In apartheid South Africa, museums glorified white settlement and erased Black history; in the US today, they are again being captured under the guise of neutrality

What does it look like when a government seizes control of museums? In apartheid South Africa, the answer was at once banal and brutal: sanitised dioramas of ‘tribal life’, heroic murals of white pioneers and a list of national monuments that treated settler battlefields as sacred while erasing the histories of the Indigenous majority.

Today, in Donald Trump’s America, we are witnessing something chillingly familiar. The executive order targeting the Smithsonian and Trump’s self-appointment as chairman of the Kennedy Center are not just acts of symbolic politics. They are part of a deeper authoritarian logic, one that seeks to purify public culture by narrowing who gets to tell the story of the nation.

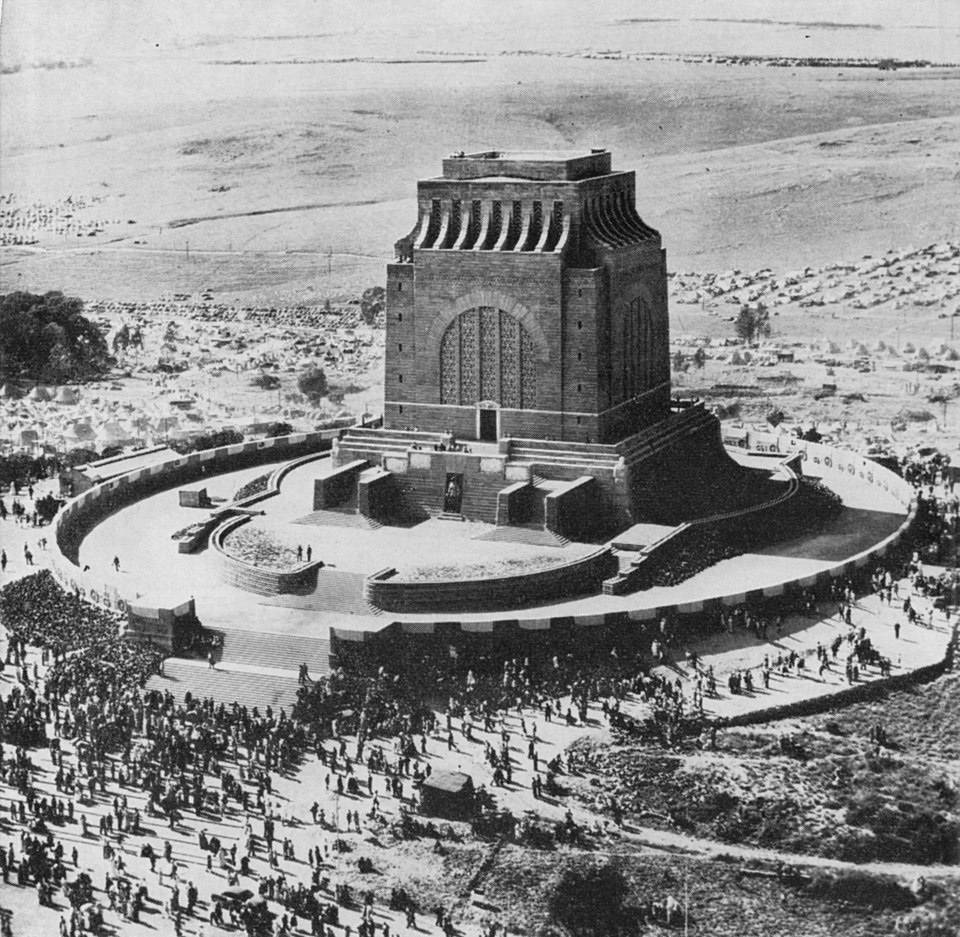

From the 1950s onward, apartheid South Africa built a vast cultural machinery to shore up its racial order. Museums were curated sites of propaganda. Overseen by the Department of National Education and ideologically steered by Afrikaner networks like the Broederbond, these institutions advanced a vision of history in which European settlement marked the start of civilisation and African life was reduced to folklore, fauna or anthropology. The Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria, inaugurated in 1949, cast white settlers as Christian heroes fleeing British tyranny, sanctifying their conquests in stone and murals. Its massive, fortresslike design broke sharply with the Cape Dutch revival and eclectic colonial styles that characterised much of South African public architecture at the time. Instead it embraced a monumental nationalism: severe, geometric and imposing, designed to project permanence and materialise a racial mythology in granite. For Afrikaners, it symbolised destiny; for Black South Africans, exclusion.

