The myth of food being the cause for characteristic traits is extended in politics and popular culture, and that’s why you might sometimes need to lie about it

Annapoorani: The Goddess of Food (2023) is, at best, a mediocre Tamil film, the main selling point for which is lead actor Nayanthara, also called ‘Lady Superstar’ for her popularity and ability to deliver hit films in an industry otherwise dependent on the bankability of its male leads. In the film (which was cleared by the Central Board of Film Certification and first given a theatrical release before it began streaming on Netflix), Nayanthara plays the daughter of a devout Hindu temple cook who indulges his child’s love for cooking. Chasing her dream of becoming a world-class chef, she defies her parents and secretly joins a culinary school, where she must learn to cook and eat meat if she wants to pass: something her strict vegetarian upbringing forbids her from doing. Following her heart, and after a pep talk by a male Muslim friend who quotes an ancient Sanskrit verse about the god Rama eating meat, she begins to cook with meat. What follows is a predictable tussle between caste traditions and personal ambitions.

Though the film ran in theatres without any trouble, members of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), a hardline organisation, filed a case against the filmmakers for ‘hurting Hindu sentiments’ a few weeks after it began streaming. A catchall phrase without a clearly defined definition, the charge has been frequently used to censor any creative production that does not adhere to the narrow vision of what is acceptable for Hindu ultranationalist forces like the VHP, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and others under the Sangh Parivar umbrella. While Nayanthara and the film crew were forced to issue an apology, Netflix chose to be safer and removed the film from its platform. Sentiments were supposedly hurt because a Muslim was quoting in Sanskrit – a language viewed as holy and thus to be used only by caste Hindus, never by minorities – to say that gods in mythological India ate meat, and this influenced a Hindu Brahmin girl to defy the culinary traditions with which she had been raised. The issue touched many of the Hindu right’s favourite issues with minorities in general and Muslims in particular, including an insinuation of ‘love jihad’ (as a Muslim male character had befriended a Brahmin girl), and the larger, perennial debate between vegetarian and non-vegetarian diets in India.

The question of what people choose to eat has always been a can of worms in India, rife with complicated rules of caste traditions and socio-economic status. Rightwing politicians and fundamentalists – there is little difference between the two these days – dip into the can every now and then, manufacturing issues and keeping the embers of othering alive. The ban on beef consumption across most of the country might be old news, even if people continue to be lynched on suspicion of transporting cattle, but in the last few months alone, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led state governments have issued numerous orders disfavouring meat eaters.

A very incomplete list: eggs, fish and meat are no longer allowed to be sold in the open in Madhya Pradesh; a ban on the sale of meat during most Hindu festivals in most states – notably, minority communities are predominantly employed in the meat industry; eggs are not to be included in midday meals in schools if 40 percent of students vote against it. Eggs are considered nonvegetarian in India; whether to include them in midday meal schemes that benefit economically disadvantaged children – in many cases, this meal is the only one they might eat in a day – has been a contentious issue for years, sparked by charities like the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON)-run Akshaya Patra Foundation, which insists that eggs not be included in the millions of meals it serves to students every day across the country.

Weaponising food may be part of the well-tested processes used to other minorities. At a deeper level, though, the language of food politics in India reiterates processes of social conditioning that may not be new, but are increasingly now in the open, and enthusiastically propounded by those in government. And language, we must remember, matters. A vegetarian, who is almost always upper caste, is seen as pure, superior, mild and good, the ideal to aspire towards. If one was not born in a Brahmin community, the next best thing was to choose to partially, or fully, give up meat, a choice that is often celebrated as a morally right achievement. In everyday practice, some Hindus refrain from eating meat on certain days of the week and during some festivals, as per elaborate rules governing foodways, few of which have any basis in either science or scripture. On the other hand, a nonvegetarian is everything a vegetarian is not. This myth of food being the cause for characteristic traits is extended in popular culture, where Muslim invaders in period films and villains in nationalistic films are often shown devouring chunks of meat to depict their savagery.

