In Man and Beast at the Royal Academy, London, the uncanny overlapping of familiar and strange is a psychic reminder of our animalness, provoking horror more than genetic discourse

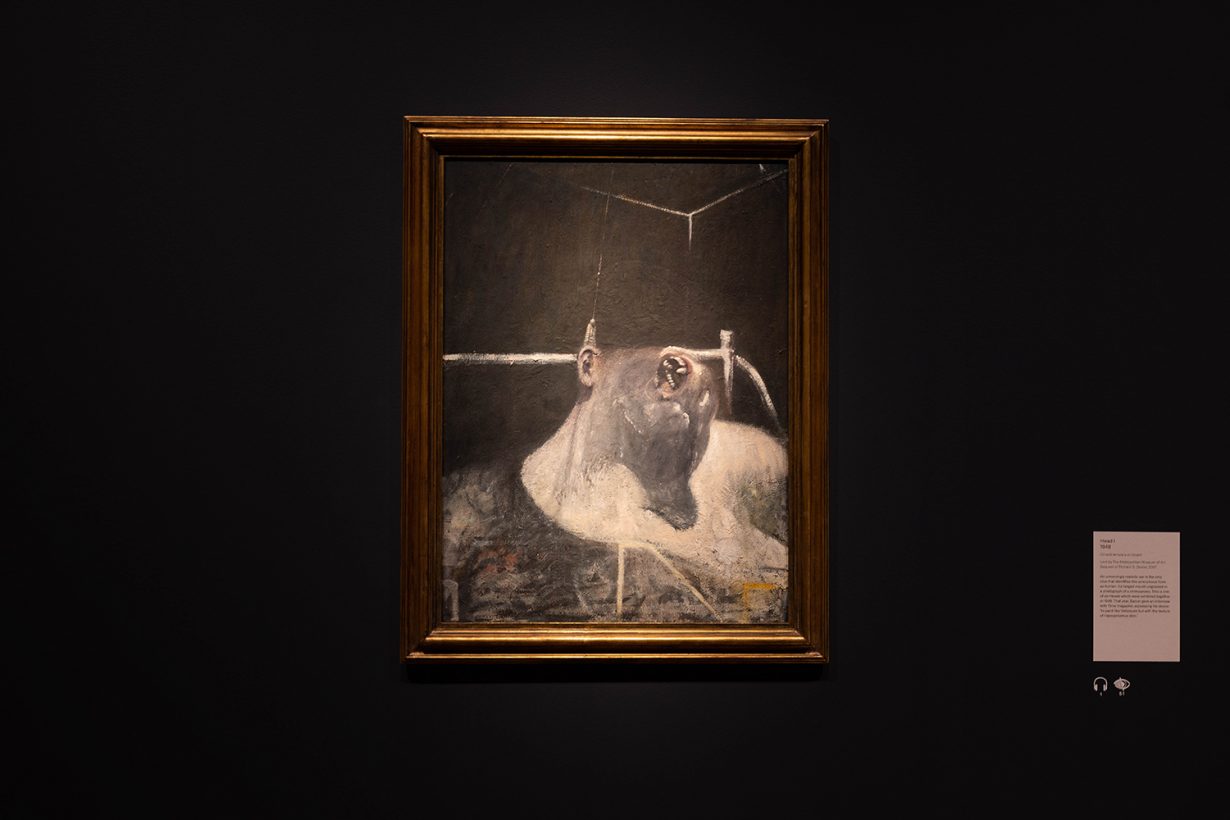

A fresh curatorial premise can renew our experience of an artist’s work, which is especially welcome with an artist as iconic and mythically familiar as Francis Bacon. Curator Michael Peppiatt does this by homing in on the images of animals in his work, stating that Bacon ‘sensed how closely man and animal would interact, whether caged or uncaged, to the point where each depends on the other to survive’. This statement feels forced, its ecological rhetoric ill-matched to Bacon’s nightmarish, often fantastical creatures, which defy taxonomy by being germane first and foremost to the paint. Head I (1948), shown by itself in the opening room, both refuses and struggles to be, its only anatomical elements being a human ear and a chimpanzee’s mouth, locked in a contortion of existential agony. It is less of a literal interaction between human and chimpanzee, or their respective orifices, than a nightmare born of the painter’s skill in suspending resolution. We are left hanging, as though subjected to some Hadean punishment, which along with Bacon’s hard-to-match virtuosity has its own morbid pleasure.

Despite Bacon’s evident interest in animals – stemming from his father’s profession as a racehorse trainer, the story goes – the human presence always predominates, animals coming second to the anthropocentric endeavour of art and image-making. Wildlife magazines and Eadweard Muybridge’s time-lapse photography were the mediated form of much of Bacon’s engagement with the animalistic. In Dog (1952) and Man with Dog (1953) Bacon experimented with a single image captured by Muybridge, repeating it as compositional device to varied effects. In the former the dog functions as a kind of energetic motor, bringing antagonism to the otherwise serene, almost sterile composition. In the latter it partakes in an experiment in tonality, fighting to prevent the image from disappearing into blurry nonexistence, while somehow speaking to the shadowy human legs behind it in a semiabstract tableau of urban, masculine loneliness.

The physiognomic, scrambled portraits and studies of the human body remind us of animality’s relationship with the well-established Baconesque tropes of carnality and mortality. Two Studies from the Human Body (1974–75) look almost like apes in a zoo, but they are hardly zoological; the uncanny overlapping of familiar and strange is a psychic reminder of our animalness, provoking horror more than genetic discourse. The picture is funny, too. Putting a baboonish head on an athletic, all but classically proportioned body, with jets of semenlike paint shooting from the buttocks of the figure upstage, it pokes fun at humanity’s civilised pretensions. Indeed, there is a touch of the camp in Bacon’s pink outline of an ape in ‘Pope and Chimpanzee’ (c. 1960), which he could have drawn from one of Charles Darwin’s diagrams, as if to mock the scientific establishment as well as the religious.

Many of the works reek of sex, the aesthetic tension between pain and pleasure, violence and grace, suggestive of Bacon’s sadomasochistic predilections. Although his sexuality is touched upon – with reference to his overtly homoerotic Two Figures (1953) and Two Figures in the Grass (1954) – more could have been made of it (he did claim, after all, that he found the smell of horse dung ‘sexually alluring’). Bacon was openly gay when it was illegal to be so, for which reason this element of his life and work was wilfully overlooked in earlier criticism. By giving what feels like perfunctory attention to the issue, the exhibition tends to perpetuate this oversight.

Most of all, the show inadvertently reveals the futility of trying to taxonomise the subjects of Bacon’s work in any literal sense. It exemplifies the dangers of uncritically aligning eco-theory with artistic intention; the wall text often quotes from Bacon himself, without once considering his rampant tendency to self-mythologise. One of the highlights here is the appearance all three of his bullfight studies (all 1969) in a single room for the first time. But more than ‘challenging a clear distinction between human and animal’, as the wall text argues, surely the noteworthy union here is the marriage between the subject matter and Bacon’s ability to choreograph ineffable formulations of elegance and machismo, movement, poise and stillness in paint. The distinctions are unclear, but they are felt, they are there – it’s just we don’t know how he puts it all together. In Bacon’s world, we are all paint.

Francis Bacon: Man and Beast is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, until 17 April