Meanwhile, in Cape Town the South African Museum (established in 1825) featured glass-encased dioramas of San and Khoekhoe figures posed in stylised and static ‘ethnographic’ scenes. These displays treated African people not as historical agents but as anthropological types, suspended outside time. Exhibits on resistance, urban life or modern Black thought were absent. As Patricia Davison, a South African curator and anthropologist, put it in 1991, ‘the design of the gallery lent credibility to the questionable idea of bounded ethnic groupings and reinforced an ideology of cultural difference’. The exhibition framed whiteness as dynamic and civilisational; Blackness as stagnant and premodern. Together, these institutions trained the public to see racial hierarchy as natural, even benevolent, as they furthered the false notion of the colonisers as saviours in the face of indigeneity. They made apartheid’s ideological order visible – and in doing so, they helped secure it.

By the 1960s, this ideological grip extended to institutional structure itself. The 1964 creation of the South African Cultural History Museum (today part of the Iziko Museums group) was not an administrative reshuffle but a politically engineered act. Led by National Party functionaries and members of the Afrikaner Broederbond, the museum was designed to celebrate European material culture and reinforce white South African ‘heritage’. African life, by contrast, was cordoned off into natural history. Even the architecture of knowledge (who belonged to ‘culture’, who to ‘nature’) was shaped by apartheid.

Yet even under the weight of this machinery, resistance endured. During the 1980s, artists and cultural workers – especially those aligned with the Black Consciousness Movement – began building a counter-archive. Institutions like the Federated Union of Black Artists, township art centres and radical theatre spaces nurtured forms of cultural memory that defied state control. These were not museums in the conventional sense. But they preserved what official institutions sought to erase: Black futurity, struggle and the right to narrate one’s own history.

This is not to equate the United States today with apartheid South Africa. The contexts and conditions differ profoundly. Apartheid was a codified system of racial domination, enforced by law and violence. But authoritarianism, wherever it emerges, tends to follow familiar scripts. It seizes culture first. Museums, curricula and monuments become tools for narrowing national identity, for flattening history into myth, for dividing who gets to belong and who must be erased. What apartheid made explicit – through legislation, monumental architecture and the staged absence of the Black majority – Trumpism approaches through the rhetoric of neutrality and the bureaucratic purge. The forms differ. The logic rhymes.

After apartheid’s fall, South Africa’s museums were tasked with reinventing themselves for a democratic era. Some institutions, like those folded into the Iziko group, reoriented their mandates, curating new exhibitions on slavery, resistance and everyday Black life. Others, like the Voortrekker Monument, were left intact but recast – linked to places like Freedom Park in an attempt to narrate a pluralistic national story.

Yet beneath these gestures, deeper continuities persisted. Budgets favored flagship institutions over community museums. Epistemologies rooted in Eurocentrism lingered. The representational shift was not matched by structural redistribution of land, of funding, or of authority. In time, these gaps produced disillusionment. Institutions that once promised transformation came to feel hollow, rehearsing reconciliation while inequality deepened. They became vulnerable not because they went too far, but because they didn’t go far enough.

This logic – the use of cultural institutions to legitimise power – resurfaces, in different form, in the United States today. In March 2025 Trump issued an executive order accusing the Smithsonian Institution of promoting ‘race-centered ideology’ – a phrase designed to cast antiracism as divisive, even un-American. The order suspended DEI-related programming and placed diversity officers on indefinite leave. Days later, Trump dismissed the Kennedy Center’s board and appointed himself chairman. These moves were framed as efforts to restore objectivity. But they are best understood as the authoritarian appropriation of culture.

Trump’s attack is not just on particular policies or personnel. It targets a broader ideological framework – one that treats history as contested terrain. In its place, he proposes a sanitised vision of national heritage, rooted in biological essentialism and cultural nostalgia. Museums and arts institutions are to be returned to a prelapsarian neutrality, where whiteness is unmarked and dissent is disorder.

This is not new. Authoritarian regimes have long recognised that controlling the cultural field is key to shaping the political one. Museums are not just about the past; they define what – and who – belongs in the present. And when institutions falter in their ability to transform substantively, they become easy targets. What begins as a complaint about DEI becomes a broader purge of critical memory itself. Trump’s campaign against ‘race ideology’ is thus not backlash – it is blueprint.

Under apartheid, museums helped naturalise domination. In postapartheid South Africa, when they failed to deliver structural change, they became sites of disaffection. In Trump’s America, they are being seized to restore a mythic national past, one where power does not need to explain itself. The lesson is not that museums must retreat into objectivity – objectivity was always a fiction. If institutions built on symbolic gestures without structural backing can be so easily captured, the answer is not to defend the symbols harder. Rather, it is to go further than they ever dared – to remake these spaces in ways that resist nostalgia, confront inequality and refuse to forget. Because history, once erased, does not return. And what is remembered defines who we can still become.

William Shoki is the editor-in-chief of Africa Is a Country. He lives in Cape Town