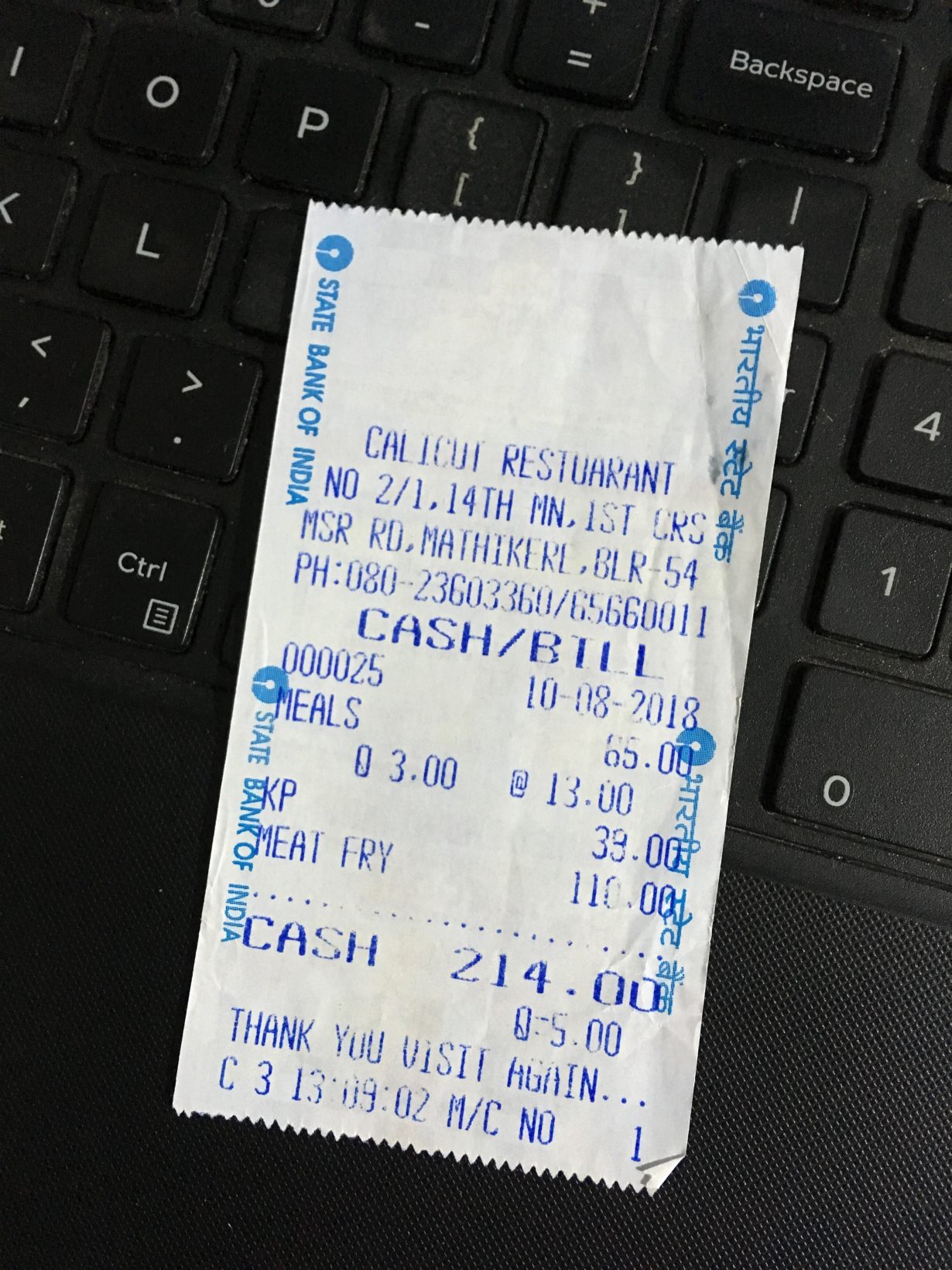

But it must be noted that though a vast majority of Indians are meat eaters, the very word ‘meat’ is rarely found in public spaces, save for butcher shops – though these too are often ghettoised, and kept far from town centres. Restaurant signboards might mention either ‘pure veg’ or ‘veg and non-veg’, ensuring that caste Hindus are warned against accidentally being polluted by eating in places that also serve meat. In Kerala-style restaurants established outside the state where beef is served, the word is kept off menus. At times the word ‘pothu’, meaning meat but understood as beef, may be written on a specials board in Malayalam. Euphemisms in bills might term it ‘meat fry’ or ‘meat curry’, in a bid to keep those who sell, cook and eat beef safe, and alive.

Such erasures help keep the supposedly offending food choices of millions out of public spaces, though not public consumption. This in turn changes a place’s visual language: what is left out and what it is replaced with. It is also an editing of what makes a good Hindu in today’s India: one who is vegetarian, god-fearing, yet hypermasculine and ready to defend the motherland – with weapons, if need be. In other words, a Brahminical lifestyle superimposed on the physicality of a Kshatriya warrior. Something both as personal and private as food, when used by state policies with the sole intention of driving communities further apart, is far more effective and longer-lasting than other overt measures. Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his ardent fans rooting for his party’s vision of a Rama Rajya (a perfect Hindutva-led country) know this only too well.

Deepa Bhasthi is a writer based in Kodagu