who is perennially surprised that depravity exists,’ she wrote a decade later in Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), a year before she eventually succumbed to cancer, ‘who continues to feel disillusioned (even incredulous) when confronted with evidence of what humans are capable of inflicting in the way of gruesome, hands-on cruelties upon other humans, has not reached moral or psychological adulthood.’ Sontag revelled in the monstrous, but lived a grown-up life in which she sought to shed the comfort blanket of mediation; a life lived unafraid of criticism.